Has it really been 20 years since we welcomed in the new millennium?

Perhaps you’re still recovering from the global celebrations that saw the US Navy submarine Topeka position itself 400 metres underwater – straddling both the international date line and the equator.

Nelson Mandela lit a candle in his former cell at Robben Island at the stroke of midnight, while the Eiffel Tower was illuminated by 20,000 strobe lights.

The then prime minister Tony Blair said the “confidence and optimism” should be bottled up and kept forever after he celebrated with the Queen at the Millennium Dome.

In Edinburgh, five tonnes of fireworks were set off in four minutes in the city’s largest Hogmanay celebrations to date.

Around 15% of rubbish swept up in the centre of London consisted of Champagne bottles after an estimated 3 million revellers took to the streets the night before.

Thousands of people still turned out for a millennium day parade on January 1, and bells were rung simultaneously in churches and cathedrals around the country at noon.

The Granite City was the first in the UK to light its millennium beacon, with a free street party in Union Street.

But as the bells chimed, there was a more sobering situation that threatened to bring the entire country, if not the world, to a halt.

As people hugged each other and linked hands for Auld Lang Syne, dedicated teams could do nothing but wait – for potentially the worst to materialise.

Hospitals, airports, banks, even the oil industry in the north-east, were preparing to be hit by the Y2K bug.

In the months leading up to the millennium, experts warned that many computers would not cope when the date flicked over to 01/01/00.

It might sound inconsequential, but millions of pounds was spent on making sure that software would not malfunction.

Also known as the Millennium Bug, it was feared that computers would recognise 00 as 1900.

As a result, activities that were programmed on a daily or yearly basis would be damaged or flawed.

Power plants depended on routine computer maintenance for safety checks, such as water pressure or radiation levels.

Not having the correct date would throw off these calculations, and possibly put nearby residents at risk.

And computers with records of all scheduled flights were also threatened, because few, if any, airline flights were in existence in 1900.

These examples are but the tip of the iceberg for what could have been a global crisis.

It is still hotly debated as to whether Y2K was a money-making myth or a genuine threat, with tech workers divided.

Countries such as Italy, Russia and South Korea, did little to prepare for Y2K.

They had no more tech problems in comparison with the US, which spent millions to combat the problem.

We spoke to the experts tasked with averting disaster in the north-east, and discovered what went on in the months leading up to the year 2000.

NHS Grampian spent thousands of pounds on cataloguing, assessing and evaluating equipment and systems.

A year 2000 coordinator was appointed, and a special control room was set up for New Year’s Eve.

A news letter issued to staff stated: “The millennium will bring many challenges, some of them possibly within minutes of its arrival.

“But the view is that the Aberdeen Royal Hospitals NHS trust will be well prepared and able to deal effectively with anything that arises.”

The trust was assessed and achieved blue status, making it “year 2000 compliant”.

Plans and preparations made in the face of Y2K were judged satisfactory, according to the government’s independent assessment programme.

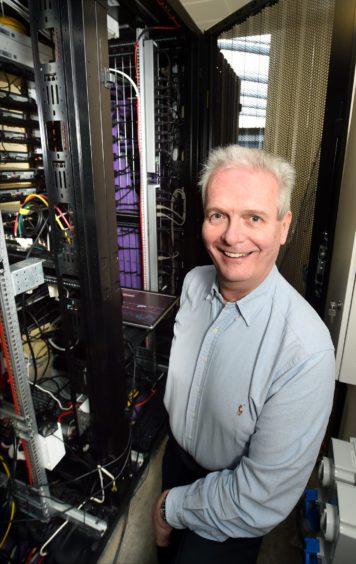

Derek Adie, who is telecoms manager and senior technical analyst at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (ARI), can recall the preparations in the lead-up to December 31.

“We must have started preparations in July – there were a lot of stories on Y2K in the papers,” he said.

“I was looking after the switchboard on New Year’s Eve, you had to assume that the service provider had also done preparations.

“I think we all knew that everything was going to be fine, but that was because we had done the ground work.

“There were 15,000 extensions across the whole of Grampian, alongside 44 GP practices and four major sites.

“So it was a pretty big deal, but we were confident that nothing was going to happen.

“I think the manager who was appointed for the evening was stood down at 4am.”

For Bill Smith, Y2K had the potential to bring an entire network down.

Although he is currently communications manager at NHS Grampian, rewind 20 years and Bill was a systems engineer for BT.

“The implications of Y2K were huge, because at the time BT was used by pretty much everyone,” he said.

