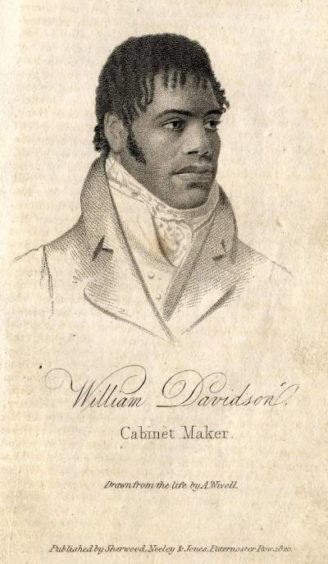

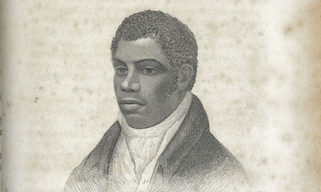

William Davidson, a black, radical revolutionary from the north-east of Scotland, was executed and publicly decapitated in 1820.

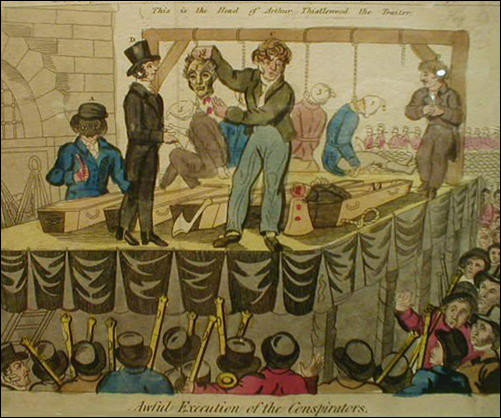

Davidson was one of five men hanged for treason outside Newgate Prison on May 1 1820, all having been convicted of plotting to kill the members of the British cabinet while they sat at dinner in the house of Lord Harrowby in Grosvenor Square.

Cato Street conspirators

They were known as the Cato Street conspirators because they had gathered in a rented loft in this street, near Lord Harrowby’s house.

The conspirators had despaired of bringing about serious constitutional change after the “Peterloo massacre” – the killing, in Manchester in August 1819, of peaceful demonstrators demanding parliamentary reform.

But they were also motivated by wider revolutionary aims, including the nationalisation of land, which had been promoted by the English radical Thomas Spence.

The five convicted men were all members of the Society of Spencean Philanthropists, formed after Spence’s death in 1814.

Despite its rather anodyne name it was a revolutionary organisation.

But they had, in fact, walked into a trap because the Society had been infiltrated by a Government agent – and the newspaper announcement of the dinner at Lord Harrowby’s was a hoax.

Half an hour after the men were hanged their bodies were cut down and a man in a black mask mounted the scaffold.

Using a knife, he decapitated the corpses.

Each head was passed to the assistant executioner who raised it up and made the formal proclamation, in this case: “This is the head of William Davidson — a traitor”.

This was the last occasion in Britain on which convicted criminals were publicly beheaded.

