It’s a story which testifies to the strength of the human spirit and the ability of people to find a path through the darkness.

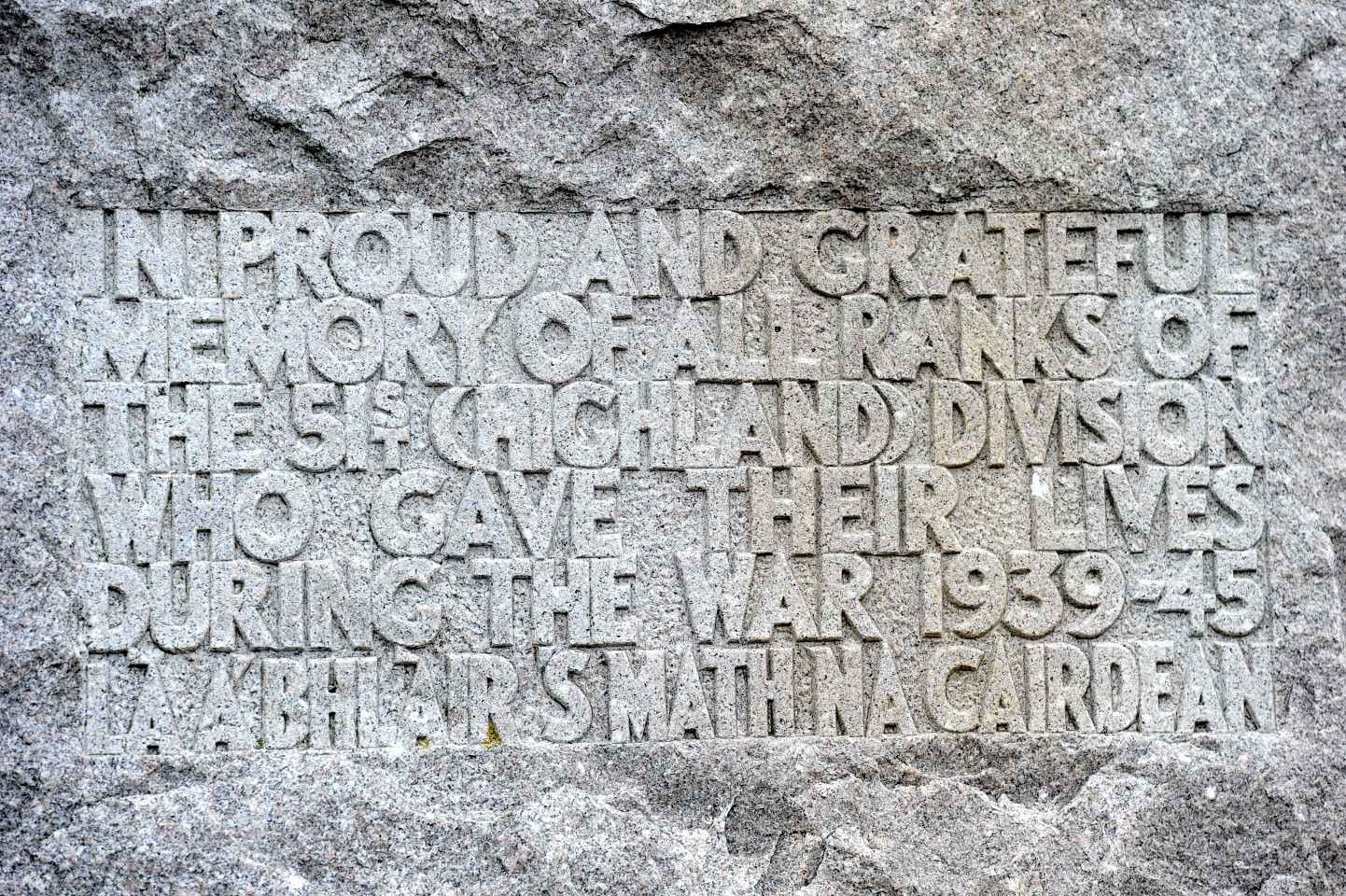

Yet, even now, 80 years after he was one of the thousands of Scottish troops who was caught up in the carnage and bloodshed at St Valery-en-Caux in June 1940, David Beaumont from Brora recalls the visceral feelings of fear and apprehension which gripped the 51st Highland Division as its troops attempted to halt a German blitzkrieg in its tracks.