“It was the network for 999 calls. My aim was to ensure that the network survived.

“It was all to do with clocks embedded in the processes in computers.

“We didn’t know if computers would start to look backwards when the clock reached 00.

“Anything with a computer chip on it had to be checked.

“I think the biggest fear was that something would happen.

“We were ready to make all these manual changes if needed.

“I was advising BT customers on what we were doing to secure their systems.

“It was a way of giving customers some confidence, that we had everything under control.

“Practically everything had a computer chip in it, from the microwave to your wee watch.

“Everything as we knew it was going to stop. That really was the fear.

“It didn’t dampen the celebrations, though.

“It was the best celebration Union Street had ever seen

“When nothing happened, it was a told-you-so moment in the sense that there was a bit of bravado to it.

“We all breathed a collective sigh of relief.”

Y2K also had the potential to shut down oil platforms.

For Ian Phillips, chief executive of the Oil and Gas Innovation Centre, the Millennium Bug posed a very real threat.

“I was a director for Halliburton at the time,” said Ian.

“We took sensible precautions. Oil platforms shutting down was a possibility, and that would obviously have a commercial impact through loss of production.

“We obviously had software systems running on equipment offshore.

“So we decided not to have them in operation on New Year’s Eve, so as to avoid anything going wrong.

“I think the fear was the unknown consequences.

“When midnight came, would the computer act as if it was a whole century earlier?

“What would it do?

“It sounds simplistic, but it was a significant concern.

“An awful lot of money was spent by businesses all over the world.

“I think there are two schools of thought.

“Either job well done, or what was all the fuss about?

“There wasn’t a fuss, because we did the necessary preparations in the first place.”

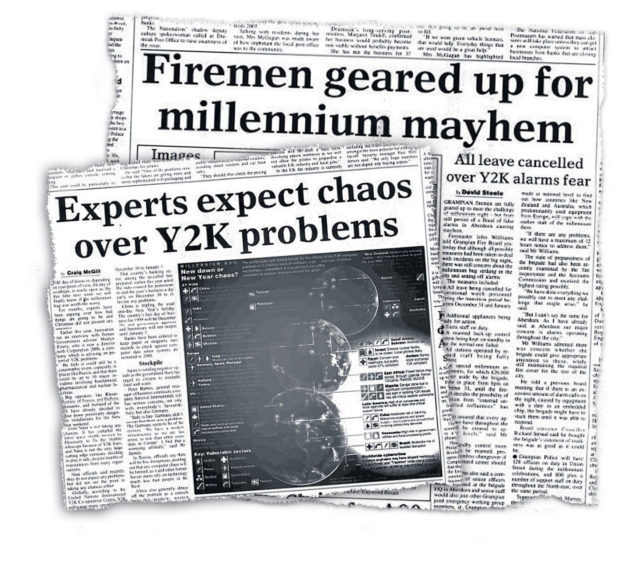

Jeremy Cresswell can recall a deep sense of panic across the north-east, which he believes was partly caused by hype in the media.

Then head of business at The Press and Journal, he now questions the “myths” surrounding Y2K.

“There was blind panic coming from some directions, complete with dire predictions as to what was going to happen,” said Jeremy.

“Y2K was very much a thing, it had been talked about for years.

“Then nothing happened, nothing major anyway.

“As to how many glitches there were on a smaller scale? Well, those never made the headlines.

“Y2K was sold well enough for people to take it seriously.

“The oil and gas industry had bigger problems to think about, though.

“Y2K did not cripple the North Sea.

“In 1999, oil was just beginning to come out of the second oil-price crisis.

“There was a huge effort by the industry to fix itself.

“So companies were more invested in driving through strategy on recovery.

“They were battling to get revenues rebuilt.

“The millennium actually heralded the most positive bull run ever experienced by the oil and gas industry in the North Sea.

“So Y2K seemed irrelevant, although systems were obviously checked.

“Bigger things were going on, though.

“The world did not come crashing down around our ears.

“If you were a little business, it was your own crisis – relatively easy to fix.

“If you were a global corporation, it was a different matter.

“A little bit of me says that Y2K was a myth. It was a plausible myth, though, because it made people check their systems regardless of whether they believed it or not.

“Even if you were the local council, you still acted on a precautionary basis.

“I think we can still see elements of Y2K today.

“It’s 20 years on, and an incredible amount has happened.

“But in my mind, the concept of Y2K begins and ends with people trying to turn their computer on in the morning and thinking, will it work?

“For most of us, it was nothing more than that.”