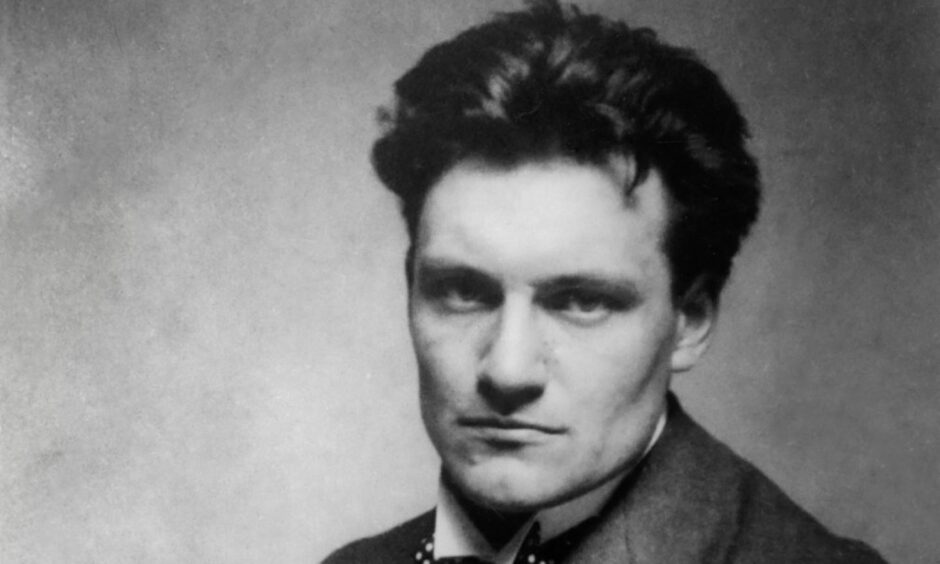

He was the man who emerged from humble origins in north-east Scotland to become an acknowledged heir to the likes of Whistler and Rembrandt.

