Ever since Rachel Helliwell was a kid, she remembers her dad being out on the River Spey with a fishing rod in hand.

He always fished on one particular estate, and after 45 years had got to know the stretch of water pretty well.

But the last few seasons have been among the worst in living memory. The Atlantic salmon that once crowded these waters have nearly disappeared.

“He is very sceptical of climate change,” Rachel said. “So when I said it was probably this which was affecting his fishing, he didn’t believe me.”

Record-breaking water temperatures

Rachel is more equipped than most people to make this assessment. As a senior research scientist at the James Hutton Institute in Aberdeen, she has dedicated her career to all kinds of water research.

“I decided to find out what was happening in the water of the Spey which might be affecting salmon,” she said.

“I thought it would be really difficult but actually my dad said that ghillies take various river measurements morning and night each day – I had no idea this was the case.”

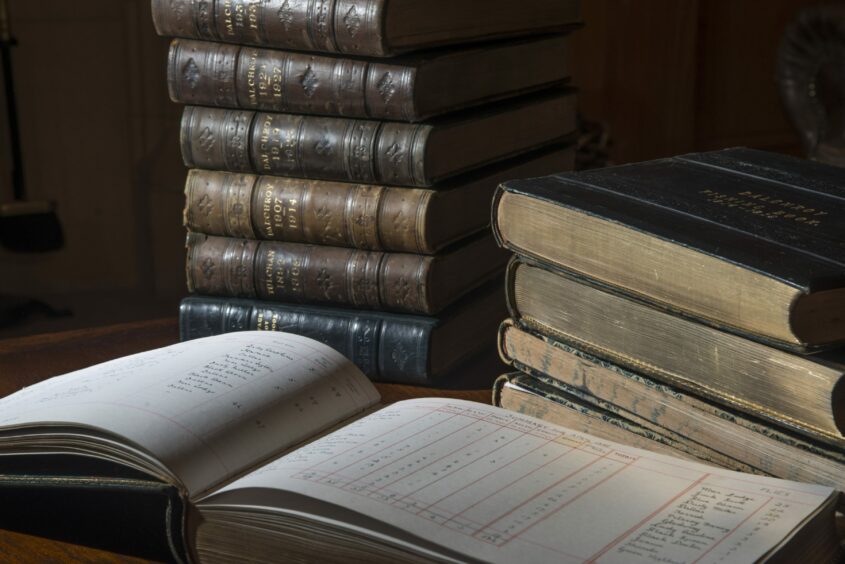

For the next few months, Rachel and her colleague Dr Ina Pohle poured over stacks of leather-bound books which recorded everything from water levels to fish size.

They found that certain tributaries of both the Spey and the Dee were reaching record-breaking temperatures of 27.5 degrees Celsius and that over the last 100 years the average water temperature had increased by more than two degrees.

“That two degrees is really significant,” Rachel said.

“Salmon can cope with slightly warming waters, but when it gets consistently warm like that the oxygen levels in the water drop and fish have problems feeding and breeding. Plus disease seems to become more common.”

Why is the water heating up now?

There are a few inter-linked reasons why the waters are heating up.

Changing weather patterns have led to less snow accumulation in the mountains. What is there melts faster too thanks to the milder weather.

That means the snow melt isn’t there to cool down rivers when they need it most.

The topography of the land also means the both the Spey and Dee are wide and flat in places, with no trees to offer shade.

Under the glare of the sun, the riverbed heats up and retains that heat for many hours, warming the water as it flows downstream.

All this might have answered a few questions for Rachel’s dad, but for Rachel herself and the rest of the team it posed a new question; what to do about it?

The surprising benefits trees offer wild salmon

At the River Dee, action has already begun.

A plan is in place to plant one million trees by 2030. More than 250,000 are already in the ground and another 70,000 are waiting in the wings for this season.

Many thousands of these trees are being planted directly along the river bank with the intention of shading the water from the sun.