Dunkirk

He had just turned 19 at the time, and had never experienced anything like the stark choice which was offered to thousands of men – kill or be killed, face insurmountable odds or surrender to the enemy – as they held up the German Army long enough to allow the mass evacuation of so many British troops at Dunkirk.

But, while the latter operation was successful, there was no reprieve for the Highlanders who were left behind, including Mr Beaumont who told his remarkable story just a few hours before he celebrated his 99th birthday.

He said: “It’s hard to describe the events of these few weeks and the huge impact which they had on so many people.

“St Valery itself was a nice little village, but it was built on a hill and there were massive cliffs on one side of it and nothing on the other and, once we had arrived there, it was pretty clear there wasn’t much chance of us escaping.

“We did the best we could and held out as long as it was possible, but there was death and destruction all around us.

“We used all the weaponry we had at our disposal, but it soon reached the stage where I only had two rounds of ammunition left and the whole area was taking a pasting, even as we tried to hold on.

”We were scared, because it was a hopeless situation. There were no (British) aircraft flying over us who might have helped, so we were on our own. And we were up against the finest in the German ranks, with (Erwin) Rommel leading the charge.

”They had an overwhelming advantage in terms of manpower, ammunition, machinery…but we stuck it out as long as we could.

“We knew there were only two outcomes – we would either be killed or we would be captured – and that is difficult to accept when you are a young man who has never experienced anything like it before.

“Eventually, of course, we were forced to surrender. But we had made a difference.

“However, that was only the start of another ordeal for those of us who were left.”

Speed of the German advance

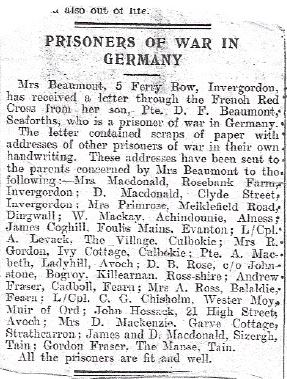

Mr Beaumont was among the many who were captured at St Valery-en-Caux while he was serving with the Seaforths.

Brigadier Charles Grant, a retired British Army officer and historian of the 51st (Highland) Division, said: “Initially, it was about 20,000 strong and comprised nine battalions of the Highland infantry regiments with supporting arms and services, including elements from England.

“They had been detached from the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and therefore managed to escape encirclement around Dunkirk.

“Instead, from June 4, they were conducting a fighting withdrawal west from the Somme under French command.

“However, the speed of the German advance was such that they, and part of the French army, were cut off, despite hopes that they would escape through Le Havre.

“Part of the division did get to Le Havre to secure it for evacuation and escaped, but the remainder were cut off and surrounded at St-Valery-en-Caux.

“Not unlike Dunkirk, a flotilla of 67 merchant ships and 140 small vessels were organised and then dispatched from several British ports.

“But the inclement weather and the German artillery who were overlooking the town meant that any evacuation on the night of June 11 was impossible.

“General Victor Fortune, who was commanding what remained of the Division considered all the options – a counter-attack, further resistance or retaking the town.

“But, against this, there was no possibility of evacuation or support for the troops.

“The men had been fighting almost continuously for 10 days against overwhelming odds. They were exhausted and virtually out of ammunition, with no artillery ammunition left at all.

“Shortly before 10am on June 12, General Fortune took the most difficult of decisions – to surrender.”

New ordeals

That judgement led to new ordeals for thousands of men including Mr Beaumont.

He was transferred to Stalag VII-B Lamsdorf and he and his fellow Scots were forced to endure a long route to the prison camp in Poland as the prelude to being inflicted with gruelling work patterns and meagre food rations from their captives.

As he recalled: “We were marched there day and night, we hardly got any sleep and we were feeling exhausted by the time we arrived.

“Then we were hosed down.

“It was all very tough for us to get through and we had to work every day in a farm or a brickworks or some other place where heavy labour was required.

“The food was…very basic. There wasn’t much of it. You know these little malt loaves which you can buy nowadays? Well, 10 of us had to make do with one of them.

“So there were a lot of very slim blokes in that camp!”

Spirit of defiance

Despite these privations, Mr Beaumont refused to become depressed or accept his situation.

His spirit of defiance never left him throughout all the months of incarceration and he was constantly seeking a means of eluding his captors.

