In the middle of the 20th Century, all around the UK, a lot of herring gulls made a choice that would prove massively consequential for their descendants and city residents alike.

Or maybe it wasn’t actually their choice. But more on that later.

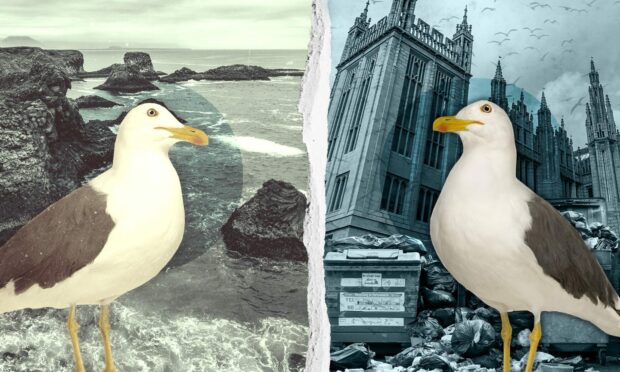

In their tens of thousands, the birds flocked from the coastal regions and islands where their species had lived for millennia, and found a new home among the shops, offices and housing estates of urban Britain.

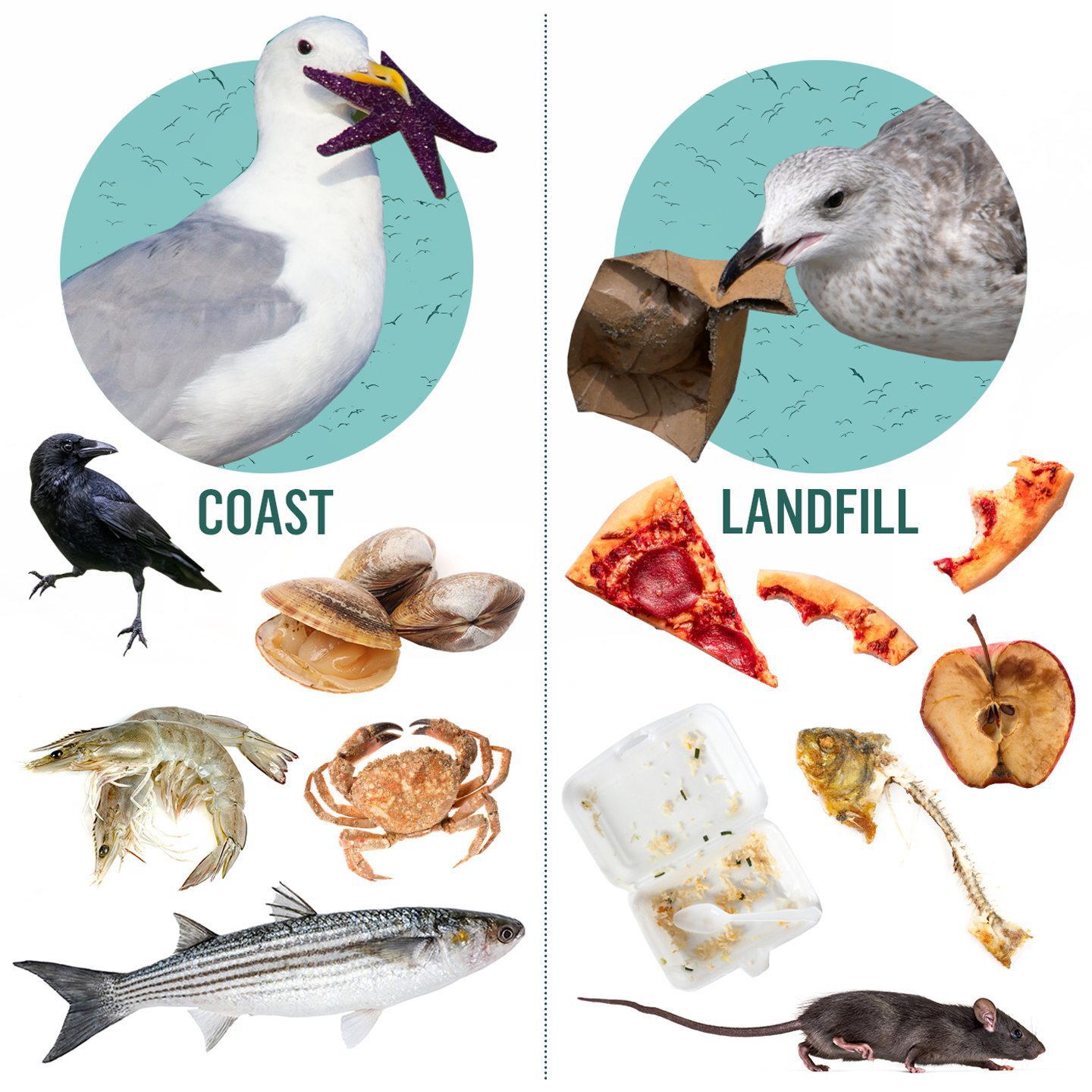

This was the Age of the Landfill: across the country, in volumes never seen before, household waste was being tossed in vast piles to decompose – or not – at a smell-proof distance from the nearest settlement. Out of sight, out of mind.

But what the landfillers didn’t know was the opportunity they were presenting for a bird that was used to fighting for scraps.

It did not take long for gulls from the coast to discover this unimaginable bounty, and realise they could eat much more reliably from the diverse offerings of the rubbish heap than from their more traditional options on the seashore.

