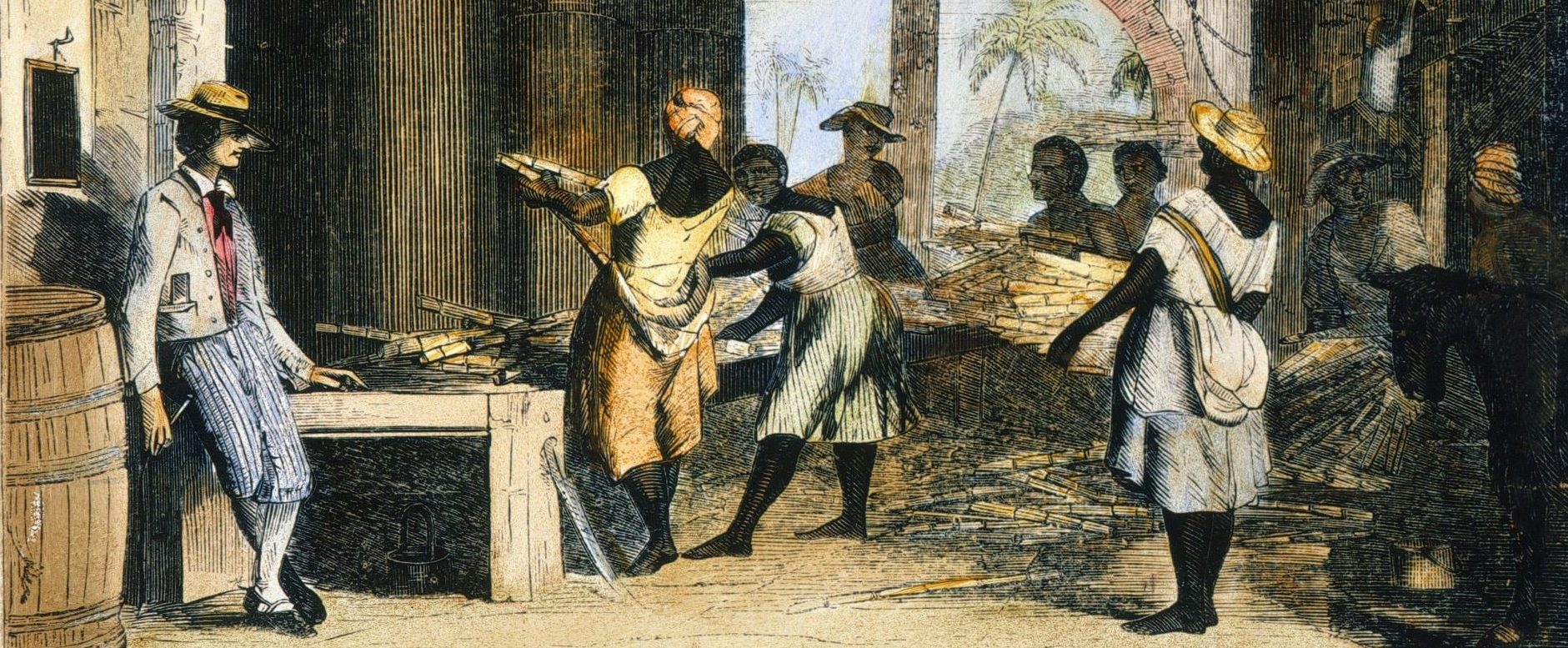

The shackled legacy of the north-east’s ties to the slave trade was left on trafficked humans sold to the highest bidder.

North-east merchants were responsible for shipping thousands of Africans to the Americas as slaves where they were given names such as Dundee and Angus.

Phone book legacy

A government slave census of 1817 recorded almost 300 slaves named Aberdeen throughout the British West Indies where they worked on the plantations, producing raw materials such as sugar, rum, tobacco and cotton, which were shipped to Britain.

Slaves were sometimes named after their owner and surnames from the north-east that appear frequently in the Jamaican phone book today include Burnett, Dyce, Forbes, Gordon, Grant, Lamont, Leslie and Shand.