“It’s all about protecting the river for the future,” said Lorraine Hawkins, director of the Dee District Salmon Fishery Board ·

“The added bonus is that these trees will absorb carbon and improve biodiversity throughout the whole catchment.”

For Lorraine and others working on the Dee, the situation is getting desperate.

Back in the 1960s, anglers on the river would be landing more than 10,000 fish a year.

Now they are lucky to hit 3,000.

“Those numbers don’t even include the netting catch too,” Lorraine said, “that stopped in the 1990s in an effort to protect stocks even then.”

She explains that the catch and release policy was introduced soon after for the same reason.

The trouble is, the salmon are being affected “at both ends” as Lorraine puts it.

They are struggling with the warm, shallow waters of the river as well as disease and changing temperatures of the sea.

“We know for an absolute fact that numbers of returning salmon are declining,” she said, referencing the lower numbers of fish which return to the Dee to spawn.

“In the 1970s we used to get about a 40% return rate, now we are lucky to get 2%.”

Improving the habitat of the Dee by introducing more tree cover is one attempt to make sure the salmon are as healthy and strong as possible before going out to sea – in the hope they are able to one day come back.

Could ‘green’ hydroelectricity be to blame?

But the mouth of the river isn’t the only problem, as Spey Fishery Board director Roger Knight explains that the source has its own issues.

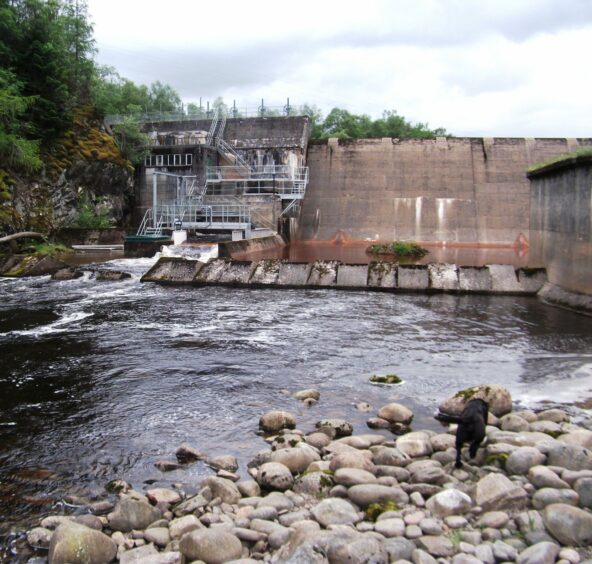

“Approximately 85% of the top reaches of the Spey are diverted to the Spey Dam,” he said.

“This water is redirected to Fort William to generate electricity to make aluminium, and when it’s done that it ends up in Loch Linnhe – nowhere near where it originally came from.”

A second hydroelectricity project redirects yet more water away from the Spey.

This one diverts water from two important tributaries (the Tromie and the Truim) to generate power before ending up in the River Tay.

Less water means that the river is getting shallower and warmer, bad news for all of the species which depend on it.

“This is denuding the Spey and its tributaries of its ground water supplies which are supposed to top up the water at times when the flow is low,” Roger said.

“Not having it is having a devastating impact on the ecology of the river and the biodiversity it supports.”

Roger explains that he is not against hydropower but wants the Scottish Government to recognise that although it is renewable, hydro is not as green as it seems.

The Spey Dam was constructed in 1942 to meet the increased demand for aluminium prompted by the outbreak of WWII.

“Yes we needed it at the time, but it’s outdated technology that we are still using 80 years later,” Roger said.

“This is much bigger than just salmon.”

The Spey is a designated Special Area of Conservation for various species, particularly renowned for its freshwater pearl mussels – the population of which has declined by 50% in the last decade, says Roger.

“People will say ‘oh it’s because of climate change and not having enough rain’ and yes, that is part of the problem but extracting water for the hydro projects is just compounding the issue,” he said.

“Atlantic salmon are in crisis and something needs to change.”