“If you are walking alone at night – especially if you are female – don’t” – was the shocking warning given to the women of Aberdeen in 1979.

This sinister safety message was part of a poster campaign devised by the student representative council and the police, after a young woman was seriously assaulted.

The safety plea came amid a backdrop of fear: in Yorkshire, a serial killer was targeting lone women after dark. Nine women were dead, many others had been attacked and police were no closer to catching a perpetrator.

It would be another two years before Peter Sutcliffe, dubbed the Yorkshire Ripper, was convicted for his heinous crimes against women.

Meanwhile, the collective mood was bleak, it was February 1979 and Britain was barely dragging itself out of the frigid Winter of Discontent.

Blondie topped the charts with Heart of Glass and feminist frontwoman, the progressive, punky Debbie Harry, was pushing the boundaries of women in music.

But the message for women during the cold, grey, winter nights of Aberdeen was clear: stay at home.

Reclaim the night

Between 1974 and 1978, the reporting of rapes in Aberdeen increased from four to 12.

And in 1979, self-defence classes were offered at the University of Aberdeen following a number of assaults on female students in the previous months.

But, unhappy that the onus was put on victims to protect themselves, rather preventing the wrong-doer, a group of women decided to take action.

‘Help to reclaim the night’ was the rallying call urgently relayed to the frightened women of Aberdeen, in the Evening Express.

A powerful piece of editorial by woman’s editor Jennifer Simon explained how women in the city were too scared to even go to evening classes alone.

And that “fear of being the victim of a sexual assault is one that women have to live with”.

Keys around her knuckles

One woman in her early twenties shared her own experiences of walking home after dark.

She said: “I’ve been subjected to verbal abuse.

“I’ve never been physically attacked.

“Now every time I go out I think ‘will this be the first time’?”

The young woman explained how she would walk home to her flat in east Aberdeen with her keys wrapped around her knuckles.

It was a story echoed by women across the city, and indeed the country.

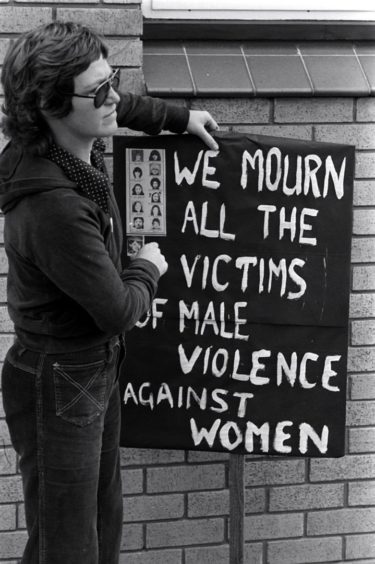

In 1977, Al Garthwaite organised the UK’s first Reclaim the Night march in Leeds as part of Leeds Revolutionary Feminist Group. Raising concerns about violence towards women and the Yorkshire Ripper, the movement inspired several more.

In Scotland, they took place in Glasgow and Edinburgh, before the Aberdeen organising committee encouraged women to take a stand in the Granite City in 1979.

Fight for rights

The rallying call rang out in black and white on newsprint: “What kind of a society do we live in when women haven’t the freedom to move around as they please?

“Is it the kind we want to keep – or the kind we want to change?

“Most women experience some form of sexual harassment in their lives, whether it be wolf whistles, offensive remarks, being followed, physical intimidation, or rape.

“It happens anywhere, every day, and is a threat to every woman… a threat which becomes more sinister as darkness falls.

“Does it make you stay in when you want to go out? Do you shut the windows and lock the doors if you’re at home alone?

“Do you feel uneasy waiting for a friend in a public place?

“… Don’t you have the right to come and go as you please?”

The campaigners also sought to dispel myths around sexual harassment; to emphasise that what a woman wears, drinks or how she acts does not mean she is inviting unwanted attention.

Women who shared the belief and wanted to fight for the right to walk the familiar streets of their home city, were urged to join the march.

Wielding torches

Starting at the university’s Hillhead halls of residence, the route took marchers down Don Street, King Street, Nelson Street, Gerrard Street, Mounthooly, Hutcheon Street, George Street and Union Street to the Music Hall.

But ironically, the university had to arrange transport to ensure the women got back to their halls safely afterwards.

In addition to its poster campaign, the student representative association called for better lights, roads and transport, but said “in the long-term the problem must be tackled too by a change in society’s attitude towards women”.

