Three Highland mums share their stories of baby loss – and new hope.

Losing a child is every parent’s worst nightmare. It’s a pain that many of us can’t even bear to imagine. Yet, for the three women courageously sharing their story today, grief is part of their lives.

Today is National Bereaved Parents Day and the theme for this year is ‘remember me’. Families are invited to light a candle to honour a lost life, but as Louise, Catriona and Susan explain, healing is more than ritual.

It’s breaking taboos. Supporting other families. Fundraising. Awareness raising. Most importantly – it’s saying their name.

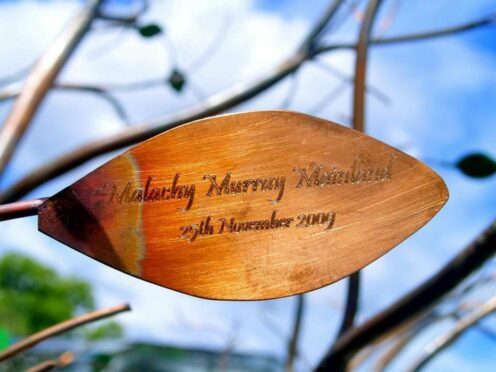

Louise Mainland explains: “How do I connect with my son now he’s not here? I do it by raising awareness. That’s Malachy’s legacy. It’s important for parents to find their voice, and a way to process their loss.”

Louise’s story

When Louise fells pregnant with her first baby in 2009, it started out as a “normal, happy pregnancy”.

However, Louise’s front waters broke at 20 weeks and she spent a couple of weeks in hospital for observation. At 29 weeks, she developed an infection and was taken in for an emergency C-section. Louise recalls getting a quick glimpse of her son’s eyes as he was whisked away to the Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU) in Raigmore Hospital, Inverness.

Sadly, after four hours, the paediatrician told Louise and husband Willie there was nothing he could do to save Malachy. He had a condition called amniotic band syndrome, which had caused development abnormalities.

“We went to SCBU and we were able to be with him, and bring family members in to see him and hold him,” says Louise. “He took his last breath in my arms.”

The hours and days that followed were a blur. “I was in complete denial,” says Louise. “He was my first baby.”

Thankfully, the team at Raigmore understood how important it is to capture memories of babies who have died. The medical photography team took photos of Malachy and midwives took hair locks and hand prints.

Louise says some parents don’t think they want this at the time, but the hospital take them anyway, just in case. Many parents are glad of these keepsakes later, when the initial shock has passed.

Louise keeps her memories of Malachy in a special box her mum bought for her. Because Willie and Louise knew Malachy would likely be premature, they had bought tiny baby clothes, and Willie took comfort in assuming the dad role – washing and dressing their son for his burial.

Malachy’s legacy

It’s a heartbreaking story, but Louise has found strength in new life.

“I’m very lucky that I had three children after,” she says. Their daughter Mia is now 11, and sons Malki and Murray are nine and seven.

“I held onto them when they were babies and didn’t want to let them go,” says Louise. “I gave everything to them.”

Though Malachy was only alive for six hours, he’s changed the family’s lives forever.

“I was the girl growing up wanting to be an accountant,” says Louise. “I wanted the big car and the fancy holidays. But when Malachy died, trying to figure out what life’s about, it made me reassess everything.”

Louise trained as a support facilitator with the child bereavement charity SiMBA, and went on to work for the child bereavement service Crocus, part of Highland Hospice.

She has canoed the Great Glen and climbed Ben Lomond to raise money for SiMBA.

Today, she says she’s not wealthy but she knows what’s important in life. “Malachy has a lot to answer for,” she says.

‘I hadn’t even said his name’

Indeed, Malachy touched other lives too. Catriona Gray remembers attending a SiMBA support group and hearing Louise talk about Malachy.

“It wasn’t long after my own son had died, and it changed everything for me,” says Catriona. “I’ll be forever indebted to Louise and her mum Norma for that day. Prior to that meeting, I hadn’t spoken about Charlie, or even really said his name. I heard Louise talk about Malachy and it blew me away.”

Catriona was still reeling from the loss of her baby boy, Charlie, and recalls: “I didn’t know I was allowed to speak about him. It was like I suddenly had permission to be Charlie’s mum.”

One of the hardest things about child bereavement is that it’s still shrouded in mystery. People are uncomfortable addressing it, and don’t know how to help.