Place names such as Perth, Dundee, Aberdeen, Dunkeld and Montrose still survive today as villages in Demerara, which is now part of Guyana, which hint of a hidden association with the slave trade.

When slavery was abolished in British colonies in 1833, the equivalent of £2.5bn was paid out to slave owners at about 430 addresses across Scotland.

Not a penny was paid to the people they enslaved.

“The debt the government accrued to pay that wasn’t paid off until 2015,” said Matthew Lee, a PhD researcher at the University of Aberdeen.

“Our taxes were paying, at least in part, to pay back that debt for almost 200 years,” said Mr Lee, who is researching Scottish people who travelled to the Caribbean and wrote about their encounters with slavery in the 1700s and 1800s.

He added: “That also means people who are of British-Caribbean descent, when they have been paying their taxes, have been paying back the money that was paid to the people who enslaved their ancestors.”

Fettercairn

Mr Lee said there is a simple answer to the question of how heavily the north-east of Scotland was involved in the slave trade: “Very”.

“Fettercairn was the heart of a slavery-based business empire in the 1800s,” said Mr Lee, giving one example of how much the trade in humans was embedded in the north-east.

The Shand brothers, John and William, owned and managed plantations in Jamaica.

At a parliamentary inquiry, William spoke of his interaction with hundreds of different plantations, each being worked by hundreds of slaves.

The pair travelled to and from their Fettercairn home and the West Indies over the years.

Mr Lee said: “In 1825, after John had died, William came back and he lived in a country house near Fettercairn. He ran his business empire from there in part. The business empire was very simple. Enslaved people on his plantations grew coffee, sugar and so on and it was taken from Jamaica and sold.

“It was sold as far away as Trieste on the Adriatic Coast of Italy and possibly even further east, to places like Greece.”

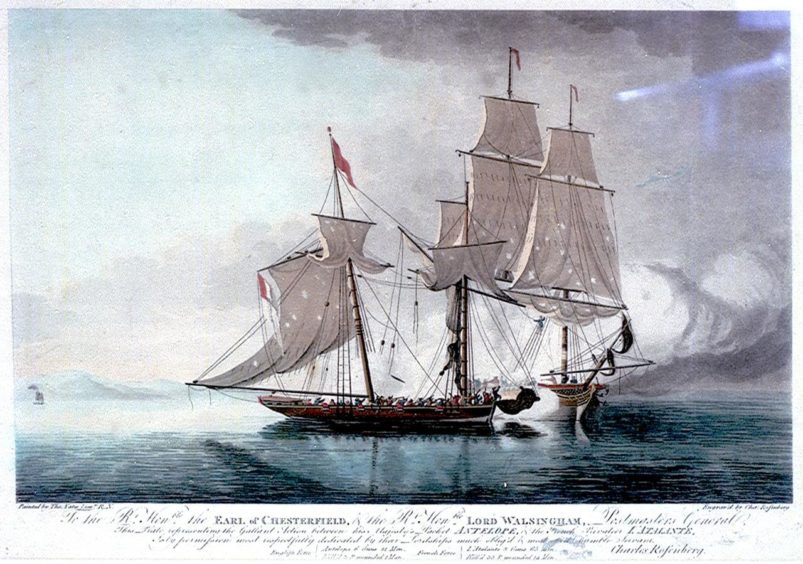

Other examples of Aberdeen’s involvement in the slave trade includes a letter in the archives dated 1717 from a ship called the Antelope sent from Jamaica.

It talks of kidnapping and enslaving people in West Africa before selling them in Kingston.

Others who profited included George Rainey from Sutherland.

Rainey, who died in 1863, received £50,000 in compensation for the loss of 1,000 slaves and a secondary claimant on a number of other properties.

He bought the islands of Raasay and Rona with the compensation money in 1845.

One of his policies in Raasay was to forbid his tenants to marry, a measure of control reminiscent of the slave plantations.

The trade was concealed because it often happened out of sight.

Ships would sail to Europe from places like Montrose and sell their goods before picking up slaves.