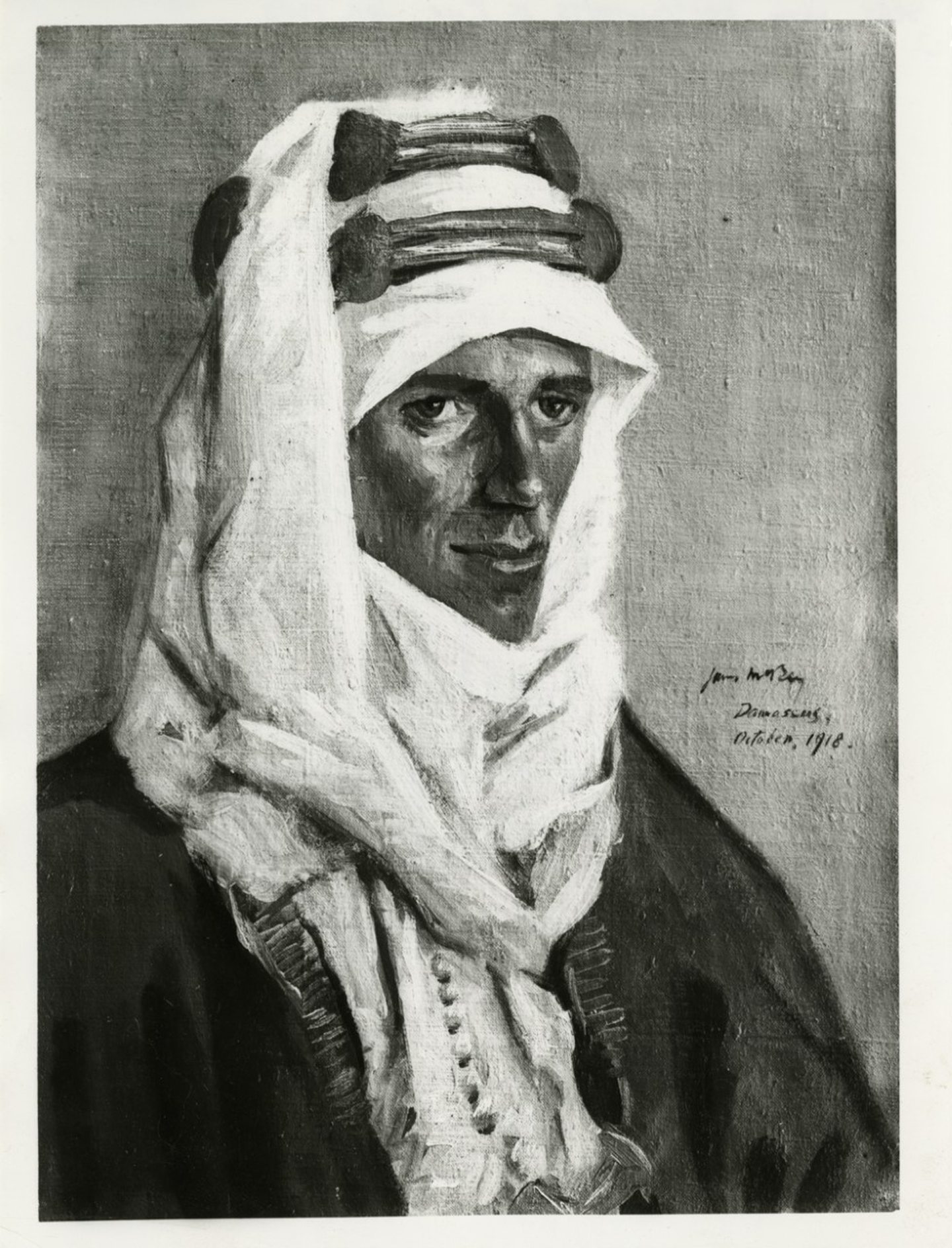

Yet, the chances are that if you are not an art expert, you won’t have heard of James McBey – creative genius, war artist, passionate lothario and adventurer in far-flung countries who produced one of the first and most striking portraits of Lawrence of Arabia which still hangs proudly in one of London’s grandest museums.

However, moves have been made to shine the spotlight afresh on this mercurial figure, who entered the world as the illegitimate son of a blacksmith’s daughter just two days before Christmas in Foveran in Aberdeenshire in 1883 – and whose subsequent exploits are the stuff of a Boy’s Own magazine story.

