In the 1780s, terrible storms battered Scotland’s coastlines and countless ships and vessels were lost or wrecked by the wild North Sea. This saw a huge impetus to build lighthouses around the country, to help sailors’ navigation and alert them to land or treacherous rocks.

-

Some Press and Journal online content is funded by outside parties. The revenue from this helps to sustain our independent news gathering. You will always know if you are reading paid-for material as it will be clearly labelled as “Partnership” on the site and on social media channels.

This can take two different forms.

“Presented by”

This means the content has been paid for and produced by the named advertiser.

“In partnership with”

This means the content has been paid for and approved by the named advertiser but written and edited by our own commercial content team.

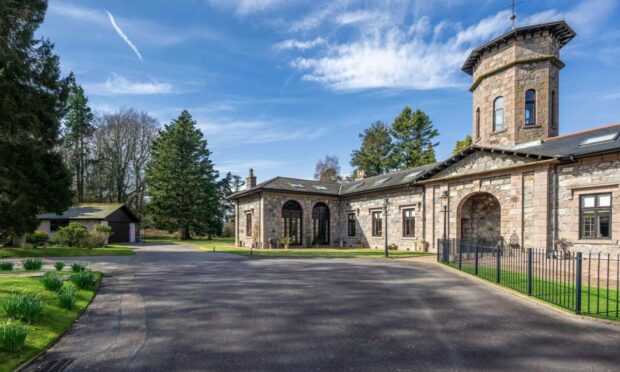

On the extreme North East coast of Scotland, Kinnaird Head provided the ideal location.

It is now a popular tourist attraction that sits alongside a museum re-telling its exciting history.

Before the Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB) was established in 1786, private lighthouses were built by landowners who required an Act of Parliament to receive lighting dues.

The land and castle at Kinnaird Head belonged to a cunning Lord Saltoun. Fed up of paying for the upkeep of the empty castle which lay on his property, Lord Saltoun had allowed it to fall into disrepair. But then he had an idea.

The original thinking behind Kinnaird Head Lighthouse

Michael Strachan, author and expert at Kinnaird Lighthouse Museum, says: “As the need for lighthouses became ever-more prominent, in 1785, Lord Saltoun sought to receive an Act of Parliament to build a private lighthouse on top of his castle by having friends spread word of the value of the land at Kinnaird Head.

“He declared it was the ideal setting for a light, sitting right at the mouth of the Moray Firth, visible for miles from the surrounding ocean.”

Unluckily for him, laws changed in 1786. Rather than legislating for private lighthouses, the Act of Parliament set up a lighthouse authority, the NLB, which would be responsible for all lights in Scotland.

“Kinnaird Head, Eilean Glas, Mull of Kintyre and North Ronaldsay were all named in the Act of Parliament as locations for the NLB’s first lights – Kinnaird Head’s inclusion being in no small part thanks to Saltoun’s friends doing his bidding in the Committees,” Strachan explains. “This was a blow for Lord Saltoun, who would receive no financial reward if the lighthouse was nationally run.”

The castle at Kinnaird Head

The NLB were keen to use the castle for the lighthouse, not only because of its position, but because of the general inexperience of the engineer, Thomas Smith.

A lamp maker who was born in Dundee and worked in Edinburgh, Smith had never built a lighthouse before, but got the job through his expertise and innovations in lighting technology. Because he didn’t know how to build a lighthouse tower, it made sense to use the one already structured on top of the old castle, just as Lord Saltoun had planned.

They removed the top section of the castle, fireproofed it with lead and built a timber lantern with panes of glass. The bright light was created from 17 of Smith’s parabolic reflectors, the invention of which essentially got him the job.

While it worked at the time, putting a light on top of an old building does not make the most professional looking lighthouse, and by the 1820s, Kinnaird Head was a bit of an embarrassment.

Strachan adds: “Compared to the likes of Bell Rock, perhaps the most famous lighthouse in Scotland located 12 miles off the coast of Arbroath, a timber lantern built on a crumbling castle didn’t really cut it.”

The work of Robert Stevenson

However, it was Thomas Smith’s involvement in lighting up lighthouses that inspired the famous work of his stepson, Robert Stevenson.

Formally trained and skilled as a lighthouse engineer, Stevenson visited all of the old lighthouses his stepfather had structured, and worked to bring them up to the national standard.

