The tale of how an Aberdeenshire polar explorer saved Britain’s Antarctic Empire in WWII is all but forgotten, until now…

It was one of the most secret missions of World War II, which has been forgotten for 70 years.

But now the full extraordinary story of a covert British expedition to Antarctica and the Scots explorer from Aberdeenshire who led it has been revealed for the first time.

At the height of World War II, Winston Churchill secretly dispatched a team of polar experts to the southernmost reaches of the earth.

Under the cover of a scientific expedition, the mission’s real aim was to establish a physical presence on territory claimed by Britain in the Antarctic – the ownership of which was disputed by several nations, including Argentina, Chile and the United States.

Argentina was the most forceful in pressing her claims in the region, sending an exploration vessel, the Primero de Mayo, to British Antarctic territory in 1942 and setting up meteorological stations in the area as a symbol of its sovereignty.

Upon learning of the Argentine action, and fearing that it was merely the first move in Argentina’s efforts to gain control of the long-disputed Falkland Islands, Churchill’s war cabinet authorised the top secret Operation Tabarin.

“The expedition was intended to bolster a sovereignty that had been weakened by decades of apathy and indecision by successive British administrations,” explained Stephen Haddelsey, author of Operation Tabarin: Britain’s Secret Wartime Expedition to Antarctica 1944 – 46.

“[Britain] needed to maintain its claims to the territories… any failure to defend its rights could have profound implications for other parts of the Empire.”

LIFELONG FASCINATION WITH ANTARCTICA

The man chosen to lead the expedition was James Marr, a 41-year-old Royal Navy reservist from the village of Cushnie in Aberdeenshire and one of the country’s leading authorities on the Antarctic continent.

“By any standards, Marr’s career had been extraordinary – and the vast majority of it had been spent in the field,” revealed Haddelsey.

“Marr had spent almost his entire adult life at sea, often working in the most extreme conditions on the cold, wet, windswept decks of polar research vessels.”

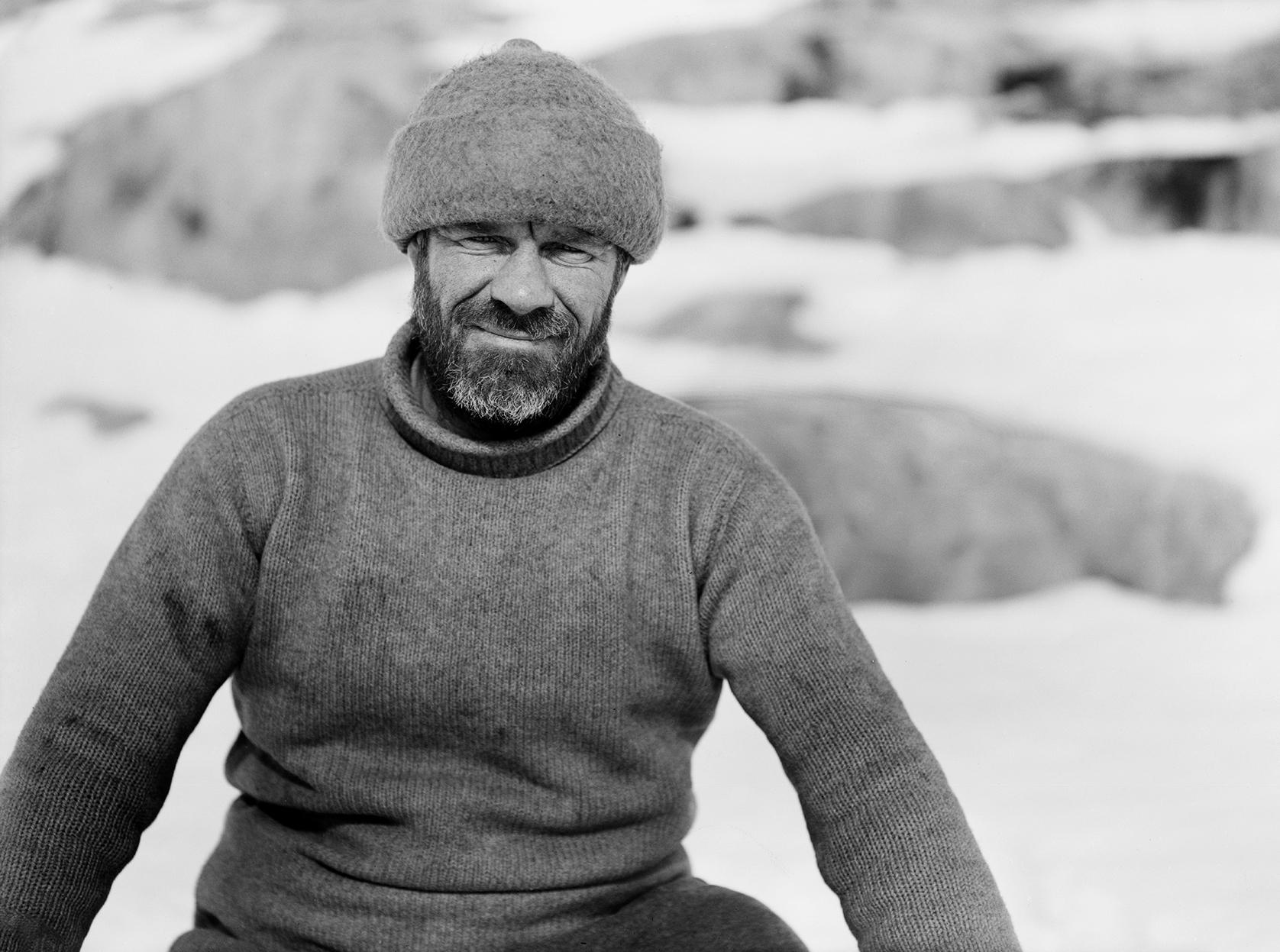

Born in 1902, he was described by one fellow explorer as possessing “a dour Scots face – like a prize-fighter”. But Marr’s hard-bitten exterior concealed a warm, friendly nature.