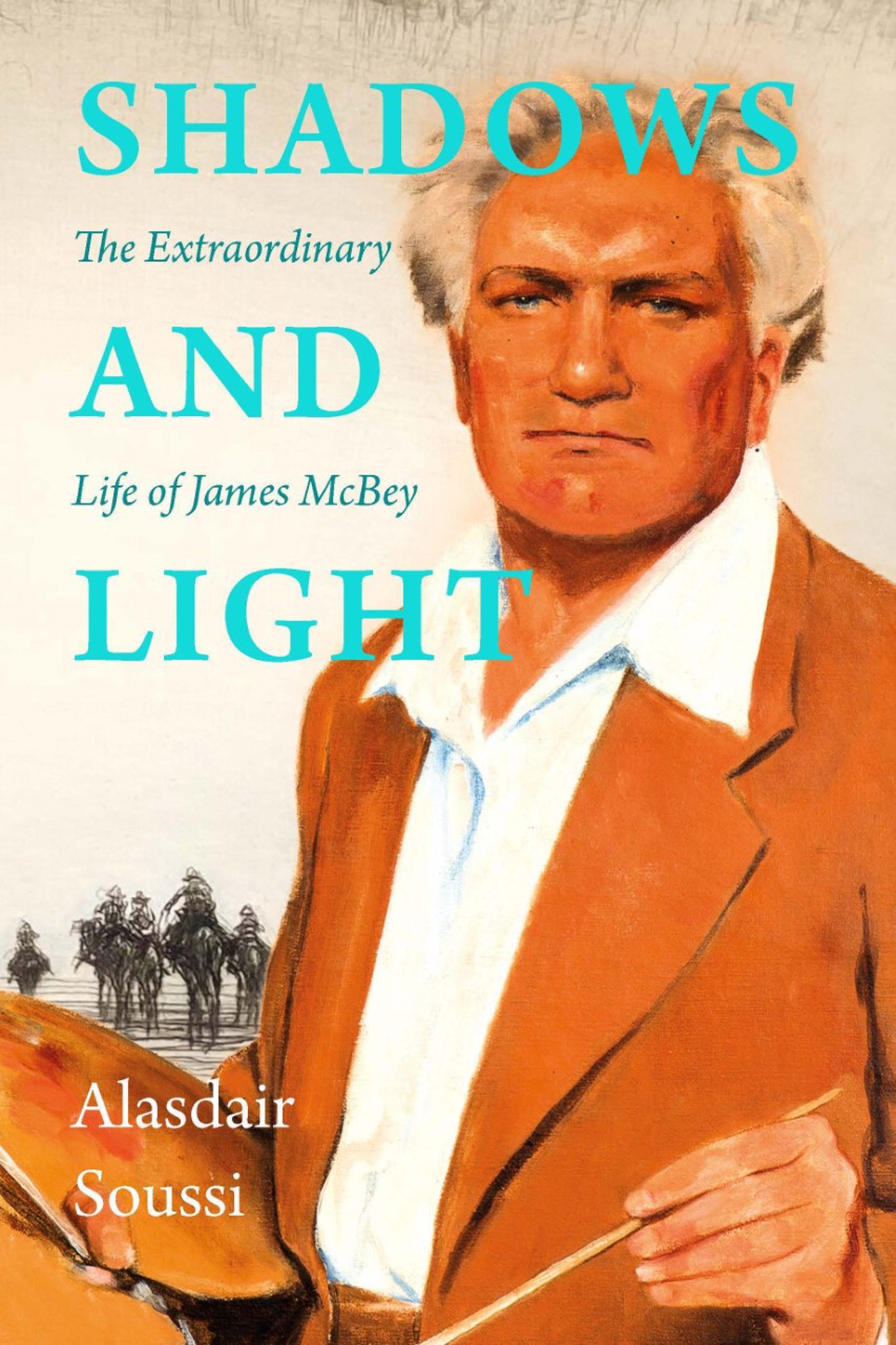

Author Alasdair Soussi has vividly conveyed the myriad strands in McBey’s life in his new biography Shadows and Light, which invites the reader into a magical and mesmerising critique of the man whose talents were employed during the Great War and thereafter in his beloved Morocco.

There’s no dearth of intrigue or romantic interest and Alasdair doesn’t pretend his subject was a saint.

But what a story and what an example of how somebody can come “squealing into the world at 4am in Aberdeenshire” and embark on such a storm-tossed journey.

‘I was fascinated by his work’

He told me: “A little over 10 years ago, I was writing an article on Lawrence of Arabia in my role as a journalist. I knew of the famous portrait of Lawrence hanging at the Imperial War Museum in London, but hadn’t thought much about who had painted it.

“I am not an art historian and so my interest in art was (and remains) that of an eager amateur until my eye caught the artist’s signature to the right of the picture: ‘James McBey, Damascus, October 1918’.

“I thought with a name like McBey he must be Scottish or Irish – and was astounded that a quick search on the internet revealed a Scottish artist who was not only a superstar etcher and painter on both sides of the Atlantic during the inter-war years especially, but one who lived a truly cinematic life.

“I was hooked from then on, but I couldn’t believe that there was no biography of him and that he wasn’t a name on everybody’s lips like other trailblazing Scots such as David Livingstone or Robert Burns.

“I was thrilled when Scotland Street Press in Edinburgh commissioned me to write the book in early 2020 – and am honoured to be here as McBey’s official biographer.

So many different facets to him

“My intention was to reveal the man behind the art and awake a sleeping giant of Scottish, British and European history. I discovered that McBey, born illegitimately in late Victorian Aberdeenshire, was seen as the etching heir to Rembrandt and Whistler, and that his role as official war artist in the Middle East during the Great War (where he painted Lawrence) was just one of many adventures he had.

“He was a great globe-trotter and womaniser, and even after he married a very beautiful American, Marguerite, in 1931, he continued his affairs.

“But he was very multi-layered, and was haunted by his past – his illegitimacy, his mother’s tragic suicide and so on. He is buried in Tangier, Morocco, a place he adored.”

His Scottish roots were precious to McBey, even if the region had melancholy associations, whether in the death of his mother or his dreary work as a bank clerk in Aberdeen. But, although he travelled the globe, and was captivated by different people and places, he never lost his lilting north-east accent and kept coming home.

Indeed, one suspects that he would be pleased to know that, however belatedly, his distinctive works are becoming the subject of an exhibition in the Granite City.

The Art Gallery was special to him

Alasdair said: “Aberdeen Art Gallery is the spiritual home of James McBey’s work. They host the biggest McBey archive in the world, so when I discovered that they wanted to hold an exhibition directly inspired by the book’s publication and named after the book and wanted me to curate it to boot, I was blown away.

“Right at the start of my discussions with the gallery about the exhibition, I remarked to them that I couldn’t believe they were going to dedicate a full day or a weekend to holding an event based on my book, so I was shocked to discover that the exhibition would in fact last for more than three months – from February 11 to May 28.

“It has been a real privilege working with the gallery to make this exhibition a reality.”

Alasdair has been a freelance journalist since graduating from Glasgow University in 2002. And, as somebody of Scots-Lebanese parentage, he has always had an interest in Scottish and Middle Eastern affairs, which explains why he has worked in a variety of Arabic-speaking cities such as Amman, Beirut and Cairo.

In that light, he fully understands McBey’s own ties to the Middle East, his role as official war artist in the region during the First World War and his life in Tangier.

There’s an empathy in these pages which provides the book with a compelling vim and vigour. The exhibition should be well worth a visit in the coming months.

Shadows and Light is published by Scotland Street Press.

Further information about the exhibition can be found at: www.aberdeencity.gov.uk/AAGM/plan-your-visit/aberdeen-art-gallery