Forget fish and seafood – algae and seaweed is where the action is at, as Peter Ranscombe pulls on his waders to discover.

Think sea, think fish – vessels registered in Scotland landed 473,000 tonnes of fish and shellfish last year, worth some £542 million.

Species such as mackerel, monkfish, haddock and cod continue to be the most valuable to the Scottish fleet, alongside high demand for langoustine.

Meanwhile, exports of salmon leapt to £614m last year.

A new harvest is growing

Yet, away from the familiar fish and seafood that make their ways onto our plates, there’s a quiet revolution going on under the surface.

Entrepreneurs are turning their attention to other bounties that can be harvested from Scotland’s seashore.

Among them is Fiona Houston, whose Mara Seaweed brand was launched in 2013, and which is now stocked at shops ranging from House of Bruar and Loch Leven’s Larder through to national retailers such as Tesco.

Mara harvests seaweed from the shores along the East Neuk in Fife and from the growing number of seaweed farms around Oban on the west coast.

Seaweed farming at ‘tipping point’

Last month, Ms Houston applied for planning permission to open her own seaweed farm in St Andrews Bay.

Seaweed farms follow similar grid patterns to the more familiar mussel farms, with the big brown kelp seaweeds grown on ropes.

Ms Houston’s also fitting out her new factory in Glenrothes in Fife, which will be four times larger than her original facility in Edinburgh.

Mara already employs 10 people and Ms Houston aims for that figure to hit 50 within the next five years.

It’s not just her own company that’s growing, but the wider seaweed sector.

“As an industry, I think we’re pretty much at a tipping point,” explained Ms Houston.

“If we scale-up the processing facilities and the farms to ensure a quality supply, then we can start really going after export markets – there are exciting times ahead.”

‘Every single day, there seems to be a new use for seaweed’

Her enthusiasm is shared by Rhianna Rees, the coordinator at the Seaweed Academy in Dunstaffnage, near Oban, which was launched officially at the end of April.

The training facility is designed to harness the decades of seaweed expertise within the Scottish Association for Marine Science (Sams), an independent research institute.

The academy – which is the UK’s first dedicated seaweed industry facility – received a £407,000 grant in November from the UK Government’s Community Renewal Fund.

Two pilot courses have already been run for the local community, along with a bespoke course for Aberdeenshire Council.

Around 100 people a year are predicted to pass through the academy, which will run one-day introductory sessions and week-long intensive courses, along with practical sessions at two commercial-scale research seaweed farms operated by Sams.

Participants on the courses are expected to include people from other aquaculture businesses – such as fish farms – that want to diversify, along with landowners with shorelines.

“That’s what’s so exciting about this sector – we have such a broad range of people who are really excited and interested, from investors to processors to people like fishermen who don’t have as many fish stocks as they used to and are looking for alternatives,” said Ms Rees.

The broad range of people interested in the sector stems from the wide variety of applications for seaweed.

As well as using it as a food, it can also be turned into animal feeds, fertilisers, medicines, and even alternatives to plastic.

“Every single day, there seems to be a new use for seaweed,” Ms Rees pointed out.

“So many companies have come out with all sorts of different ways to use it as a material, from the lining for boxes through to ketchup sachets made from seaweed.”

In addition to its use as a food and material, seaweed also absorbs carbon and nitrogen while it’s growing, helping to combat climate change.

Industry growing like a weed

While the economic potential for seaweed may be dwarfed by traditional fishing and aquaculture – a Scottish Government research paper published in February suggested the industry’s turnover could grow from £4m at present to £71m in 2040 under its “higher growth” scenario – the jobs it creates are often on the islands or in remote rural areas.

“Coastal communities really need that economic impact and that boost and potentially something to bring that provenance back to the community,” added Ms Rees.

“Scotland is perfect for its provenance – you’ve heard of Scotch whisky and Scottish salmon, and now’s the time for Scottish seaweed.”

Away from seaweed, one company has been inspired by another marine resource.

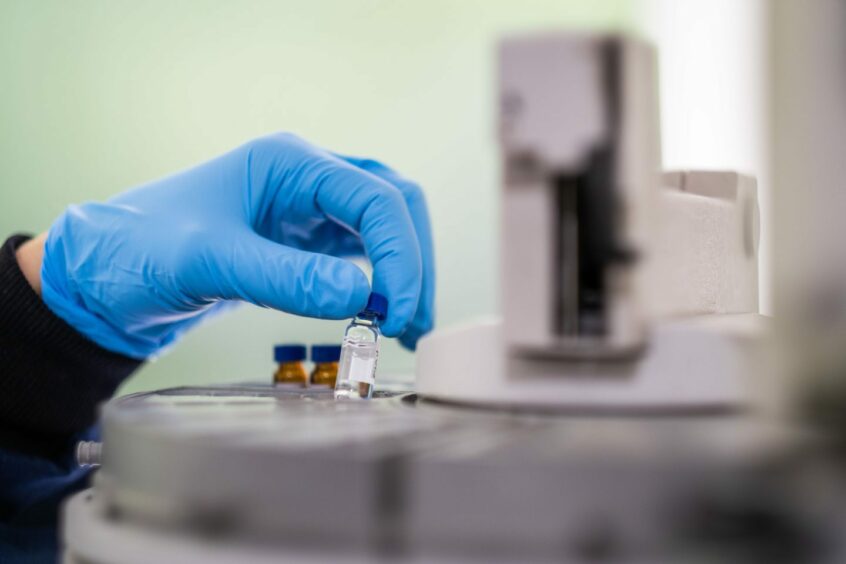

Edinburgh-based MiAlgae is taking leftovers including “pot ale” and “spent lees” from the first and second distillations at whisky distilleries and feeding them to a special type of algae, which then produces omega-3 oils.

The company already has around 23 members of staff and expects to double its headcount within a year, recruiting more production and research workers.

It currently operates a demonstration plant near Glasgow but could eventually build smaller facilities at rural whisky distilleries, in effect cleaning the nutrients from their pot ale and spent lees and then returning clean water to them.

Cutting out the nutrition ‘middleman’

Material from urban distilleries – which tend to have less space for on-site equipment – is likely to be collected and processed at a central hub.

Traditionally, pot ale was turned into a syrup and then spread on fields, while spent lees or grains – often called “draff” – were fed to livestock by farmers.

Nowadays, they are often combined into distillers’ dark grains and fed to cattle, or fed into an anaerobic digester, in which bacteria turn them into biogas, which can be burned instead of North Sea gas to produce heat or power.

“We’re offering another option for distilleries,” said Julian Pietrzyk, head of technical development at MiAlgae.

Following six years of research and development, the company is on course to make its first commercial sales before the end of this year.

Its initial customers are expected to be pet food producers, which currently use ground-up fish to add omega-3 oils to their products.

Eventually, MiAlgae aims to sell its products to fish farms, which also currently feed their salmon on “fishmeal”, or ground-up fish.

“Salmon are full of omega-3 oils for a reason – because they eat algae in the wild,” explained Mr Pietrzyk.

“When you are farming fish in any kind of aquaculture setting, the feed is actually just mashed up fish – it’s off-catch from other fishery industries.

“Farmed salmon get their oils from other fish, which have got their oils from algae.

“The idea for us was really just to cut out that middleman and grow the algae and feed it directly to the salmon.”

Conversation