Ten would be chained together, fastened by the necks, hands and feet and marked with a burnt iron on the right hip.

Breeding machines

Slave ship sailors separated slave men from slave women and colonial gentlemen came on board and purchased the best looking girls.

The women were seen as breeding machines – producers of babies to become more slaves.

Many of Scotland’s country mansions also have links to slavery, including Aberlour House, in Moray, which was owned by Margaret MacPherson Grant, a philanthropist and sole heir to a plantation fortune.

Her uncle, Alexander Grant, amassed his wealth as a slave owner and sugar merchant in Jamaica and received £24,000 in compensation following the emancipation.

Inverness’s old infirmary and academy, along with Fortrose Academy, received money from the trade which operated in places like Grenada and the West Indies.

The Powis Gates, in Aberdeen, was built by Hugh Fraser Leslie in 1834 and features carvings of three black men which was a link to the family’s involvement in a grant of freedom made to their slaves in Jamaica.

Leslie, who died in 1873, owned several coffee plantations in Jamaica and the original construction at the Powis estate coincided with the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

Statues of those who profited still exist in the north-east including radical politician and slave owner George Kinloch in Dundee’s Albert Square and the Melville Monument on Dunmore Hill overlooking Comrie is dedicated to Henry Dundas who played a key role in delaying the abolition of the cruel trade.

Mr Lee said the north-east has a sizeable economic legacy from slave trade, including money from the slave trade flowing into the coffers of Marischal College and King’s College, which became Aberdeen University.

“What we do know is that profits that were generated in the Caribbean were sent back to Scotland and invested in railways, the cotton industry and so on,” he said.

“Money was moved from the Caribbean back to Britain and basically used, in part at least, to fund the Industrial Revolution. I see no particular reason why Aberdeen would have been immune from that process, but we need more research to be specific about that.”

However, while many people in the north-east were deeply involved in the slave trade, many were also involved in the campaign to abolish slavery, both prominent figures in the north-east and ordinary folk.

Recognition of the past

Mr Lee said: “There was an active abolitionist movement in the north-east of Scotland.

“Even by the standards of that time, people recognised that slavery was wrong. We are not imposing today’s morality on the past, we are actually holding people to the standards that were set at that time.”

Coming to terms with the legacy of slavery today can be uncomfortable, but Mr Lee believes it is something that needs to happen through recognition of the past and talking about it openly and learning more about it.

“The worst possible thing we can do is just not talk about it and pretend it never happened,” he said.

“Let’s have an open conversation about the past and how it has affected today. Let’s try and get justice and repair the damage that people in places like Aberdeen and the north-east did take part in – let’s be honest.”

When it comes to the current controversy over renaming streets or removing statues, Mr Lee believes there may be a compromise.

“Keep it as it is, but with lots of contextual information so when people walk down these streets, they actually realise what the history is.”

One very visible legacy of the slave trade is the redesign of Cluny Castle near Sauchen between 1836 and 1840.

Alexander Gordon of Cluny became very rich in Tobago before returning to London in 1790 and he left his estates to his nephews, including John Gordon (1776–1858) who received compensation as a slave-holder in 1834.

In 1838 he bought Barra from the bankrupt Macneills.

The Cruikshanks, farmers at Gorton (Grantown on Spey) rose from a modest background to make money in St Vincent and their legacy in Scotland includes two vast mansions – Stracathro (near Brechin) and Langley Park (Montrose).

Many works of fiction reference slavery but should they be banned?

Dr Kristen Treen, lecturer in American Literature at St Andrews University, believes such censorship should be challenged.

“I don’t think that banning or burning books is a useful response to the present situation,” she said.

“By banning books that promote values we would reject today, we lose an opportunity to learn from, and acknowledge, historical events that have shaped our society in the present.”

Gone with the Wind

Dr Treen believes fiction offers an important way of understanding the complexities and nuances of history.

“Fiction is never written in a vacuum, and as well as offering us insight into a number of different perspectives, fiction has a lot to tell us about the culture in which it was written at the moment it was written, its values and its conflicts. And it often prompts us to re-think, or question, or refine, our assumptions about the past.”

