Michael Alexander hears about the night in 1834 when a surgeon robbed the poet’s grave and stole his skull in the name of science

While the poetry of Robert Burns is mainly moving, melancholic and thoughtful, studies of his works suggest that the spectre of death was never far from his thoughts with references to epitaphs, reflections, and musings on the dead.

Burns wasn’t above the gritty detail either, as his “Epitaph for William Nicol” shows: Ye maggots, feed on Nicol’s brain. Having been poorly for much of his short adult life, Burns was only too well aware of his own mortality.

A Bard’s Epitaph, written in 1786 when he was just 27, suggests he never expected to see old age.

But Scotland’s Bard could hardly have imagined events after his death when his skull was stolen by phrenologists who believed that studying his cranium could crack the secrets of his success.

Born on January 25 1759, Burns died of rheumatic heart disease at his home in Dumfries on the morning of July 21 1796, aged just 37.

His funeral took place on Monday July 25 1796, the same day his fifth surviving child, Maxwell, was born.

He was interred in the far north-east corner of St Michael’s Churchyard in Dumfries; a simple “slab of freestone” – which still survives – being all his wife, Jean Armour, could afford.

In the years following his death, Burns’ admirers came to believe that his simple grave was an insufficient memorial to the poet.

A circular was published by John Syme on November 29 1813 calling for the public to subscribe to the cost of a mausoleum.

Eighteen local worthies attended a meeting in the George Inn in Dumfries on December 16 1813, and the project to fund a fitting public subscription memorial was launched.

Among those who took a leading part in the fundraising campaign was Sir Walter Scott.

One of the subscribers was the Prince Regent, later George IV, who gave 50 guineas.

Money flowed in from all over Britain and from as far afield as India and America.

More than 50 designs were received through a public competition with the plans of Thomas F Hunt, a London architect, being adopted.

From the moment of its completion, and the private exhumation of Burns’ body on September 19 1815 from his original simple grave at one end of St Michael’s churchyard, Dumfries, to his new mausoleum at the posh end of the same cemetery, Burns’ Mausoleum became a place of pilgrimage.

Yet at a time when grave-robbing was the talk and the scourge of Scotland, Burns’ own skull would be controversially removed from the new grave some 19 years later in the name of phrenology – the fledgling “science” and ultimately misguided belief that you could infer much about an individual’s character and their traits from the lumps and bumps of their skull.

Phrenology was a hot topic of debate in Scotland after 1814 when Spurzheim’s theory of phrenology was first published in English.

However, despite the pseudo-science being immediately debunked, this did little to dent the widespread belief in it as a science.

“In the first half of the 19th Century, advocates of this pseudo-science were busy doing all they could, by fair means or foul, to secure access to the skulls of all of Scotland’s interesting and important figures of history,” says archaeologist Douglas Speirs, former assistant keeper (Research) Archaeology at Aberdeen Museums (Arts and Recreation Department).

“The devotees of phrenology believed that armed with this new ‘science’ they could apply phrenological study to reveal and explain the greatness of Scotland’s national historical figures.

“Burns was an obvious, high-value target for study, but understandably, his wife, Jean Armour, would not give consent for these weasels to get their hands on her deceased husband’s skull.

“This obstacle was overcome in 1834 when Jean Armour died and was buried with her husband.”

Mr Speirs explained how local phrenologist and Dumfries Courier editor, John McDiarmid, had long lamented that the opportunity had not been seized to make an examination of Burns’ skull in 1815, when his body was exhumed and transferred to his mausoleum.

With Jean dead, there was now a chance of getting to the bard.

Contemporary newspapers report that permission was given by Jean’s brother, Robert Armour, to access the skull for research.

However, Mr Speirs says that when scrutinising newspaper coverage of the time, it’s “deeply questionable” what consent, if any, was really given.

“It’s clear that the only person at Jean’s funeral with authority to give permission to access the skull was Jean’s eldest son, Robert,” says Mr Speirs. “But they didn’t ask him.

“The fact that the report is so vague about Mr Armour, coupled with the fact that Burns’ skull was not retrieved when Jean was buried next to her husband in his mausoleum when she was interred on April 1 1834, is deeply suspicious.

“Indeed, the very vagueness of the so-called ‘permission’ that ‘Mr Armour’ gave, his lack of authority to give such permission, and the fact that the retrieval of the skull was done so secretly and in such a manifestly dodgy, grave-robbing manner makes it abundantly clear that the phrenologists had absolutely no family consent and no legal right to break into the bard’s tomb and steal his skull.

“It’s abundantly clear that what took place was essentially unconsented grave-robbing tidied up in the local newspaper with a bit of fake news.”

Mr Speirs says that as a ring-leader, the Dumfries Courier editor John McDiarmid “parked his impartiality” when reporting the events of his own actions and was “remarkably liberal for the time”, demonstrated by the lengthy commentaries in his newspaper on prison reform, suffrage and Catholic emancipation.

By the standards of the day, he was a “reform-minded liberal leftie”, hence his view that it was justifiable that “science” should trump the Christian belief in the right of sepulchre. This was not a popular view at the time and that’s why they had break into the tomb at night and in secret.

Mr Speirs said the group was led on the night of March 31 1834 by Archibald Blacklock, aided by the editor John McDiarmid, Adam Rankine, James Kerr, James Bogie and Andrew Crombie.

