Situated in an idyllic rural landscape overlooking the sparkling waters of the Caledonian Canal, the Victorian residents of Inverness would have been impressed by the grand bay-windowed sandstone building being built.

But for decades the sight of the building – Craig Dunain Hospital – brought hope and a sense of fear in equal measures as it was built as a “lunatic asylum”.

On May 19, 1864, Inverness mariner Donald Donaldson became Craig Dunain’s first patient.

According to the hospital’s ‘Register of Lunatics’, his bodily condition was “insecure”, his disease was “paralysis” and his form of mental disorder was “dementia”.

He died just a few months later of what were described as “pecuniary losses”.

NHS Highland consultant in public health and medicine, Dr Cameron Stark, says he would have liked to have looked into Donald Donaldson’s eyes.

Having reviewed Donald’s case notes he said: “I’d have liked a look at his pupils – syphilis might not have been a major surprise.”

The case notes on the first patient, which are stored in the NHS Highland Archive within the Highland Archive Centre in Inverness, are typical of those of many of Craig Dunain’s earliest inmates in that they reflect only a limited understanding of mental illnesses.

Donald’s notes read: “Some years ago it is stated he was treated for delirium tremens and that pecuniary difficulties from the loss of his vessel brought on the present attack of insanity which is stated as having been characterised by violence, destruction of furniture and very dirty habits.”

The notes state that Donald suffered from general paralysis which particularly affected the limbs. It was also difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain what he was speaking about.

After his admission, Donald suffered frequently from “hemiplegic attacks of the right side.

“He was extremely restless, rolled his head from side to side, shouted at the top of his voice for days and assumed an aspect of perfect terror when approached.

“The paralysis increased to such an extent to render the patient perfectly helpless and to deprive him of the power of articulating.”

Speculating on Donald’s condition, Dr Stark suggested that, as he was a mariner, he may well have had syphilis.

He said: “There are two main possibilities: an unremitting chronic mental illness or a progressive neurological disorder. It sounds most like tabes dorsalis and GPI (general paralysis of the insane).

“It would be interesting to know if his wife ever had symptoms.”

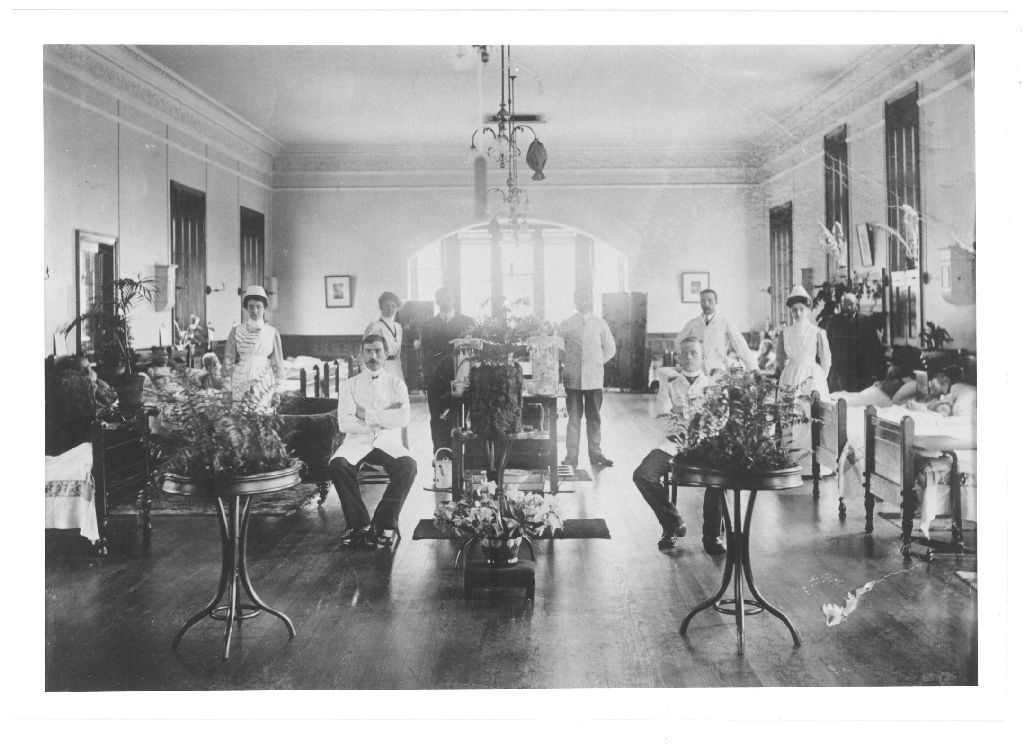

Craig Dunain – which became known locally as ‘The Craig’ – was opened as the Northern Counties District Lunatic Asylum, with accommodation for 250-300 patients, and was the third district asylum to be opened in Scotland.

Just 15 years later, The Craig had 360 inmates, and was described as “greatly overcrowded.”

The Craig was extended over the years and by the start of the World War II housed 852 patients; in 1964 there were almost 1,100.

“Craig Dunain represented the very dawn of asylum life in Scotland,” said Dr Stark, “and for many people at the time it was a place of genuine hope.

“The treatment of the mentally ill before asylums was truly terrible. If you were poor, you were very much better off in an asylum.

“Asylums offered a degree of care – you were fed, you were warm and you were given something to do, such as work on the farm or in the laundry.

“And while Victorians had a limited misunderstanding of mental illness, I’d be fairly modest about our current understanding.

“We still don’t know what causes any of the major mental illnesses, although we know a lot more about biology and risk factors.”

Among the most striking aspects of Craig Dunain’s earliest records are the reasons given for patients being admitted.

Disappointment in marriage; excitement from anticipated marriage; losing a Highland Games competition; intemperance; greed; attendance on religious meetings and sleeping exposed to the sun are all cited as suspected causes of insanity.

But according to Thom Shaw, lead pharmacist at New Craigs Hospital, which replaced Craig Dunain after it closed in 1999, equally striking was the treatment patients received.

Beer, wine, brandy, opium and creosote all feature as having been prescribed to some of the early patients by The Craig’s doctors.

Mr Shaw said: “They were very paternalistic and were doing their very best for patients, putting them in an environment where they were fed, clothed and sheltered.

“However, in relation to the medication – and maybe that word should be in quotation marks – absolutely nothing they used would have treated the underlying mental disorders as we would perceive them today.

“In modern psychiatry, everything hinges on diagnosis, and it’s quite clear that in Craig Dunain’s earliest days they didn’t know what they were dealing with.”