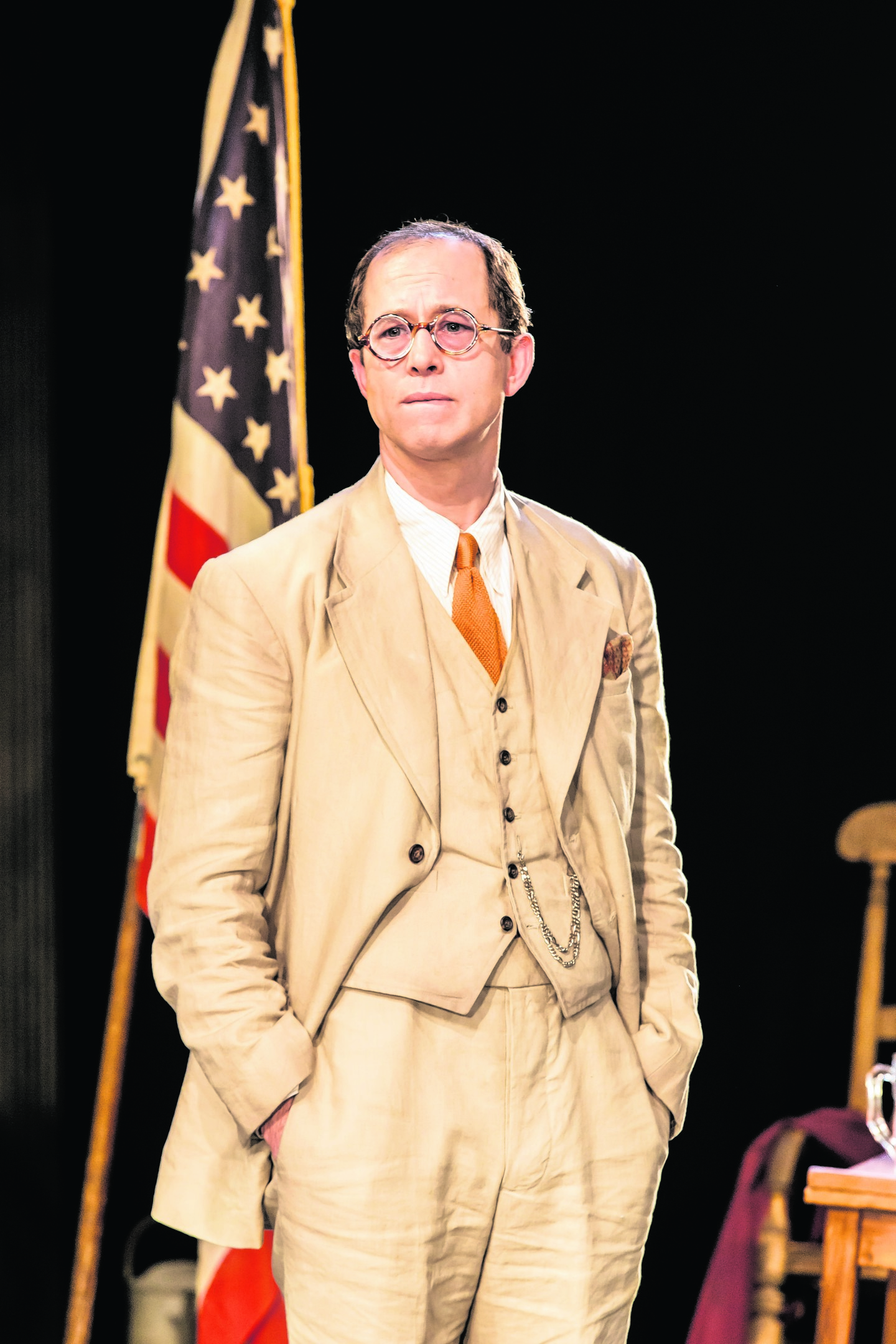

Bringing three dimensions to the archetypal good-guy role has been a complicated mission for actor Daniel Betts, but a rewarding one nonetheless, writes Andrew Youngson

There’s a particularly arresting scene in Christopher Sergel’s stage adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird. The spiky themes of racial prejudice, class dispute and rape converge in a courtroom summation delivered by Atticus Finch – the lawyer who carries the moral weight of the 1930s-based American play.

In making his impassioned speech about the innocence of Tom Robbins, the kindly black man accused of rape by a young white woman, Atticus turns to the real audience. They are now the jury.

“He approaches them and you can feel the whole atmosphere change,” said David Betts, who plays Atticus in the current UK tour.