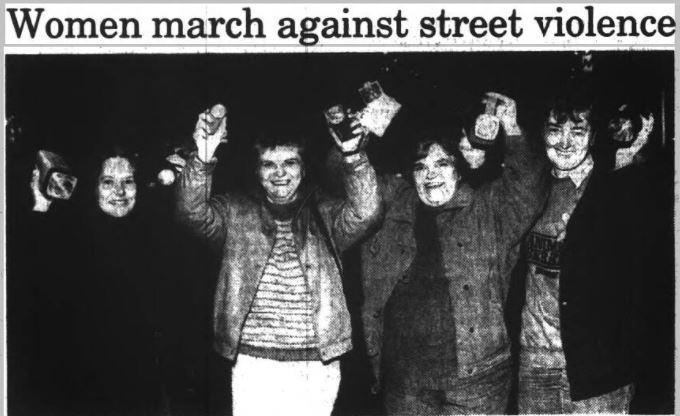

But, by the late 1980s, women in the city still felt vulnerable and another march was organised in response to “an escalation of violence”.

Wielding torches, dozens of women illuminated and reclaimed the streets from darkness and danger for one night only, on March 11 1988, making front page news.

Speaking after the protest, one of the organisers Jane McMillan said: “The purpose of the demonstration was to emphasise how women are feeling about violence on our streets.

“I do think it is getting worse in Aberdeen. But the problem is not only in Aberdeen – it is throughout Britain.”

A Grampian Police spokesman at the time acknowledged that “society in general has become more violent” but added “we do not accept that Aberdeen is in any way exceptional in comparison with other cities”.

Grief and outrage

But 42 years on from the first ‘Reclaim the Night’ campaign, the language and pleas sound disappointingly familiar.

Women are once again stepping out after dark, this time to ‘Reclaim These Streets’ following the tragic death of Sarah Everard in London earlier this month.

The 33-year-old was walking home on familiar roads around Clapham Common after visiting a friend, when she vanished on March 3.

Her body was found a week later, and a police officer has since been charged with kidnapping and killing Everard.

Across the UK, women – and men – are challenging attitudes towards women’s safety, while paying silent tributes at vigils, including one at Aberdeen’s Castlegate.

In scenes across the country, uncannily similar to those of the 1970s and 80s, there has been an outpouring of grief and outrage by women told to stay at home to remain safe.

The messages of fear and anger in the Evening Express in 1979 could so easily have been emblazoned upon the banners of protesters in London.

History repeating itself

Professor of communication and media at Robert Gordon university, Sarah Pedersen, said “nothing has really changed” in the last 42 years.

Prof Pedersen, who is also on the board of directors of Grampian Women’s Aid, added: “I’ve been making the same connections with my students.

“We started the semester by talking about the Yorkshire Ripper and the way in which the police told women to stay in their houses. When we talked about it in January the students were saying ‘things have changed now’.

“But no, last week we had police telling women to stay in their houses to keep safe, so nothing has changed at all, which is a sad indictment of society in general.

“It’s this repeated message, we’re back saying the same things over and over again, which is what is so frustrating that nothing seems to have changed.”

Pressing for change

Many women have taken to social media to share their own experiences of sexual harassment. This virtual support network reflects a similar movement during the 1970s.

Prof Pedersen said: “In the 1970s, what we now call second-wave feminists, had this idea of ‘consciousness-raising’.

“This was when women met together in their own homes and shared stories of what had happened to them as a consequence of their sex, the abuse they received on a daily basis – the sorts of things we’ve been hearing today on social media.”

But, the language used to describe victims is as much a problem now as it was in 1979.

Prof Pedersen added: “The way we ought to be framing conversation is ‘men have attacked women’, ‘men have murdered women’, the onus should be on the perpetrators, not on the victims.

“We’re wasting so much time in our heads worrying and thinking about how to keep ourselves safe, that men just don’t do. It’s disappointing, but what’s important is that we need to use this moment to press for change.

“We need to use this as a launching pad to press politicians and police for actions and change.”

Taking action

Despite the lack of change in society’s attitudes, by taking to the streets of Aberdeen in the 1970s, these brave women laid the foundations that continue to help women today.

Meanwhile, new debates around women’s safety can galvanise people to take action.

Prof Pedersen added: “Women did a lot of work 40-50 years ago setting up places like Women’s Aid and Rape Crisis and all of those other wonderful organisations continue to help women.

“There has been some change and I think that media is more likely now to feature or centre women’s voices around these issues. It’s important politicians are discussing it, there have been changes, but what hasn’t changed is we still have the problem.”

This is a sentiment echoed by Fiona Rennie, Aberdeen Women’s Alliance convener, she said: “It is great the awareness is out there just now, with the lighter nights coming in and, at this time, nothing open late in the evenings.

“But will the interest and awareness still be there when we are back to normality and women are walking the streets in fear?”