The film, Gone with the Wind, has been dropped on HBO Max as a result of its depiction of slavery and while this move has been criticised by many, calls are still being made to ban the book, published in 1936, from some corners.

“Mitchell’s representation of African-Americans in Gone With the Wind is riddled with stereotypes. Her representations of slavery are not realistic,” said Dr Treen.

“Like a lot of nostalgic literature which established the myth of the benevolent ‘Old South’ in the 1880s and 1890s, Mitchell romanticises the relationships between white enslavers and the African-Americans they enslaved.

“She portrays various versions of the ‘happy slave’, treated indulgently and kindly by their white ‘families’.

“These slaves are, more often than not, uninterested in the possibility of freedom and unwaveringly loyal to their enslavers.

“Elsewhere in the novel, Mitchell uses racist slurs and stereotypes to describe the bodies and actions of slaves, and perpetuates the stereotype of the violent, animalistic African-American man.”

Despite all this, Dr Treen doesn’t believe it should be banned.

“When read alongside other literature of the period which seeks to unmask the realities of slavery and the white system of oppression which upheld it, there is much we can learn from Mitchell’s novel about the workings of systemic racism in the American South; the kinds of rhetoric, reasoning, and violence which perpetuated it; and the ways in which these have shaped and influenced US society today.”

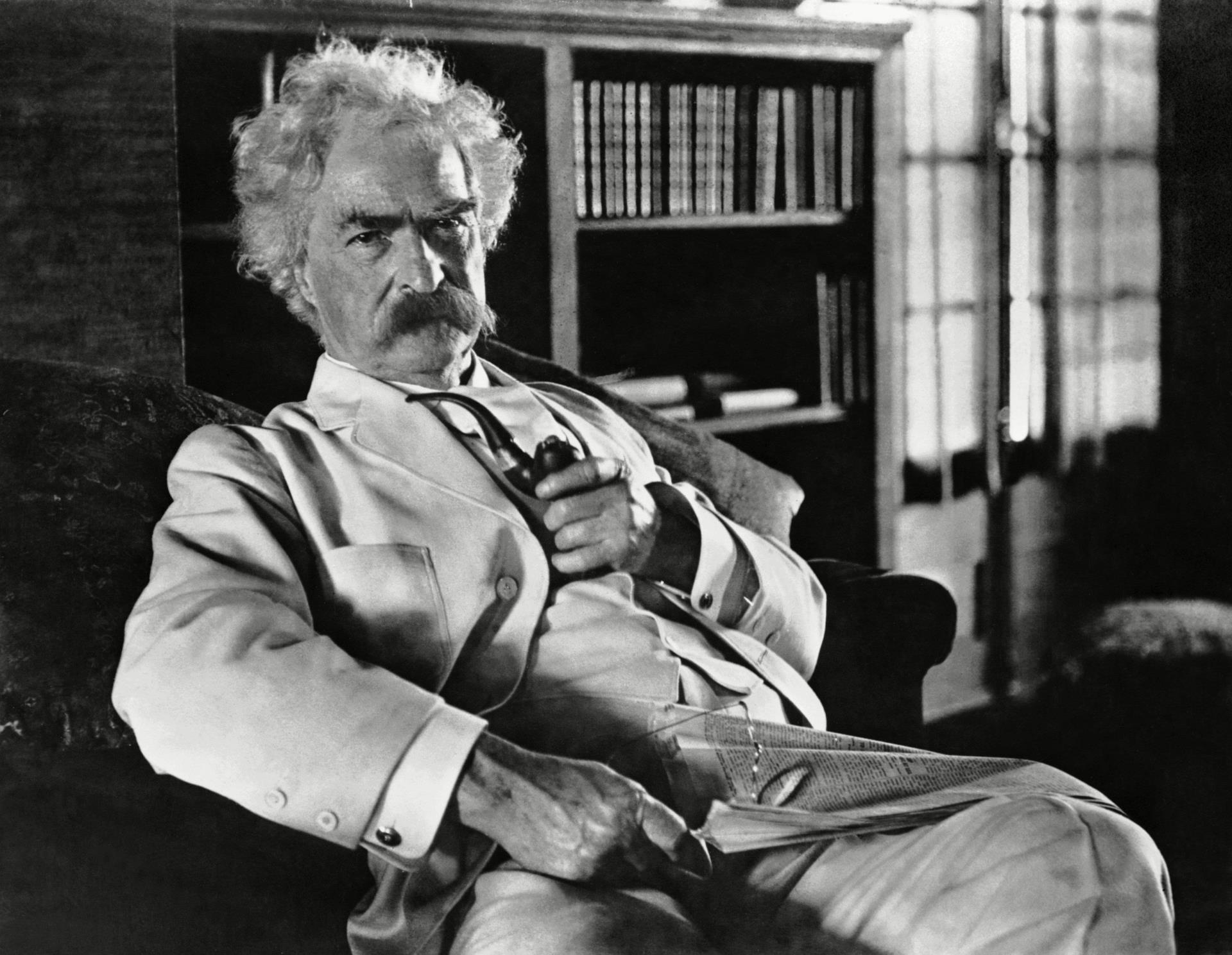

Another controversial novel is Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

There have been movements to have it removed from school syllabuses so that pupils aren’t subjected to the racial slurs used to describe the enslaved character, Jim.

“When discussing Twain’s novel with my undergraduates, I emphasise the fact that the novel often participates in racist representations of black characters, but also stress that there is much that we can learn about the nature of white racism during this period from Twain’s text,” said Dr Treen.

“This is something that the celebrated African-American author Toni Morrison argues too, and we read Twain in light of her analysis.”

“The story needs to be told”

Dr Lorna Burns, senior lecturer in postcolonial literatures at St Andrew University, agrees that banning books is “not useful” but understands there are demands to teach more writers of colour and, in the classroom, do more to explore the ways in which the colonial past and slavery is remembered through literature.