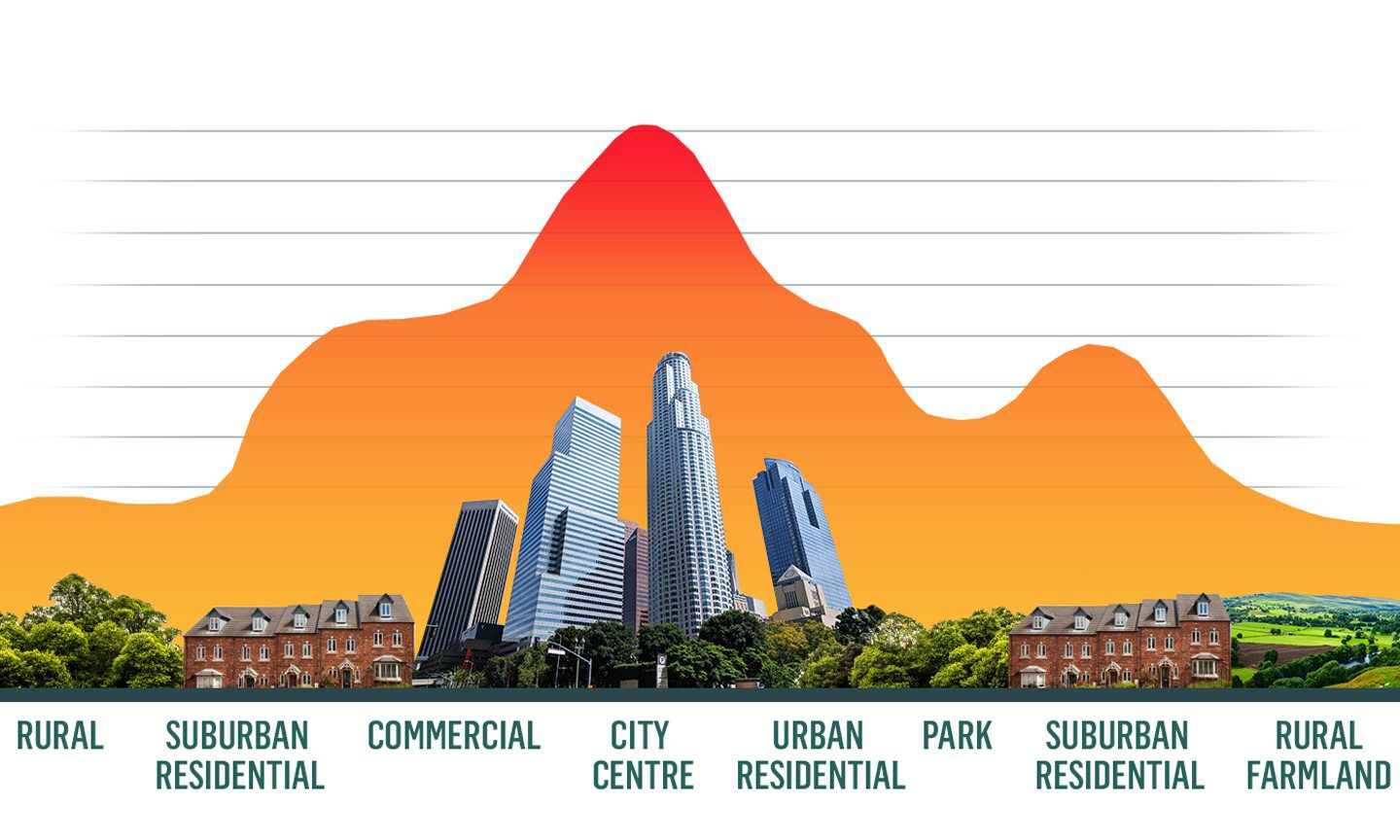

And what’s more, the human activity around the nearby buildings meant the temperature in that area was a little higher (called an “urban heat island” by the experts) and that, combined with a lack of predators, made it an ideal place to nest.

We are still within a normal human lifespan of the great urban gull boom, but these days the birds are as familiar a sight in cities like Aberdeen as pigeons or sparrows.

