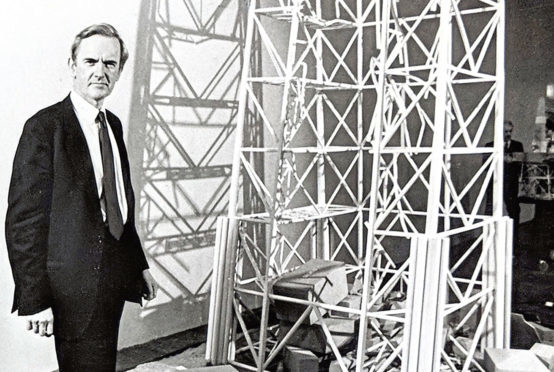

Piecing together precisely what happened, why it happened and how to prevent another Piper Alpha happening again took Lord Cullen two years and 400 pages. The impact can be seen across the industry today and his verdict on the present state of offshore safety continues to hold great weight.

If anyone knows whether the lessons of Piper Alpha have been learned, it must be Lord Cullen.

He spent the best part of two years poring over the details of the night and taking evidence from huge numbers of people.

The result was a weighty 400-page, two-volume report containing a staggering level of detail, including a lengthy section on what sort of noise the first explosion made.

No stone was left unturned.

The workings of Lord Cullen’s keen, analytical mind can be seen on the pages as he wades through the haystack of information, with some pieces of evidence supported, while others are picked through and cast into doubt.

Catastrophic failures mounted to cause the initial explosion, and other shortcomings contributed to the situation deteriorating as quickly and fatally as it did.

The rig exploded in the first instance after gas leaked and ignited.

Lord Cullen concluded that the gas came from a pump which should not have been activated because a metal disc was being used as a stop-gap while a pressure safety valve was being checked.

Warnings missed

He found that shortcomings in the handover between shifts and in the execution of the permit to work system meant operators were unaware that the valve, which would have prevented the leak, was not in place.

At a higher level, warning signs in the months and years leading up to the disaster were missed and not acted upon. At the end of his report, Lord Cullen made 106 recommendations for improving safety on oil rigs and floating installations, all of which were implemented.

Thirty years on, the suitability of the current North Sea safety regime continues to be scrutinised.

Could it happen again?

Naturally, there is some doubt, but recent reports haven’t shied away from making dire warnings.

Industry technical advisers DNV GL recently published a report showing nearly half of oil and gas professionals believe not enough has been invested in safety in recent years.

Worryingly, less than a third were committed to remedying the situation.

DNV GL vice-president Graham Bennett said that while processes and procedures had improved, he “would not rule out the possibility” of another catastrophe on the same scale.

A week before, the Health and Safety Executive said some operators had come “perilously close to disaster” in recent years and that more had to be done to reduce gas release incidents.

Safety 30 conference

Addressing the Safety 30 conference, held in Aberdeen to mark the Piper Alpha anniversary, Lord Cullen said the events of 1988 remained “highly relevant” and that underlying reasons for major accidents tend to recur.

He has been struck by how frequently disasters have been previously met with “warning signs” either through reports, a previous incident, or signs of danger in the workplace.

Piper Alpha was no exception.

Speaking at the conference, he said management had “failed to accept” signs of danger in the years of the world’s worst offshore disaster, despite “being in no doubt” of what the consequences of an explosion would be.

These included a series of reports outlining the dangers to structural integrity of the platform, and how such a fire would be “almost impossible to fight”.

Lord Cullen concluded that management had shown a “dangerously superficial approach” to safety.

“Management had not accepted that this would happen. They had rejected the installation of subsea isolation valves and fireproofing of structural members as being impractical.

“They had relied on emergency shutdown valves and limited deluge system, both of which were wrecked by the initial explosion.

“They had not carried out a systematic identification and assessment of potential hazards or put in place adequate measures for controlling them but had merely relied on a qualitative opinion.

“It showed, in my view, a dangerously superficial approach,” he said.

Several other major accidents since Piper Alpha

His address used examples from several other major accidents that had taken place since Piper Alpha, including the Texas City oil refinery explosion and Buncefield oil refinery fire in 2005, and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Each one, according to Lord Cullen, had safety warnings which were either “misread as innocuous”, “treated as commonplace”, or “did not give rise to concern”.

Fifteen workers were killed and more than 180 others were injured in the Texas City refinery explosion in March, 2005.

The explosion was caused by an ignition of an oil vapour cloud due to an overflow from a piece of processing equipment.

Lord Cullen said this incident had been preceded by other fires on the site which were not properly investigated and had been treated as “nothing to worry about”.

The fire at Buncefield in England in December 2005 similarly was the result of an overflow of petrol due to the sticking of a high level switch, with vapour again igniting, causing a fire which raged for two days.

No one was killed but 40 people were injured.

Lord Cullen said this case was a result of a lack of adequate response to the gauge sticking, despite “clear signs” it wasn’t fit for purpose.

He added that there had been pressures to keep the site operating without safety getting the attention it needed.

Finally, he used the case of Deepwater Horizon at the Macondo oil and gas well where an assumption about a safety process was treated as fact, having fatal consequences.

Eleven workers were killed in the Gulf of Mexico explosion in 2010, with a resultant spill of millions of barrels of oil, largely considered to be the worst environmental disaster in US history.

Following an operation to plug the well with cement, drillers “dismissed” indicators that an integrity test had failed, and had therefore “normalised signs of danger” that the most important defence to a blowout had failed.

Lord Cullen said these cases, among others like the 2003 Columbia space shuttle disaster, showed the value of the experience of others, and that management should lead the way in safety culture.

He said: “In some cases there was an investigation but it was limited in scope or was superficial, or its results were not driven home to forestall further trouble. In other cases there was no investigation, the signs did not give rise to concern, or even curiosity. Some signs were treated as commonplace or misread as innocuous so there was no corrective or preventive action.

“They seem to indicate at least three factors. First, poor safety awareness. A prerequisite of which is competence for that purpose. Secondly, a failure to give priority to safety and thirdly a failure to show or instil in others the responsibility for identifying and resolving safety issues.

“Lest you may think that in any of these cases they were simply no more than human error, I must say that the accidents, practices and values of the workforce are often shaped by the tone set by management. That’s another chapter in the book of lessons.”

Cullen recommendations lifted safety standards and improved conditions

Lord Cullen’s inquiry into the Piper Alpha disaster set forth 106 recommendations aimed at lifting safety standards in the North Sea.

Perhaps the most important of those said the UK’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE) should take responsibility for safety in the UK continental shelf, instead of the UK energy department.

The department had been responsible for overseeing production and safety, which was seen by some as a conflict of interest.

All of Lord Cullen’s proposals were accepted by industry and responsibility for their implementation was shared with the regulator.

HSE developed and implemented another of Lord Cullen’s key recommendations.

He stipulated that from 1992 safety cases should be submitted by all operators of North Sea installations.

By November 1993, drafts for every installation had been submitted to the HSE and by November 1995 all had been accepted.

They are comprehensive pieces of work which provide full details of the arrangements for managing health and safety and controlling major accident hazards.

Safety case regulations were revised in 2005, in light of 13 years of experience, to reduce the burden of three yearly resubmissions without diminishing their effectiveness.

Even before the Cullen Report’s publication, steps were being made to enhance safety procedures.

Regulations were introduced in 1989 to give workers a voice.

They could elect, by secret ballot every two years, someone to represent them in dealings with the installation management on health and safety and to establish safety committees on each platform.