Gory detail

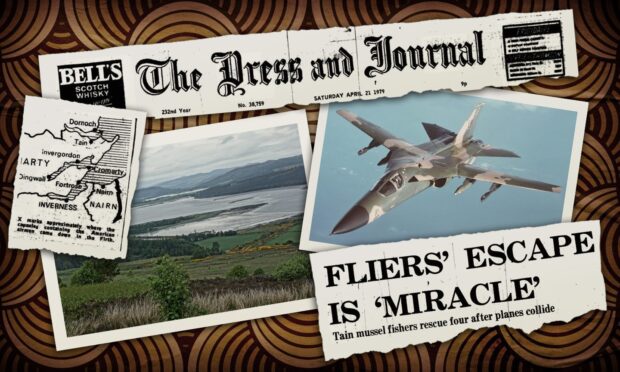

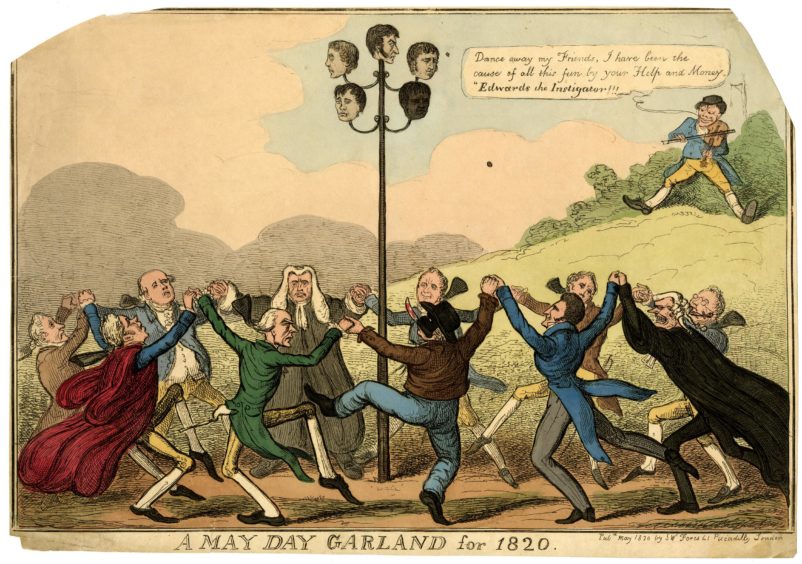

The newspapers reported the executions in gory detail and the artist Samuel Fores quickly produced and published a hand-coloured print: A Mayday Garland for 1820.

Part of the interest was in the fact that William Davidson was “a man of colour”.

Accounts of the trial and executions soon appeared in book form, with more details of the lives of the conspirators.

Davidson was said to be the second son of the Attorney General of Jamaica and a woman of colour.

The problem with this is that there was no Attorney General of Jamaica called Davidson.

So who was he?

Aberdeen connections

Dr David Alston, a Highlands-based historian and former councillor, takes up the story and said Davidson had a clear connection to Aberdeen.

One of the few character witnesses called at his trial was an architect who had known him there.

And in a letter to his wife from prison William told her that he was determined to maintain both his integrity and “that spirit maintained from my youth up” – a spirit which he described as having been “so long been in possession of the ancient name of Davidson (Aberdeen’s boast)”.

Dr Alston said: “Davidson described himself as ‘a stranger to England by birth’ whose father had been an ‘Englishman’ and whose grandfather had been a ‘Scotchman’.

“His use of the terms ‘England’ and ‘English’ can be confusing.

“He used them partly in accordance with the common convention by which ‘English’ might mean ‘British’ but also because he wanted to appeal to the English jury members’ sense of the ‘rights of an Englishman’.

“I believe that Davidson was probably the son of a Kingston merchant John Davidson, who was an assistant judge and was of sufficient status in the colony to be appointed in 1795 as Captain of the 1st Troop of Horse in the colony militia.

“This John Davidson had a clear link to the north-east of Scotland since he sent his son (also John Davidson) to Marischal College in Aberdeen for a single year in 1797.

“The only other Davidson from Aberdeen or Aberdeenshire who is known to have been in Jamaica lived a generation earlier – Charles Davidson, the second son of another John Davidson, in Tarland, 30 miles west of Aberdeen.

“A gravestone at Tarland of 1787 commemorates Charles as having died in Jamaica ‘some time ago’.

“It is possible that the Kingston merchant John Davidson was the son of this Charles Davidson – and this would be consistent with William Davidson describing his grandfather (Charles in Tarland) as a Scotchman but his father (John in Kingston) as an Englishman.”

William Davidson was born in Jamaica in 1786-87 to a free woman of colour who was herself wealthy enough to provide him, later in his life, with an allowance of two guineas a week and a gift of £1,200.

The allowance was paid “regularly through her agent” in England.

Dr Alston said William had been sent to school in Edinburgh at an early age, against the wishes of his mother, and later attended classes in mathematics in Aberdeen – although perhaps not at one of the university colleges.

He then became articled to a solicitor in Liverpool around 1802 but abandoned this circa 1805.

He tried to travel to Jamaica to visit his family but instead served six months impressed as a seaman in the Navy, perhaps in 1805, and then became apprentice to a cabinet maker in Liverpool in 1805-06.