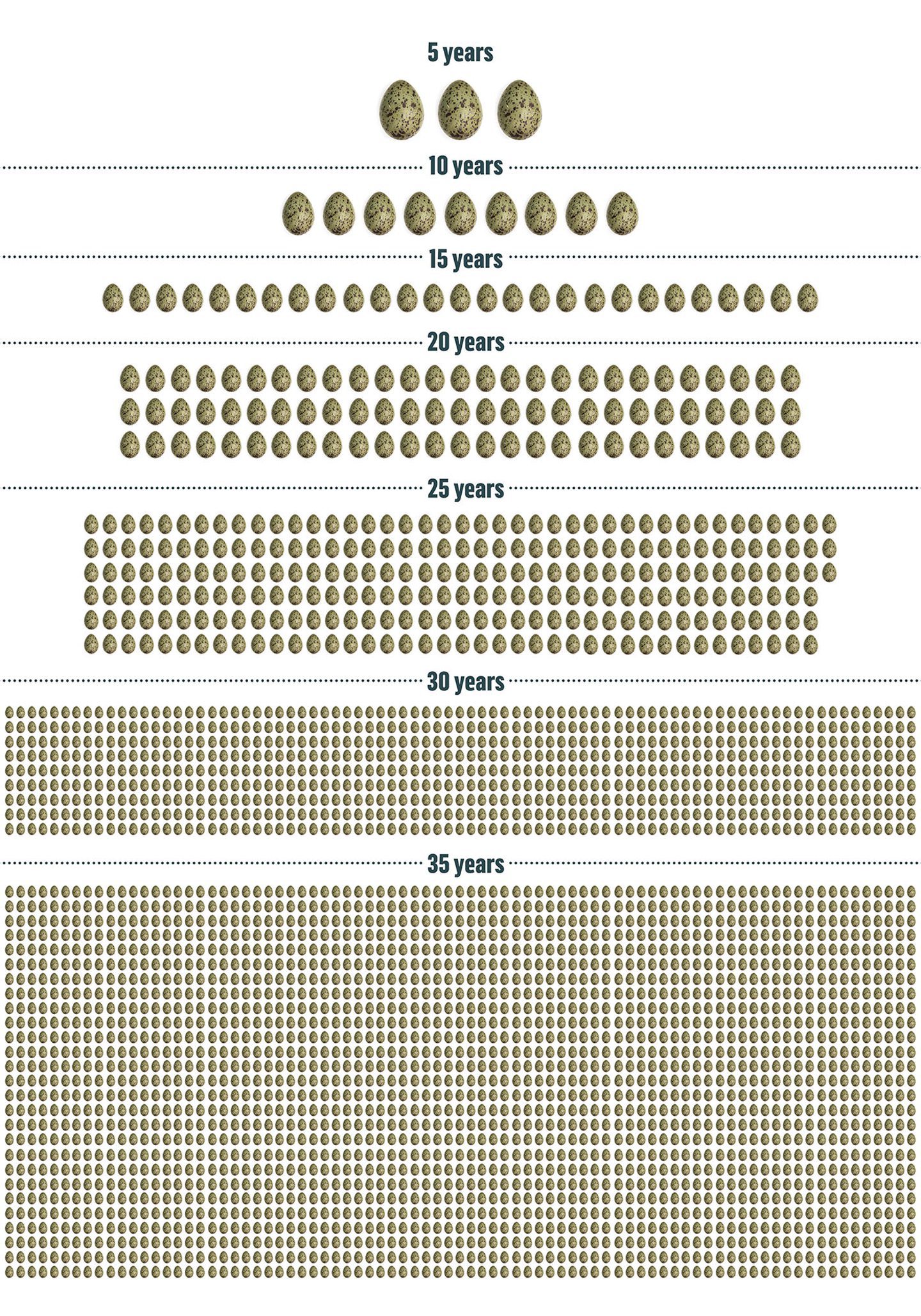

“They lay three eggs a year on average, so they can raise up to three chicks a year, and then the chicks tend to come back and breed in the same location they were hatched,” said Viola Ross-Smith of the British Trust for Ornithology, who holds a PhD in gulls.

Generations of urban seagulls

“If they’re raising up to three chicks a year in the city, then they’re all coming back four or five years later to nest on rooftops and have their own chicks, you can see how the urban colony can really quickly take off.”

As seagulls breed at around five years old, that means 14 or more generations of them may have lived their entire lives in a particular town, village or city since the mid-century move, with the population increasing each time.

They’ve also spread out, with reports of herring gulls nesting as far inland as Braemar and Birmingham.

So why do we keep hearing this mantra of gull numbers going into shocking decline, and the species being placed on the Birds of Conservation Concern Red List?

Dr Ross-Smith said: “They’re on the Red List because of their decline at the colonies that are monitored by the seabird monitoring programme.

“There are various sites around Scotland where seabirds are monitored, and these are all more remote locations – it’s there that they’re doing really badly.”

Does this mean that the people who say they can’t believe the birds are on the list because there are so many in the city have a point? Could it be true that the status doesn’t actually cover the full picture?

“I would be surprised if the numbers in cities are completely offsetting the decline elsewhere,” Dr Ross-Smith said.

“So overall I’d be surprised if we don’t have fewer herring gulls than we had 20 years ago or 40 years ago.”

City move may have saved seagulls

The official statistics say that the population is down around 50% from its peak in the 1980s, a jaw-dropping loss. A fuller picture will emerge next year when the results of the JNCC’s latest seabird census are released.