Stevenson’s original intention was to demolish the castle and build an entirely new tower, but famous writer and historian Walter Scott had said how nice it looked with the light above it, so Stevenson was persuaded to build a brand new lighthouse tower through the existing tower of the castle.

At Kinnaird Head, this meant building a whole new lighthouse – and it became Scotland’s very first.

Did you know you can visit this lighthouse, and it will look just how it was when the keepers were there? Kinnaird Head is the only operational lighthouse you can visit in Scotland!

The renovations took place between 1822 and 1823, but the light at Kinnaird Head always remained lit. Even when they replaced Thomas Smith’s old lanterns, Stevenson’s team used lamps from a lightship hoisted up on masts set on the castle roof.

“These were apparently the very same lamps used on the lightship which marked the Inchcape Reef in 1807-11, while the Bell Rock was being built,” says Strachan.

The light keeper at the time, therefore, would have had to work around stairways and holes through floors, ceilings and walls.

Who were the first light keepers of Kinnaird Head?

Between Thomas Smith’s and Robert Stevenson’s towers, from 1787 to 1823, there were two light keepers at Kinnaird Head. The first was a man named James Park, appointed by the NLB in 1787.

“Not a lot is known about Park, other than he was a ship owner prior to becoming a light keeper,” says Strachan. “He was already 70 years old when he started at Kinnaird Head, would have tended to the then 21 lanterns alone, and was paid a shilling a night.”

Light keepers at the time were required to have a second person living with them, but it is not known who lived with James Park. Indeed, he lived a quiet life.

When Park reached the age of 80, Robert Stevenson realised he was no longer able to continue with his duties, and he was given a modest pension of £5 annuity.

In 1797, Park was replaced by a man named George Gray, described in the Church Registers of Leith as a Sailor or Mariner, who lived at Kinnaird Head with his wife and children.

When Stevenson was doing his inspections in 1804, however, he noticed the work wasn’t being done to its usual standard.

The need for two light keepers

It came to light that Gray had taken ill and his wife was carrying out the light keeping duties, as well as taking care of her husband and their home.

“It was occasions such as this which led Stevenson to introduce the concept of assistant keepers,” says Strachan. “By 1815, Kinnaird Head had a principle keeper and an assistant.

“This also meant that Stevenson was more likely to know exactly what was going on at each station. In his words, ‘the keepers, agreeing ill, will keep each other to their work.’”

It was Gray who kept the light at Kinnaird Head when the new tower was being built, which meant he had to attempt to keep dust from the lanterns and his oil. His workload would have increased significantly as a result. However, the team did use second hand reflectors until 1824 to ensure any dust from construction would not damage the silver finish of the new reflectors ordered for the new lighthouse.

As well as a new tower, which was finished in 1823, there was an upgrade of technology, which meant new lamps and the Stevenson reflector.

If you visit The Museum of Scottish Lighthouses, you will be able to see the UK’s largest collection of lenses.

Gray, in his 70s by this point, was unable to work the new technology, so in 1824, Stevenson spoke to the commissioners of the NLB and fought for Gray to receive a healthy pension off the back of his loyal service.

This was a long time before state pensions. And, as light keepers lived and worked in a home provided for them by the NLB, when they were let go, they essentially had nothing.

This highlights Stevenson’s kind hearted nature and his paternal instincts towards his keepers. It is evidenced in letters that Stevenson and Gray thought highly of each other and had a strong friendship. George Gray even named his child Stevenson Gray, after the famous lighthouse engineer.

Today the job of a light keeper is no longer required, as all of Scotland’s lighthouses became automatic in the 1990s. Kinnaird Head Lighthouse was de-commissioned in 1991 and replaced with a purpose built automatic lighthouse. The very last lighthouse in Scotland was automated in 1998 at Fair Isle South.

The towers themselves remain as important as ever – did you know that you can climb them if you visit this amazing tourist attraction? As Scotland’s first mainland lighthouse, Kinnaird Head now boasts a story unlike any other.

Plan your visit to The Museum of Scottish Lighthouses

Find out more about the history of Kinnaird Head. Plan your visit now to The Museum of Scottish Lighthouses on Stevenson Road, Fraserburgh. You can have a tour of Kinnaird Head Castle, the lighthouse and lighthouse museum.