An old chicken shed near Inverurie might seem an unlikely venue for a party, but that didn’t deter revellers from pitching up for a rave in 1992.

The acid house music subculture from the late 1980s and early 90s has come back into fashion through new films and retrospective exhibitions.

As nostalgia grows over the halcyon days of the rave movement, we look back at the arrival of the underground music scene in rural Aberdeenshire.

Hundreds descended on old chicken shed

By 1992, the Conservative Party had been in government for 13 years and their policies were becoming increasing unpopular with the disaffected youth.

Even more so when a police taskforce was set up to tackle acid house parties and shut down venues.

But this succeeded only in pushing the movement underground.

Instead, covert free parties were held in abandoned warehouses and industrial sites. And in Aberdeenshire? Chicken sheds.

Hundreds of people travelled from far and wide to descend upon a dilapidated chicken shed at Keithhall for an all-night dance extravaganza in April 1992.

An ancient, rural parish above the River Don near Inverurie, Keithhall is dominated by the sights and sounds of agriculture.

Except on that Saturday night.

As darkness fell, booming rave beats disturbed the usual calm – and frightened a group of young Brownies camping nearby.

Grampian Police received a flurry of calls.

Music echoed across the countryside

Although the rave scene was alive and kicking across the UK, local residents weren’t quite ready to embrace it on their own doorsteps.

The 10pm-8am all-nighter at Keithhall was called Core III and organised by a man who went by the pseudonym “Bagsy”.

Initially, the rave was to be held at a farm near Montrose, but plans changed at the eleventh hour.

The justification for running the contentious event was that it was a charity fundraiser.

Instead, around 400 dance fans – “including coachloads from Aberdeen and Dundee” – headed north and descended on the run-down chicken shed at West Hillhead Farm, Keithhall.

Residents were raging when “non-stop music echoed across the countryside” through the night until 10am, and found their roads blocked by “convoys of cars”.

Meanwhile, organisers of the Brownie camp said it was “a very alarming experience” for the unsuspecting girls of 1st Hatton unit, who probably thought the most excitement they’d have that night was a midnight feast.

Brownie guider Elizabeth Forrester added: “It was pitch dark and people were wandering about outside.”

Shed raves should be ‘stamped out’

The old shed, more accustomed to animals of the feathered variety than party animals, was described by attending police as “large and dilapidated”.

An unlikely venue for dancing and debauchery, nevertheless, Grampian Police described scenes of “unacceptable chaos” and debris at the roofless shed.

And officers sought to warn hallkeepers and farmers across the region of the ramifications of turning a blind eye to such events – which had the potential to attract drugs.

Outraged Gordon District Provost James Lawrence declared: “This sort of thing has to be stamped out.

“Something must and will be done.

“It is a matter of public safety and order.

“It’s just as well no-one at Keithhall needed the emergency services.

“The road there is extremely narrow and access would have been impossible.”

‘People are ignorant of what goes on’

The incident was angrily labelled as the latest in an alarming series of “acid house parties” held in the north-east.

But indignant organisers told critics they were “ignorant”.

Defending the rave, which was raising funds for Linn Moor Residential School in Aberdeen, organiser Bagsy said: “I am fed up of people thinking such events are evil.

“People of all classes go to these things because they know they are going to have a good time and get value for money.”

The 32-year-old blamed media hype for the perception that all raves were drugged-up dances.

He added: “If I was a parent I would be concerned about my child’s welfare at these so-called raves, but it is only because people are ignorant of what goes on.”

Far from being evil, the organisers waived entrance fees, instead asking for a donation towards the school which helped young people with moderate to severe support needs.

In fact, the charitable cause was so highly regarded that a number of items including signed football shirts were donated for a raffle.

And the music acts – DJs Mark Finnie from Aberdeen and Michael Kilkie from Glasgow, and bands Breze and Biology – played at low rates to support the fundraising.

‘Shady’ characters not allowed at raves

Bagsy explained the chicken shed was only secured hours before the event when the Montrose venue fell through, and what’s more, he had informed police first.

Only one noise complaint was received from a nearby resident, and Bagsy added: “We turned the music down and there were no further complaints.

“The road was certainly not blocked as cars were parked on the owner’s land.”

He said: “We are 100% against drugs and have security men at the entrance to stop anyone who looks shady.”

Bagsy said the only reason they held a rave in a chicken shed was because police and local authorities wouldn’t give him a chance to host in conventional venues.

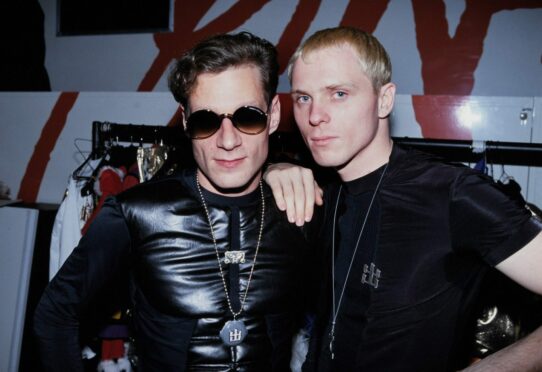

Although police discovered few raves in Aberdeenshire, Aberdeen was put on the map later in 1992 when electronic dance act The Shamen – who hailed from the city – topped the charts with controversial song Ebeneezer Goode.

Conversation