“For the audience, it really becomes no longer about ‘we’re watching a play. I know I’m in HM Theatre in Aberdeen, and I’ve just parked my car’. It’s about thinking ‘for two hours, maybe I can persuade myself that I’m in Alabama and I can feel the heat and the sweat, and I can believe in the light and dust’. That speech breaks down the convention of being in a theatre. We’re asking the audience to feel they are responsible for the fate of Tom Robbins.”

It’s a powerful way to express the themes of To Kill a Mockingbird – themes which still hold unsettling currency in the modern world. When it was first penned in novel form by Harper Lee, the story of Atticus, his young children, Scout and Jem, and their battle against the racial tensions of the deep south, Mockingbird was an incendiary piece of prose.

While winning a Pulitzer for Lee, and becoming staple reading for students and adults alike, it touched many a raw nerve. And it still does today, as is exemplified in the take-home messages which the producers of the Regent’s Park Theatre production have chosen to fly high.

“If the audience leaves with a sense of nostalgia, thinking ‘isn’t it awful how black people were treated in the 1930s’, then we have failed,” Daniel said.

“Because the sad truth is, 70 years on, we’re in a worse state. If the book tries to teach us anything, it’s about tolerance, understanding, and trying to see through the eyes of another human being, while mirroring back on their own lives – so that you can try to understand ‘the other’, whether that be the colour of someone’s skin, their education or religion.”

In a world in which religious intolerance has never been more fraught, Daniel finds the story has never carried more significance. And with news this week that Lee is set to publish a sequel to her award-winning novel, featuring an older Atticus and Scout tackling racial tensions in the 1950s, it seems the past is still fertile ground for learning about the problems we face today.

“It’s incredibly shaming on us as a species that we have done so little in the years this book has been around. That’s why it still has such a powerful message.”

It’s heavy material to perform eight times a week, but thankfully there are flashes of positivity in Lee’s tale. In a partially autobiographical twist, Lee chose her narrator of the story to be eight-year-old tomboy Scout. Through Scout’s adventures with her older brother, Jem, and awkward best friend, Dill – each played on stage by a rotating cast of nine youngsters – the tale invokes the joy of childhood, while also shining a light on the special perspective young people have on adult themes.

“It’s that wonderful and extraordinary innocence. Children don’t have a side to them; they say it as it is, and cut through the adult cleverness and rhetoric to get straight to the heart of the matter,” Daniel explained.

When it came to approaching the role of Atticus Finch, however, this child’s-eye viewpoint complicated matters somewhat. In the novel, all characters are depicted through the kaleidoscope of Scout’s senses. But on stage, all roles need to be three-dimensional characters in their own right. And so, for Daniel, adding extra shades to the archetypal figure of “Atticus the Good” required some digging.

“Playing a decent or good man can be a bit limp. So I tried to look to other things, and the biggest thing was this idea of grief and loss. His wife died only four years before the story,” he explained.

“So that’s of course a huge part of his story. It’s in those areas that we see his functionality of trying to do right by his kids while carrying the weight of his loss. That’s what I found interesting to bring out in the character. Whether or not I’ve achieved it is for other people to decide. But that’s been really enjoyable for me to play.”

Early on in the story, Atticus is appointed to the case by the local judge – an impossible case, given the odds stacked against Tom Robbins. Despite the impenetrability of racial prejudice he has to tackle, Atticus makes the case his life’s mission. This moral fortitude in the face of adversity explains why, in the years since Lee’s novel was published in 1960, and portrayed on film in an Oscar-winning performance by Gregory Peck, Finch has become canonised as the ultimate figure of good in ethical and legal matters.

But Daniel doesn’t place him on a pedestal. To flesh out the role properly, he explained, it has been vital to avoid revering Finch.

“He’s just an ordinary bloke who has a strong moral compass. So, yes, he’s a Christ-like figure, but in another way he’s an antihero. He’s a man who has been cast in the role of an avenging angel, and as this civil-rights activist, but he’s really not. He’s an ordinary bloke,” he said.

It’s in Atticus Finch’s ordinariness as the “everyman” that his strength of morality lies. He’s simply a man who knows right from wrong.

“At the beginning of this story, as we tell it, he’s speaking to his daughter and she asks: ‘If you know we’re going to lose the case, what’s the point?’ To which he replies: ‘Simply because we were licked 100 years before we started, is no reason for us not to try to win.’”

To Kill a Mockingbird runs at HM Theatre, Aberdeen, from Monday, February 16, to Saturday, February 21. Show times are 7.30pm daily, and matinees on Thursday at 2pm and Saturday at 2.30pm. Tickets are available from www.aberdeen performingarts.com or by calling 01224 641122.