Scottish scientists are supporting a project which is training giant sniffer rats to detect a disease devastating livestock farmers in the world’s poorest countries.

Brucellosis is a highly contagious disease that causes infertility and low milk yields in cows, sheep, goats and pigs.

Humans can be infected – causing flu-like symptoms, problems in bones, joints and the heart, and in rare cases death.

It is expensive and hard to detect, but now Glasgow University is working with researchers at Sokoine University of Agriculture in Tanzania on a project funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) to use sniffer rats to tackle the problem.

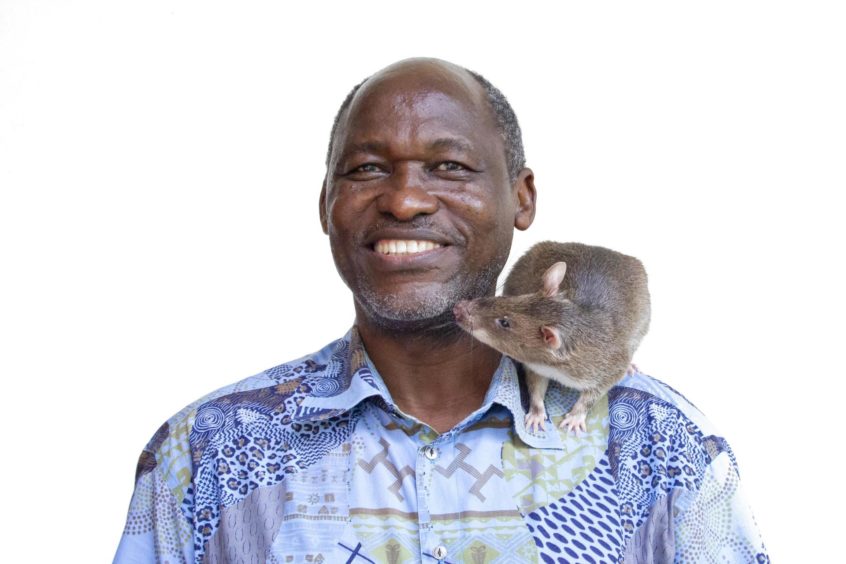

African giant pouched rats, which can grow to 3ft in length, have already been successfully trained to sniff out landmines and tuberculosis.

Now the rodent disease detectives are being specially trained to help with the blight of brucellosis.

Professor Dan Haydon, director of the Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine at Glasgow University, said the idea came about after he discovered how sniffer dogs were being used to detect brucellosis in the US.

He added: “I had been talking with someone who worked in Yellowstone National Park, where they have a brucella problem with elk, bison and cattle, and they use dogs to smell it.

“It was news to me. So, I was describing this somewhat light-heartedly to colleagues and Professor Rudovick Kazwala, who is lead researcher at Sokoine, said: ‘Aha, well, we already have this facility where rats are being specially trained to sniff landmines and tuberculosis’.

“So, we figured if they can smell landmines and smell TB, then surely we can get them to smell brucellosis? And the long and the short of it is that it turns out you can.”

Covid-19

The Covid-19 pandemic sweeping the globe highlights the importance of scientists increasing our understanding of how infectious diseases in animals can spread to humans.

Professor Haydon added: “Six out of every 10 known infectious diseases of humans are estimated to originate from animals.

“Three-quarters of new or emerging infectious diseases in humans originate from animals, of which Covid-19 represents a particularly devastating example.”

The scientists received a grant to conduct the sniffer rat research through the FCDO-supported Afrique One-Aspire initiative.

Nine rats – named Hawking, Skinner, Sloth, Stewart, Zhang, Angela, Aung, Jane, and Pipp – are now being trained to sniff out heat-inactivated brucella bacteria at the same lab in Tanzania that developed landmine and tuberculosis seeking rodents.

The giant pouched rat (cricetomys gambianus) is used, rather than the standard lab rat (rattus norvegicus), because they are easier to source in sub-Saharan Africa and live longer.

The brucellosis project is being supervised by Professor Kazwala and undertaken by masters student Raphael Mwampashi at Sokoine University in Morogoro, Tanzania.

‘Now we are using their incredible sense of smell to target brucellosis.’

Professor Kazwala, who completed a three-year PhD at the Moredun Research Institute in Edinburgh in 1996, said: “Rats have shown they were very effective in detecting landmines in projects rolled out in Angola and Mozambique, so we have moved on to disease detection.

“We had successfully trained rats to help diagnose tuberculosis and now we are using their incredible sense of smell to target brucellosis.

“The rats are conditioned over four to six months to sniff specimens. When a rat finds a positive sample, it hears a click and is rewarded. The rat learns that finding brucella means getting a food reward.

“We trained them in our new, fully automated line cage that automatically rewards the rats with tasty food pellets that they love – so they work hard to get them.”

Trained sniffer rats are already proving an invaluable tool in the fight against tuberculosis in Tanzania, Mozambique and Ethiopia where they have helped increase the detection rate of partner clinics by around 40%.

Sokoine University researchers collaborated with Belgian non-profit organisation Apopo for this programme, which has screened 621,150 samples from 411,694 patients and identified 16,221 undetected cases.

It takes nine months and costs about £5,000 to train a rat, which can then rattle through 100 samples in 20 minutes. It costs £13,000 and around two hours to analyse a single sample in a laboratory.

Basic microscope testing used in developing nations like Tanzania picks up 60% of cases at best – with that figure dropping to 20% for people also living with HIV

In Tanzania, around 28% of TB sufferers are also HIV-positive, so the sniffer rats are boosting diagnosis as they are far more accurate than basic microscopy at finding cases of TB in people living with HIV.

Widespread

Professor Haydon said: “Brucellosis is a serious problem in the world’s poorest countries. It is widespread across Africa and south-east Asia.

“It may not be a killer disease, but infected animals will fail to reproduce, calves are not born or miscarried, and milk production reduces as more animals become unproductive, costing a farmer much-needed income or their livelihood.

“This is a serious issue in nations where there is extreme poverty and the problem with a livestock disease like brucellosis is that it takes away income from the people who are vulnerable and in need.

“The World Health Organisation estimates that the global burden of human brucellosis is 264,073 years lost to disability or early death, although there is huge uncertainty around this figure, which likely substantially underestimates the true disease burden. It is often misdiagnosed as malaria.

“We have vaccines for some strains of brucella in cows, sheep and goats, but because we do not know what host species is most often causing human infection, it isn’t clear which host species is best vaccinated to reduce human infections.

“Ultimately, our hope is that sniffer rats will help diagnose infected individuals and result in faster and more effective treatment.”

It may not be a killer disease, but infected animals will fail to reproduce, calves are not born or miscarried, and milk production reduces as more animals become unproductive, costing a farmer much-needed income or their livelihood.”

Minister for Africa James Duddridge said: “The UK Government is proud to be supporting research that is not only protecting livestock – and farmers’ livelihoods – from debilitating diseases, but potentially increasing our understanding of how diseases mutate to make the leap from animals to humans.

“These Scottish Scientists at the University of Glasgow are leading the way in using innovative ideas to detect diseases faster and at a fraction of the previous cost.”