If you visit the Falls of Feugh in the coming weeks, you may well come across an enthusiastic crowd peering into the water.

Leaning over the bridge, people excitedly point as a sliver of silver bursts forth against the current.

The popular site by Banchory offers one of the best viewing spots in Scotland, with the ultimate vantage point for leaping salmon.

The fish make their way up the falls during spawning season – from February to March and September to November.

The spectacle is one of nature’s greatest shows, as it seems an almost impossible challenge for the fish to tackle.

But tackle it they do in an attempt to migrate to the Atlantic and even the Pacific Ocean.

The incredible leap is but the first of many obstacles which the fish are now faced with.

However, at some point on that journey, wild salmon numbers are being decimated.

For every 100 that leave our rivers for the sea, fewer than five return – a decline of nearly 70% in just 25 years.

Experts believe that if this alarming trend continues, the species could become endangered in our lifetime.

But what can be done to save what Mark Bilsby describes as “an iconic part of Scottish wildlife”?

Mark, chief executive officer for the Atlantic Salmon Trust, has warned we have just 20 years to halt and hopefully reverse the decline.

He joined the trust two years ago but has worked in salmon management for 25 years – in both the Outer Hebrides and Aberdeenshire.

Indeed, Mark has even chosen to make his home just outside Banchory to be close to the River Dee.

He is at the helm of the Moray Firth Tracking Project, the largest acoustic tracking project for salmon in Europe.

The ambitious scheme was launched in spring 2019 to uncover the secrets of missing salmon and help prevent further decline.

The Moray Firth is the route taken by 20% of all salmon that leave the UK.

Seven rivers are involved in the project: Deveron, Findhorn, Spey, Ness, Conon, Shin and Oykel.

One year on and the initial findings are in.

Here, those who love and work on the river, from biologists to ghillies, explain why we must act now, before it is too late.

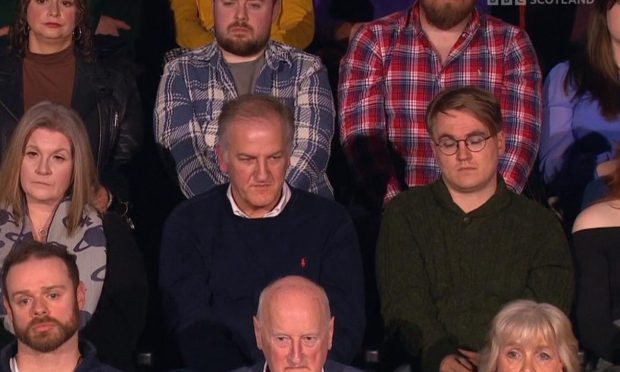

Mark Bilsby: Atlantic Salmon Trust

I’ve been sticking my head underwater in ponds and rivers since I was a child.

I’ve always been fascinated by this underwater world and I’ve been lucky enough to pursue a career in it.

Salmon are an iconic part of Scottish wildlife, both from a conservation point and culturally.

Even in Pictish times, you’ll find carvings of salmon in Angus. They have been with us a long time and salmon are incredibly rare in what they tell us about their habitat. They live in rivers for the first few years before heading out to sea.

Fish from Aberdeenshire can go as far as the west coast of Greenland.

The decline isn’t just a Scottish problem or even a UK one, it’s across the whole of the Atlantic – Canada in the west, Norway in the north, Russia in the east and Spain in the south.

We’ve gone from having eight to 10 million salmon in the Atlantic to two/three million.

I attended a parliamentary reception just last week to highlight that salmon are in crisis.

We have 20 years to do something about it. If this rate of decline continues, we may no longer have them.

Salmon is the aquatic canary of our rivers and seas.

The song they are singing is that something is terribly wrong, they are not thriving.

Why? Well that’s a pretty big question which has been met with lots of opinions.

You can’t change policy with an opinion – the world and his wife has an opinion.

We looked around to see if people had worked on similar problems.

There was a professor who looked at cod stocks in the Irish sea as cod went through a major decline.

Like any good schoolboy, we copied his homework. It translated to salmon.

We followed the young fish from seven rivers out to sea for the first 100 kilometres to find out where they are dying and what they are dying from.

This involved fitting 800 fish with an acoustic tag, no bigger than a paracetamol tablet.

The fish are unharmed by the tag.

We put 350 receivers in the rivers and out at sea.