One day, whilst out with a working party on a sugar beet farm, he and two of his fellow PoWs escaped and made their way to territory which was held by Russian forces.

In a matter of weeks, they were back with the Allies, transferred to Prague and into the hands of US forces who promptly had them repatriated to Britain.

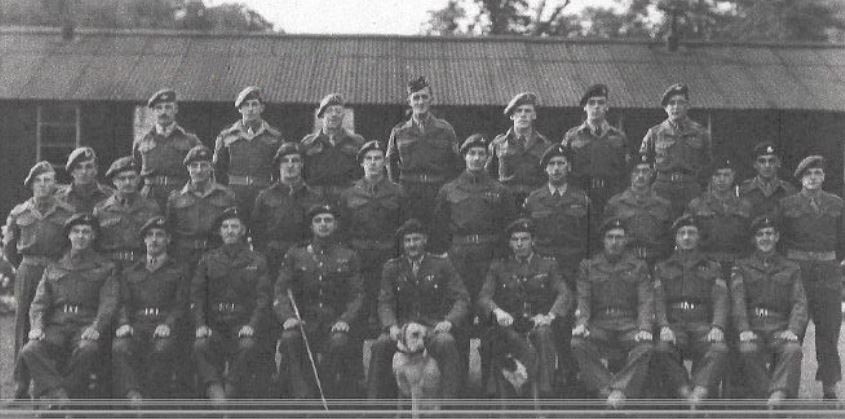

He said: “Looking back, it was a challenge to keep everything together in the camp, but we kept working and there was a lot of camaraderie between the lads. We were all in it together and I was able to get away with a couple of my mates.

“We gradually learned that the Russians weren’t too far away from where we were imprisoned, so we waited for our chance. And then, while on the farm, we took the high road and slipped away and were picked up by the Russians.

“It all passed by very quickly. One moment, we were in Poland, then we were on our way to Prague, and we were meeting up with the Yanks and finally returning home.

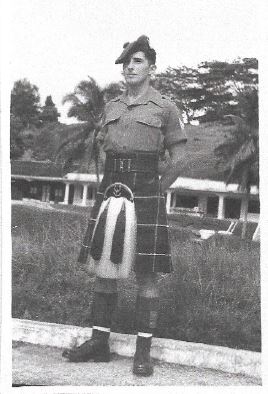

“I didn’t get back to the Highlands until the end of 1945, but I wasn’t put off by what we had gone through during the war. I relished the military life, so I re-enlisted and ended up going all over the world in the years ahead.”

Aldershot return

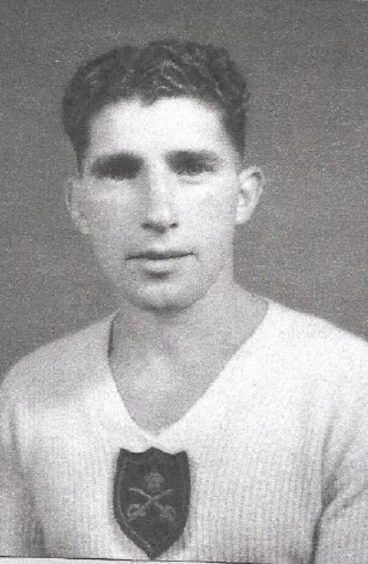

Being a keen boxer and fencer and all-round sportsman – Mr Beaumont told me proudly of how he became the army’s British welterweight champion – he was sent to Aldershot to train as a physical training instructor and was promoted to corporal.

He was then posted to Singapore, where he served with the 14/20 Kings Hussars and eventually returned to Aldershot as an instructor and was promoted to sergeant.

Mr Beaumont was born in Invergordon and now lives in Brora with his wife Ishbel, to whom he has been married for more than 60 years.

They have three children, six grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

His son, David Junior, said this week that the family were immensely proud of their father’s achievements and they were all hoping they could do something to cheer him up amid the current lockdown restrictions.

However, their dad seemed glad to be able to share his memories with other people.

He said: “There were so many lads who never came back and I’m glad they are being commemorated and that more people are learning about what happened in 1940.

”It’s important we remember the sacrifices of those who served in the 51st Highland Division because it affected so many families all across the north of Scotland.”

Given what he endured at St Valery, that is surely the least this brave man deserves.