From nomadic student to business owner, master craftsman and glassblower Brodie Nairn now shares the top table with global industry names, from supercar manufacturers to vintage whisky brands.

Working with corporate teams, Brodie, 48, takes glass design to another level by creating one-off, bespoke art pieces that embody the commercial creative vision of his high-end clients.

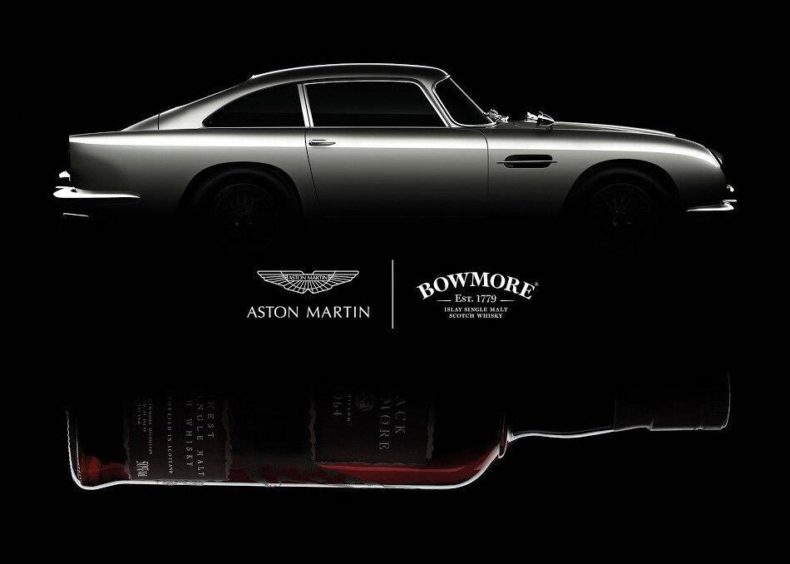

Even during lockdown, demand for Brodie’s skills remained high. His clients include big names such as The Savoy, Bowmore, Glenfiddich, Macallan and none other than motoring manufacturing legends, Aston Martin.

It’s a long way from his art school graduate days where he travelled the globe seeking out contemporary glass design experts, innovators and artists to help him hone his craft. Today he works with Nichola Burns (“the love of my life”), balancing business and family life, and in 2005, they took the plunge and opened Glasstorm in Tain.

Drumnadrochit-born Brodie and Nichola’s glass journey started in the early ’90s when they both met at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen, but Brodie’s love of glass began with a summer job at a glass studio in Drumnadrochit.

“By the end of summer I realised I was working with the wrong material,” he said. “I fell head over heels with glass and that discovery led us to go on to pursue glass as a material to work with.”

The couple ended up at a specialist glass school in the West Midlands and then devoted the next decade to travelling around the world working a year or two with each studio, factory or artist, Nichola starting with world-famous artist Alex Tuzinky straight from college, with Brodie’s route more circuitous approaching artists by mail and without the benefit of an online portfolio.

“This is before the days of the internet,” he reminds. “We actually wrote to people. You’d send it in the post and wait two weeks for it to get there, and then someone might write back.”

This pedigree of time and patience is now written into Brodie and Nichola’s work, with many clients looking at long-term projects – none more distinct than the slow process of maturing whisky.

“Many of these clients will say, ‘This product is going to come good in three years. Let’s do all the designing now and get ready for when it turns 50’. There are very few industries that can do that,” says Brodie.