They formed a big curtain – the biggest one went from Spey Bay to Brora.

We’ve been massively supported by Glasgow and Durham Universities.

Then there has been support from the seven river trusts, with people giving up their time seven days a week.

There have been thousands and thousands of hours given up by volunteers.

The local fishermen were phenomenal in helping us put receivers in the right location.

People are recognising the crisis and rolling up their sleeves, whether that’s helping financially or by spreading the word, turning up on the ground to provide support – someone will have heard we need a tractor and offer one.

What we’ve found so far is that half the fish go missing in fresh water.

That suggests the problem might be closer to home.

We can’t jump to any conclusions as to why they went missing, that’s what we are focusing on next.

Is it river conditions, water quality, obstacles to fish migration?

It could be any one of a number of things.

To make sure salmon have a thriving future, we need to find out what’s causing the problem and if it’s a manageable impact.

So if it’s water quality, we’d look at land management.

We’re looking to extend the programme to the west of Scotland.

There are so many people who depend on salmon, a whole community, in fact, who make a living from fish. It is cultural and economical.

I have hope though, I really do. People have risen to the challenge.

Doctor Lorraine Hawkins believes in Mark’s vision and was instrumental in helping the team put together the Moray Firth Tracking Project.

Lorraine, director of the River Dee Trust, has been tracking salmon on the river since 2016.

Doctor Lorraine Hawkins: The River Dee Trust

The River Dee is a special area of conservation.

If we lose salmon, then we stand to lose our freshwater pearl mussels and otters as well. It’s a knock-on effect.

We started tracking juvenile salmon smolts in the river four years ago – it’s an easier environment than the sea.

We discovered we were losing 25% of salmon before they even made it out to sea.

We started looking at factors such as predation and river flow.

The main predator is a bird called a goosander, which has ferocious teeth.

So we’ve been scaring the birds away.

Salmon provides a welcome boost to the rural economy, it brings in millions of pounds each year in Deeside. Salmon is part of the culture here.

Will we return to the numbers we had 30 years ago? Maybe not.

But I do think if we act now, we can save the species. We have time to get to grips with what is happening to salmon.

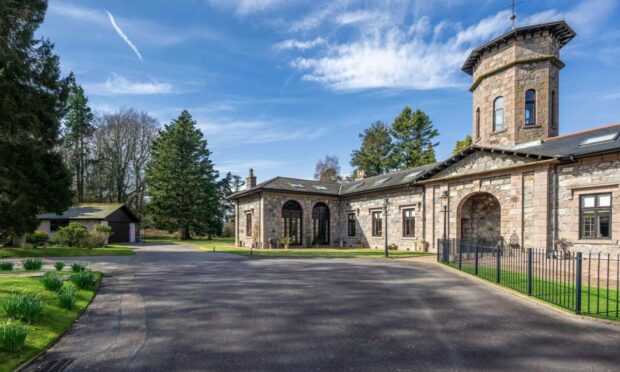

Ian Tennant and David Buley make a living from life on the water as ghillies on Gordon Castle estate.

They are preparing to welcome in the fishing season on the River Spey and believe they are “ambassadors” for the river.

If salmon continue to disappear, so too could their livelihoods.

Ian Tennant: Head ghillie, Gordon Castle Estate

I’ve been a ghillie for 40 years. When I first started out, the salmon numbers were tremendous.

It is in the last 20 years that salmon numbers have declined rapidly and that means less anglers are coming.

It could have a major impact on the valley. Hotels rely on anglers, as do guest houses.

Then you’ve got the local shops, even the butchers.

It is a big spin-off.

There was a slight improvement last year, but numbers are still way below what they were.

In the olden days, you’d easily get 2,500 fish. Now we’re looking at around 700.

David Buley: Ghillie, Gordon Castle Estate

I’ve been a ghillie since I was 21 years old. I’ve been involved with some round-table talks recently, so many organisations have come together to help with revival. We need the government to care, that is the key phrase.

Fishing has been labelled as an industry for rich English toffs. It’s not like that at all.

There’s eight of us who work the river, we are working class.

This is a fragile rural community and fishing tourists are vital.

They come here to spend money; jobs are on the line.

I’m still optimistic, though, this is just the beginning of people coming together.

For more information on the Moray Firth Tracking Project, visit atlanticsalmontrust.org