After that he was employed as a journeyman cabinet-maker in Litchfield (Staffordshire) before setting up in business on his own account and failing.

He then moved to London where he became a journeyman cabinet maker again.

He set up in business once more in Walworth and in 1816 he married a widow with four children.

The couple had two children of their own and Davidson was an affectionate father whose main concern as he awaited trial was the welfare of his wife and all the children.

In his statement after being sentenced he said: “For my children only do I feel, and when I think of them I am deprived of utterance — I can say no more.”

Man of colour

Dr Alston said Davidson had twice suffered in his personal relationships because he was ‘a man of colour’, losing both a girl he planned to marry in Liverpool (who was spirited away by her friends) and a wealthy heiress, Miss Salt, in Litchfield (when the marriage was violently opposed by her father and she was unwilling to wait until she was 21).

When the second relationship ended he had tried to poison himself.

In London he became a Sunday school teacher but an approach to a young female teacher led to the claim, for which there is no evidence, that he “habitually indulged in attempts of a gross and indelicate nature on the persons of teachers and children”.

Nevertheless Davidson did not identify with other “men of colour” who he would hear referred to as his “countrymen” and during his trial he told the judge: “I never associated with men of colour, although one myself, because I always found them very ignorant”.

But another Afro-Scot from Jamaica, living in London, was Robert Wedderburn, one of the most prominent and best documented free men of colour in Britain at the time.

Dr Alston said: “He was born in Kingston, Jamaica, to Roseanna, an African-born enslaved woman, and James Wedderburn of Inveresk, near Edinburgh – and like Davidson he was a revolutionary follower of Thomas Spence, who he had met in 1812.

“As a young man Wedderburn came to London from Jamaica, where he worked as a tailor, became a Unitarian preacher, and adopted an increasingly radical creed.

“He first promoted his beliefs in his pamphlet The Axe Laid to the Root (1817).

“This made common cause between disadvantaged people in Britain and the West Indies and, using his own experience to validate his views, he called on enslaved Jamaicans to rise in rebellion.”

From his pulpit he cried: “Repent, ye Christians, for flogging my aged grandmother before my face” and in his pamphlet addressed planters like his father: “Taking your Negro wenches to your adulterous bed…What do you deserve at my hands? Your crimes will be visited on your legitimate offspring.”

Horrors of slavery

In a later pamphlet, The Horrors of Slavery, he described his only visit to Inveresk.

“I visited my father, who had the inhumanity to threaten to send me to gaol if I troubled him. He did not deny me to be his son, but called me a lazy fellow and said he would do nothing for me. From his cook I had one draught of small beer, and his footman gave me a cracked sixpence.”

Had he not been arrested and imported waiting trial on a charge of blasphemous libel in January 1820, Wedderburn would also have been among the Cato Street conspirators.

Dr Alston said: “Sadly for Davidson, another radical Richard Carlile, also then in prison, had suspected Davidson himself of being a government spy and agent provocateur.

“Davidson had offered to spring Carlile from jail ‘with 60 or 70 men of the same mind’.

“After Davidson was hanged and beheaded Carlile sent £2 to assist his widow, Sarah Davidson, and wrote a public letter of apology.”

It stated: “Be assured that the heroic manner in which your husband and his companions met their fate, will in a few years, perhaps in a few months, stamp their names as patriots, and men who had nothing but their country’s well at heart.”

Dr Alston said William Davidson and Robert Wedderburn both experienced prejudice and rejection in Britain because of their African origins.

He said both turned to revolutionary politics which they saw as the only ways of righting the wrongs they saw in society.

Although personally proud to be a Davidson and singing “Scots Wha Hae” as he was arrested, William had no apparent connection to or support from relations in Aberdeen.

He had left the town abruptly about 1801.

Dr Alston added: “If my identification of his family is correct then, by the time of his trial, his uncle Duncan Davidson was a prominent advocate in Aberdeen and William would have been a dangerous relation to acknowledge – but that cannot have been true when he was a boy of 14.”