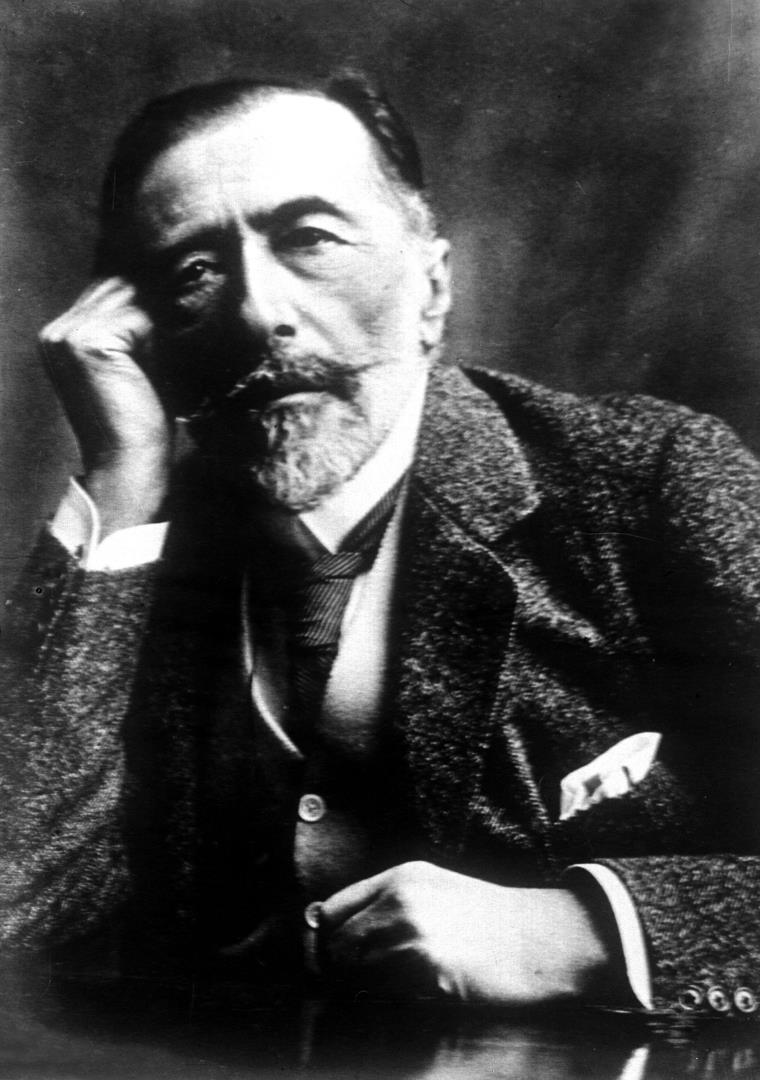

“Teaching a novel like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, for example, means asking students to read several passages in which African slaves are described in really problematic ways, as if they are less than human,” she said.

“I don’t think, though, that Heart of Darkness should be banned.

“What literature is really good at doing is presenting, within a single story, many different perspectives and points of view.

“It can also be provocative and encourage us to question what we think we know about the past.

“Charting history is a complicated process, because there is always another side to the story and sometimes those other perspectives have been overlooked or ignored. Fiction, I think, helps produce a more dynamic account of history.”

Dr Burns says that to censor books which reveal prejudices that we wouldn’t accept today means losing the opportunity to understand how such historical events came to be and their influence on shaping society in the present.

In his novel about the slave trade, Feeding the Ghosts, Fred D’Aguiar writes that ‘the past is laid to rest when it is told’.

“He wants to show us that telling difficult stories about our past is absolutely central to reconciliation and healing in the present, for all of us,” said Dr Burns.

“His aim in retelling a particular event in the history of slavery is to lay the past to rest, but in order to get to that point that story must be retold not just from the perspective of the masters but also the slaves.

“As his novel shows us, fiction is one way that we can retell history and so it has an important role in reconciliation even if it confronts us with uncomfortable facts.”

A Man’s a Man

National Bard Robert Burns was on the cusp of heading to Jamaica to be a “negro driver”, as he called it, in 1786 but the success of his poetry stopped him in his tracks.

“He was facing financial hardship at the time and so it was an opportunity for him to make something of himself,” explained Dr Burns.