Sadly, stillbirth and miscarriage can be particularly hard. Charlie’s heart stopped beating when Catriona was 20 weeks pregnant. To this day, she doesn’t know why it happened. Catriona had lost a baby before, but this had seemed like a very routine pregnancy.

A death certificate, but no birth certificate

Babies who die before birth don’t get a birth certificate unless they were born after 24 weeks, so Catriona and husband Andy found themselves registering his death, but not the fact that he was ever born.

In their case, it was baptism that gave them some peace.

“When Charlie was born I was asked if I wanted to see the hospital chaplain,” says Catriona. “I couldn’t find the words to ask if I was allowed to have him baptised. I was scared they’d say no, that’s he’s not a person.

“Then I was speaking to one of the chaplaincy team and she offered it. It meant so much to me. It was just beautiful.”

Catriona has three living children – Hamish, 10, Millie, 9 and Tommy, 3. Tommy was born after the family lost Charlie, and like his big brother, he was baptised at the Raigmore chaplaincy.

Catriona says Charlie remains one of the family. “He’s part of our everyday lives,” she says. “The love they feel, they link all that back to their brother. We make a cake on his birthday, and grow things in the garden to celebrate him. We call those our magical moments.”

A new perspective on grief

This year’s end-of-term celebrations were particularly hard for Catriona, a school teacher, as Charlie would have started P1 after the holidays.

Catriona remembers wondering at Charlie’s funeral when the pain would end. In time, she realised it never would, but that’s okay.

“I made my peace with the fact that I will grieve him forever, but not in a morbid way,” she says. “It was a shift in my mind from trying to get back to who I was before, to realising this is who I am now. I’m Charlie’s mum.”

Like Louise, Catriona has photos from her short time with Charlie and memories to hold onto. She recalls singing songs with him and standing at the window looking at the stars together.

The hospital has a ‘cuddle cot‘ which keeps babies cool, allowing families to have more time with them after they have died.

Medical approaches to child bereavement have come on a long way in recent years, helped by charities like SiMBA.

‘You take comfort where you can’

Unfortunately, this wasn’t always the case. Susan Simpson lost two babies to miscarriage, Alex in 2007 (at 13 weeks) and Eilidh Beth in 2010, at 32 weeks.

Susan experienced great discomfort late in her pregnancy with Eilidh Beth, and a scan at 32 weeks showed the baby was very unwell. She had a condition called non-immune hydrops fetalis (NIHF), a severe condition linked to Down’s Syndrome.

Susan was booked for an emergency section, but tragically, her daughter died the night before. Susan went on to develop a fever which meant the section had to be done under general anaesthetic. She believes that’s how it was meant to be.

“If it was a regular section I’d have been awake and my husband would have been in with me – we’d have been completely devastated,” she says. “I believe our wee girl was looking out for us. You take comfort where you can.”

In 2010 there were no cuddle cots, so Susan only got a couple of hours with Eilidh Beth. To this day she wishes her daughters Charis (then five) and Niamh (then two) had the chance to meet their sister.

“I wish someone had told me then how much it would help them with their grief,” she says. “That’s why I’m so passionate about child bereavement care now.”

Breaking the taboo around child bereavement

Susan has set up her own charity to support other grieving parents.

“If you have that precious time and you can have your family in to meet the baby, the baby becomes real in people’s lives,” she says.

Susan recalls an incident in Tesco not long after she had Eilidh Beth. A man she knew stopped to offer his condolences, and little Charis said ‘My baby sister died’. The man was utterly taken aback.

“Infant death is still such a taboo subject,” says Susan. “When we lose an older relative, everyone talks about them and shares memories of them. The short time we have with our babies is all we have of their lives. We have to be able to talk about them.”

Catriona and Louise agree. Louise speaks of feeling all that love and loss, and realising she doesn’t need to hold it in.

Sharing their stories – with other parents and beyond, as they do here – is a release and a comfort. That’s what struck Catriona when she first said Charlie’s name at Louise’s support group.

“I realised that Charlie died but I haven’t lost him. I got him back.”

If you have experienced child loss, the Scottish Government website includes links to useful information and support.

More from the Schools and Family team

‘Love is always the right approach’: Island teacher urges MSPs to make inclusivity a priority

Kept in the dark: Council refuses demands to inform parents of ‘abusive and degrading’ messages

Conversation