Events are described in the contemporary Dumfries Courier with the article being reprinted in innumerable newspapers up and down the country in 1834.

The night before Jean Armour’s funeral, the conspirators claim to have met her brother Robert Armour off the train and claim that they quickly extracted a reluctant “yes” from him to the question: can we borrow Burns’ skull to take a cast for phrenological study?

The gang agreed to make their way secretly and separately and meet at 7pm at Burns’ mausoleum with the intention of breaking in and taking a plaster cast of the bard’s skull.

But when they got to the graveyard, there were too many people about, so they dispersed, agreeing to meet back at the tomb at 9pm after sunset.

One of the gang kept a lookout while the rest opened the gate, entered the small mausoleum, lifted the floor slabs covering the vault below and descended into the vault using a ladder and “muffled lantern”.

The coffin casket was opened by Mr Crombie. Mr Bogie of Terraughty, who had been a member of the party who exhumed Burns in 1815 and deposited him in the mausoleum, confirmed that they had indeed located the skull he had seen in 1815.

Archibald Blacklock, the surgeon ring-leader and the team’s “man of science” and phrenologist, then made an assessment of the skull in the vault, explaining the features to his companions.

“What happened next is not reported in detail,” says Mr Speirs, “but it’s clear that the party quickly vacated the tomb with the skull in their possession, making their way to nearby Queensberry Street in Dumfries and the workshop of local plasterer, James Fraser.”

At the workshop, the gang were joined by the top brass of the town council: Chief Magistrate, Mr Hamilton, the Dean of Guild and rector of Dumfries Academy, Mr McMillan. They cleaned the skull, watched as Fraser formed a mould around it to make an imprint, then took a plaster cast from the mould.

They also all marvelled at the great size of the skull. Burns, they claimed, had a boulder-sized head. However, modern examinations of the plaster-cast skull note it to be strikingly normal.

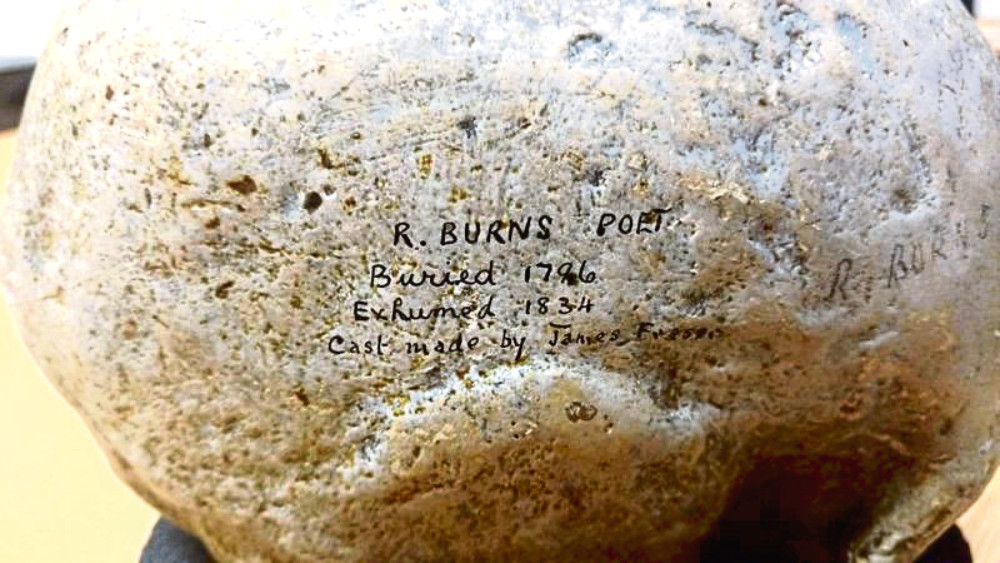

Returning the skull to its tomb, the skull-cast was sent the next day to the famous Edinburgh phrenologist George Combe.

Combe was delighted to receive the skull and within a month published in Edinburgh the “Phrenological development of Robert Burns. From a cast on his skull moulded at Dumfries, the 31st day of March, 1834”.

Combe said: “Nothing could exceed the high state of preservation in which we found the bones of the cranium, or offer a fairer opportunity of supplying what has so long been desiderated by phrenologists – a correct model of our immortal poet’s head.”

Mr Speirs says it’s not recorded how many casts of Burns’ skull were made on the night of April 1 1834. But he knows of six casts of the Burns skull that exist today.

The cast in the collection of Edinburgh University’s Anatomical Museum is the best and is almost certainly the original by Fraser.

The Hunterian Museum in Glasgow has a good-quality cast which is on loan to the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow.

The cast in the Writer’s Museum in Edinburgh lacks detail and is clearly a copy.

Similarly, the copy in Dumfries Museum lacks fine detail so must be a copy.

East Ayrshire Museums has a very poor-quality copy.

Finally, the National Trust for Scotland’s Robert Burns Birthplace Museum has a cast.

Mr Speirs concludes: “I think James Fraser made one cast late at night of March 31 1834.

“His casting process probably involved breaking the mould to get his plaster cast out, so it would make sense that he only made one copy.

“He was, after all, working in a hurry, secretly and late at night. They had to get that skull back to its mausoleum in a hurry before anyone found out that it was missing, and of course, they didn’t turn up at Fraser’s workshop until 10pm at night.”