“He retained a pawky sense of humour, enjoyed inventing jingles, playing his harmonica at bar-room sing-songs and performing comic turns to round off an evening’s entertainment,” said Haddelsey.

Marr’s lifelong fascination with Antarctica was kindled as a teenager when, as part of his studies on marine life at the University of Aberdeen, he won a place on an expedition to the Antarctic led by Ernest Shackleton aboard the research ship Quest.

But the expedition was cut short when Shackleton died of a heart attack on January 5, 1922 at South Georgia.

However, the legendary explorer’s death did nothing to diminish the young Marr’s enthusiasm for polar exploration. After earning a BSc in marine zoology, he would return to the region on four more scientific expeditions over the next 17 years.

GRUELLING CONDITIONS

The outbreak of World War II looked to have ended Marr’s Antarctic research, at least for the duration of hostilities, but to his surprise in August 1943 he was recalled to London by the Admiralty from the Indian Ocean – where he was serving as a lieutenant on a mine-laying ship – and invited to lead a highly secret mission to his beloved Antarctica.

“He accepted on the spot,” revealed Haddelsey.

“As one contemporary wryly remarked, ‘A return to the south was an altogether more congenial prospect than mine-laying in the tropics.’”

Promoted to lieutenant-commander, the next three months were a hectic whirl of activity as he set about organising the expedition and recruiting the other team members, an eccentric collection of polar experts, scientists and Royal Navy officers, many of whom were fellow Scots.

On December 14, 1943 the men set sail from Avonmouth aboard the troopship Highland Monarch, travelling across the U-boat-infested Atlantic Ocean and arriving in the Falkland Islands six weeks later, where they transferred to the elderly exploration vessels Fitzroy and William Scoresby.

For the next two years the team sailed between Britain’s remote, icebound island colonies in the Antarctic, planting a Union Flag on each and building small bases to reinforce British sovereignty.

On several occasions the explorers found signs of Argentine occupation on British Antarctic territory.

But the feared confrontation with the Argentine military never came to pass, Marr’s group encountering the Argentines just once, on Laurie Island in February 1945 – though neither party took any aggressive action against the other.

“The men on the ground were willing to treat their opposite numbers with courtesy and even affability, leaving their respective governments to rattle diplomatic sabres,” explained Haddelsey.

“Operation Tabarin’s first and only meeting with the forces of Argentina ended in a cordial stalemate.”

The greater enemy proved to be the gruelling conditions, the men encountering fierce blizzards, avalanches and temperatures that could drop as low as -40 Celsius. Coupled with the heavy workload, Marr’s health began to suffer.

ALL BUT FORGOTTEN

Twelve months into the expedition, the team’s medic Eric Back reported that Marr was “suffering from mental and physical exhaustion”.

His condition steadily worsened during the first weeks of 1945, Back recording that: “He is the type of man who will not give in but keeps on and on until he is exhausted.”

It soon became clear to all, not least Marr himself, that he would be unable to continue.

After appointing Canadian Andrew Taylor as his replacement, he was evacuated back to the UK in February 1945.

Marr’s departure was a major blow to Operation Tabarin.

“I had a very great regard for Marr,” one of his colleagues on the expedition, Welshman Gwion Davies, said years later.

“It’s only looking back on it I realise what a fantastic job he did; it would have driven me round the bend. I could never have done it.”

But there was still much work to be done, and for the next 12 months, while world-changing events were unfolding in Europe and the Pacific as World War II reached its climax, the men of Operation Tabarin quietly got on with the job of exploring the Antarctic continent.

Finally, after more than two years in the Antarctic the expedition returned to a war-weary and economically exhausted Britain, only to discover that in their absence they had been all but forgotten.

“No arrangements of any kind had been made for their reception and three of the party were reduced to spending their first night in England sleeping rough in a disused air raid shelter,” revealed Haddelsey.

Marr’s successor as expedition leader, Andrew Taylor, was especially bitter about their treatment: “When we left England in 1943, the entire operation [was] shrouded in secrecy… the quietness of our departure was only exceeded by that of our return.”

But while the expedition ultimately failed to resolve Britain and Argentina’s territorial disputes in the region, the scientific discoveries made by Marr and his team were found to be of great importance.

“Even the briefest glance at the huge mass of scientific and geographical work completed by the expedition can leave no observer in any doubt that Operation Tabarin left an indelible and overwhelmingly beneficial mark on the Antarctic continent,” commented Haddelsey.

After making a full recovery, Marr went on to work for the National Institute of Oceanography in Surrey until his death at the age of 63 in 1965. He never returned to the Antarctic.

Operation Tabarin: Britain’s Secret Wartime Expedition to Antarctica 1944-46 by Stephen Haddelsey, published by The History Press is now available to buy in hardback.