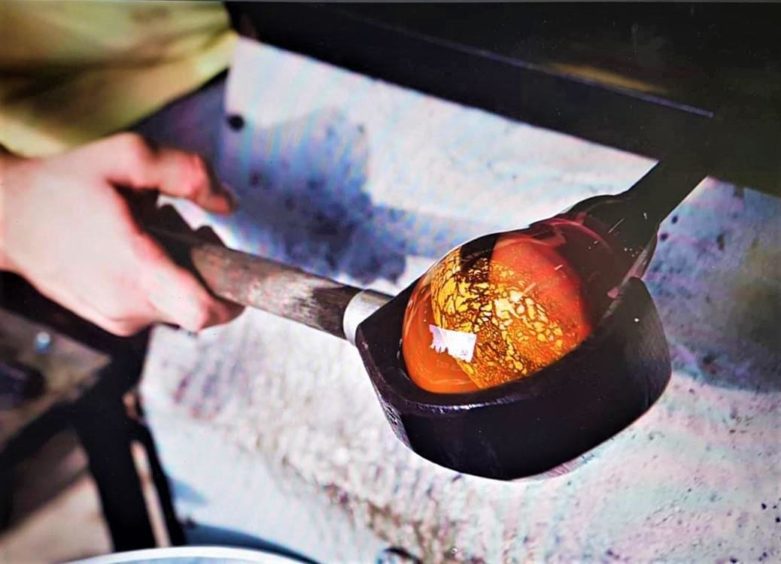

The process of blowing glass is as painstaking and technical as that of the master distiller, with each piece being worked over and over until perfection is reached, requiring hand-to-eye skills and both hands working in perfect co-ordination.

It is this pursuit of perfection that brought Brodie and Nichola’s work to the attention of the likes of Aston Martin and Bowmore, the Bowmore bottle taking a particular place of pride. Here, Brodie used platinum, a material, he says, that had not been used in molten glass before.

“We’ve worked with Bowmore for over a decade now,” he says, adding that the Islay company gave them a blank sheet of paper for the design of its 54-year-old whisky bottle.

“We thought of the stories of the Number One Vault where the most expensive whiskies are stored,” he said. “The Number One Vault faces right out into the Atlantic, the sea literally crashes against the side of the warehouse door, and so we thought, how cool would it be to have a crashing wave right around the bottle?”

The team got to work and decided to incorporate platinum into the glass wave.

“If you look closely at those waves they have a shimmer that is like the shimmer of light that is the crashing waves that you see on the sea,” says Brodie. “It looks really spectacular.”

The stopper and collar was made by Hamilton & Inches (silversmiths to the Queen), with the bottle and whisky combined fetching as much as £363,000 at Sotheby’s. Even without the whisky, the bottle remains truly unique.

“Yes, you don’t take it down and chuck it into local recycling,” laughs Brodie. “But to be the creator of that bottle, for our name, a Highland company to be up there in the top Google search, is a fantastic place,” he says. “We’ve arrived.”

Aston Martin also graces Brodie and Nichola’s client list. In fact, in one collaboration, Brodie undertook the very technical and skilled task of incorporating a DB5 piston within the Black Bowmore whisky bottle to celebrate both brands’ big years: 1964 the year the distillery installed its first steam boiler, and the DB5 selected as the wheels of choice for James Bond’s Goldfinger.

The willingness to try new things and take artistic chances has meant continuous work for Glasstorm, even through Covid.

“It would be wrong of me so say there isn’t an element of risk but it’s a manageable risk because we’ve got the experience,” says Brodie, who refers to the work as being similar to ‘hand-made engineering’.

“We’ve got the know-how and we look at these projects with a can-do attitude, and therefore we make things happen. This allows us to have very exciting projects to come through our way.”

So what does the future hold for Glasstorm? Brodie won’t be drawn on the next big name on the list but says: “If you knew what I knew, next year is going to be absolutely bonkers. I’m very excited about what the future holds in terms of the projects that will be launched in the next two or three years.

“Right now we’re happy with where we are. To be sitting at the table with these brands and to be talked about in the same breath, we’re really proud of that.”

Blown glass

Blown glass expertise takes years to perfect and Brodie’s studio is full of equipment designed to help creative visions come to fruition. The furnace melts the glass inside a crucible then, through the glory hole, the glass blower inserts a steel pipe and gathers up a layer of molten glass.

This is then rolled on to a marver (steel surface) and the shaping process begins. The molten glass has to be kept in motion, which means plenty of movement back and forth between glory hole and marver.

For colour, frits and powders are melted in, and the glass is moved back once more to the bench where the shaping process takes place, using any number of items such as wood or stainless steel tools.

The blowing itself involves puffing into the pipe to create a bubble, followed by more heating, turning and shaping – a cycle that will be repeated several times until the desired shape is achieved.

The final piece will eventually move to an annealing oven which very slowly cools the glass over many hours to avoid thermal shock which will fracture the glass.