There are some heartbreaking stories behind the victims of the 51st Highland Division’s valiant last stand at St Valery in 1940.

And the cemetery in that little French fishing village and the nearby churchyard of Manneville-es-Plains have become the final resting places for many young men who were caught up in the terrible devastation which rained down on their heads.

Played and died together

The poignant memorials at the sites testify to the sacrifices which were made and also highlight how families were torn asunder and comrades from across the north-east of Scotland played the pipes together and died together, including a group of five who were killed on the very day – June 12 – that the division surrendered to the Germans.

Stewart Mitchell, the volunteer historian at Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen, travelled to France while writing a book about the 51st Highland Division.

He said he would never forget the scenes which he encountered or the number of poignant memories which were evoked by those who fell 80 years ago.

He added: “When I was researching the Gordon Highlanders stories for ‘St Valery And Its Aftermath’, I decided to visit the area to experience for myself what the countryside and St Valery-en-Caux was like.

“In planning this trip, I had some objectives in mind, such as visiting the military cemetery in the town and the 51st Highland Division monument on top of the high chalk cliffs overlooking the harbour, where the evacuation was to have taken place.

“In addition, I wanted to visit the grave of a 5th Battalion Gordon Highlander from Ellon, whose story touched me.

“That was William Neilson and the sad thing about him was that his two older brothers, Rolland and Charles, had been killed in action in the First World War.

“William died on June 12 1940.

“Like the rest of the men of the 5th Battalion, Bill left home in September 1939 and travelled to Aldershot to complete his training before leaving for France at the end of January 1940, to join the British Expeditionary Force.

“The family had arranged a visit to the local photographer’s studio for a family photograph before he left home.

“This was duly taken with Bill, in uniform, standing proudly behind his wife, Gladys, with their baby daughter, Florence, on her knee while he rested his hand lovingly on the shoulder of their young four-year-old son, James, standing by her side.

“I knew his grave was not in the war graves cemetery in St Valery, but in the churchyard of the small village of Manneville-es-Plains, three miles east of the town.”

Mr Neilson’s burial place is situated slightly apart from a group of graves of five other soldiers, four of them Gordon Highlanders.

And, on checking the names, Mr Mitchell immediately recognised the identities of these victims, though he was not expecting them to be buried in Manneville.

They were John McLennan, 24, from Aberdeen – the son of Pipe Major GS McLennan, who was one of the regiment’s most famous figures – and Duncan Reid, 25, from Bucksburn, George Rennie, 20, from Kemnay, and Patrick (known as Peter) Stewart, 38, also from the Granite City.

Mortar shell

They died at the same time when a mortar shell came through the roof of the farm building in which they were sheltering on June 12.

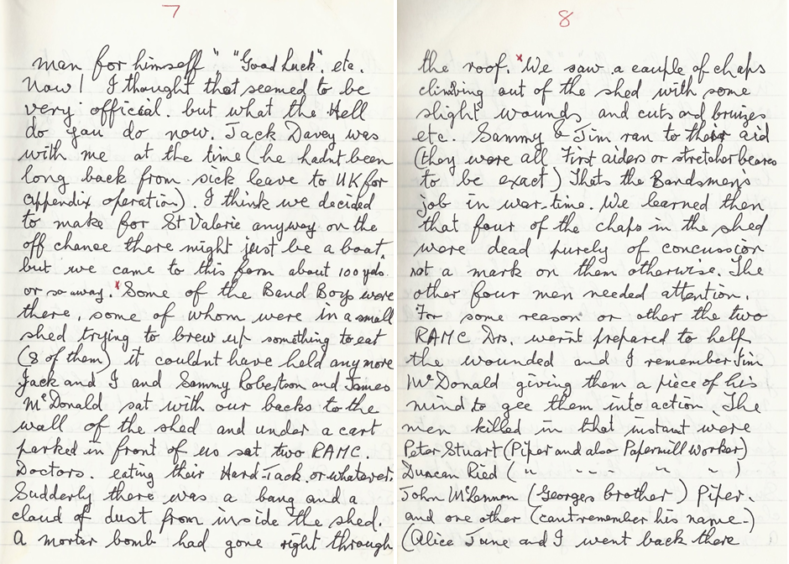

Mr Mitchell said: “I already knew the story of how they had died, because I had received the written account of the war memoir of Alex Watt, from Bucksburn, who had seen the whole incident.

“All of the Gordon Highlanders buried there had their own story. They were pre-war territorial (part-time) soldiers. Peter Stewart also left a young family and Duncan Reid’s brother, Gordon, was captured, as was John McLennan’s brother, George.

“Both spent the next five years as prisoners of war. Two other members of the pipe band, who had also been in the barn survived, but both were severely wounded.

“They were Bill Maitland, who was later on a founder member of the Bucksburn Pipe Band and James Allan from Peterhead.

“The reason I think this left such a big impression on me was that, here in this tiny village in northern France, I did not expect to find such an array of evidence of the day the 51st (Highland) Division surrendered.

Initially, he was left wondering why these men’s graves were in the churchyard instead of the war cemetery in St Valery-en-Caux.

Debt owed

But he soon found out that the reason lay in the debt which the locals in Manneville-es-Plains believed they still owed to the many courageous Scots who never had the opportunity to return home to their loved ones.

Mr Mitchell said: “I discovered later that, when the War Graves Commission came to re-inter the men in the War Graves Cemetery, the villagers immediately protested.

“They said that the men had died fighting for them and, therefore, they wished to look after their graves, and they have carried on doing so ever since.”

It is a fitting tribute to the thousands of brave lads who were left with the terrible choice – be killed or be captured – 80 years ago.