“That same year he published his first collection, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, and it was so successful that he no longer needed to leave Scotland to make his fortune.

“It’s really interesting to think how different things might have turned out for the Bard.

“We can all wonder how his view of the world might have been slightly different.

“Would Burns the ‘negro driver’ have written A Man’s a Man for A’ That – a poem which celebrates our sense of common humanity and fraternity?”

It wasn’t an uncommon view at the time that the colonies could be an opportunity for individuals to make their fortune.

Another Scottish poet who made the journey that Burns abandoned was James Grainger.

He emigrated to the Caribbean island of St Kitts in 1759 where he married a wealthy heiress and became the manager of the family’s plantation.

“His poem The Sugar Cane offers advice on how best to cultivate the lucrative sugar cane, including the management of slaves,” said Dr Burns.

“It’s a poem that reveals the racist ideology of the period, but at the same time, it is one of the first examples of Caribbean literature.

“In that sense, despite the attitudes it reveals, it is important because it is part of the story of how Caribbean literature emerges and evolves.”

Turned a blind eye

Highlands-based historian David Alston believes we need to “read ourselves out of complacency and beyond our own comfort zone”.

“There is a danger that the current controversies over statues become a distraction from the real problem of racism in our society,” he said.

“The same can be said of ‘book wars’ – what to ban, what to promote? Instead I would ask: what do we have the courage to read?

“I have given a hundred or more talks on Scotland’s connections with slavery and it has struck me how easy it is for all of us to assume that we would have been among the abolitionists.

“But part of the tragedy of slavery is the way in which it permeated society.

“It sucked in so many people who collaborated in or turned a blind eye to these crimes.

“A meaningful concern for the future of humankind requires that we understand how, in the history of slavery, again and again ordinary people became the villains.”