But surprisingly, Dr Ross-Smith says the mid-century seagull pioneers who made the momentous move from coast to city may have actually prevented an even more dramatic decline.

She said while urbanisation has been “disastrous for their reputation”, it has been positive in most other senses.

“It hasn’t been disastrous for their numbers, because if they weren’t in the cities, I don’t know how many of them would be in the wider countryside because in some of these coastal colonies they’ve had year after year of breeding failure.

“They’re long-lived birds, so it takes a few years of breeding failure for that to translate into the birds disappearing altogether as the adults die off.”

Not much of a choice?

As for the reasons for those failures – well, that is why the seagulls’ initial choice to move away from their traditional habitats may not have been much of a choice at all.

Humans not only created the ideal conditions for seagulls to want to move into the city – a wide variety of food, warm places to nest – they also created the conditions that made it necessary to leave the coastline.

And for the same reasons, Dr Ross-Smith believes it may be impossible to reverse the urbanisation trend.

She said: “In an ideal world, there would be a really suitable habitat for gulls on some nice islands where humans can go and look at them and say they’re lovely seabirds, then they can go home and not worry about their car being pooed on.

“But that relies on there being undisturbed parts of coast that aren’t going to be developed, that haven’t got dog walkers or water sports, or port activity.

“It relies on there being plenty of fish in the sea that birds could rely on instead of relying on our own human refuse to eat.

“Everything’s just a bit out of balance now, they just can’t do that anymore in the wider marine environment.”

Instead, we may just have to take responsibility for our insatiable desire for urban expansion and learn to live in harmony with our new neighbours – at least, as far as that is possible.

“I feel like in some ways, gulls hold up a mirror to ourselves,” said Dr Ross-Smith, “and what we see isn’t necessarily what we want to see.”

Conversation