There were some people who thought he might not be around to celebrate his 75th birthday, but Ken Buchanan has always been a resilient character, in and out of the boxing ring.

The body might be less robust than it used to be, but his eyes remain focused and purposeful.

Stare into them, and you can discern the spirit of a man who reigned supreme across the globe 50 years ago and understand why his reputation is so exalted in the sport’s International Hall of Fame.

Five decades may have passed since the wiry, indefatigable competitor travelled to Puerto Rico, where he defeated Ismael Laguna, the world lightweight champion from Panama.

Yet although many experts believed San Juan’s warm weather would affect Buchanan, he always believed in his own abilities once the bell had tolled and beat Laguna in a brutal battle of wills to become the king of the world.

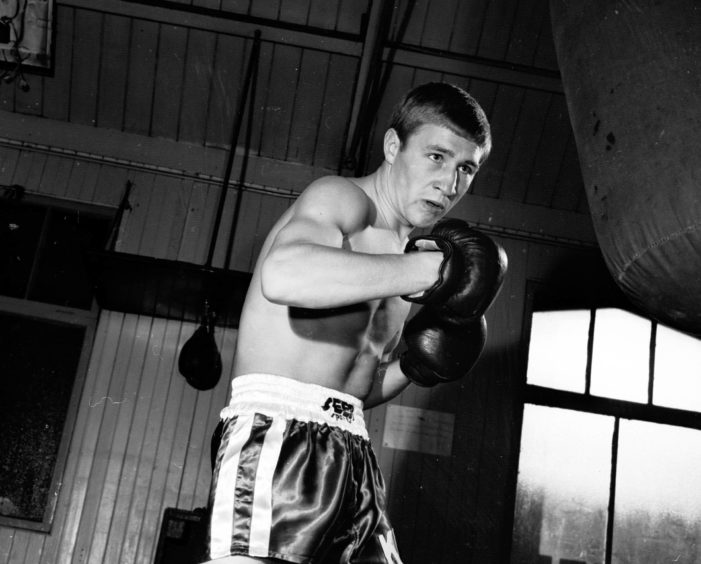

It was the crowning moment of a pugilistic career which began on a summer’s afternoon in 1953 when his father, Tommy, took him to see the Joe Louis Story at an Edinburgh cinema.

At eight years old and a mere three stone and two pounds, the kid was soon entreating his dad to buy him a pair of boxing gloves and his ceaseless cajoling eventually paid dividends.

He told me: “I would badger him and pester him, but he kept stalling, so I had to use a different strategy.

“I waited until one of his pals was talking to him in the garden, then I dashed up to him and shouted: ‘Dad, dad, are you going to teach me how to box?’

“He looked at me with irritation, and replied: ‘Aye, but just wait a while.’

“I answered back immediately: ‘No, no, you have to promise,’ and out of sheer exasperation, he said: ‘Okay, I promise’ in front of another person.

“So that was me settled, and we went down to the Sparta Club in the next couple of days. I loved it, you know. Sure, I was a dunce at school, but once I had slipped the gloves on, I was an equal for anybody.”

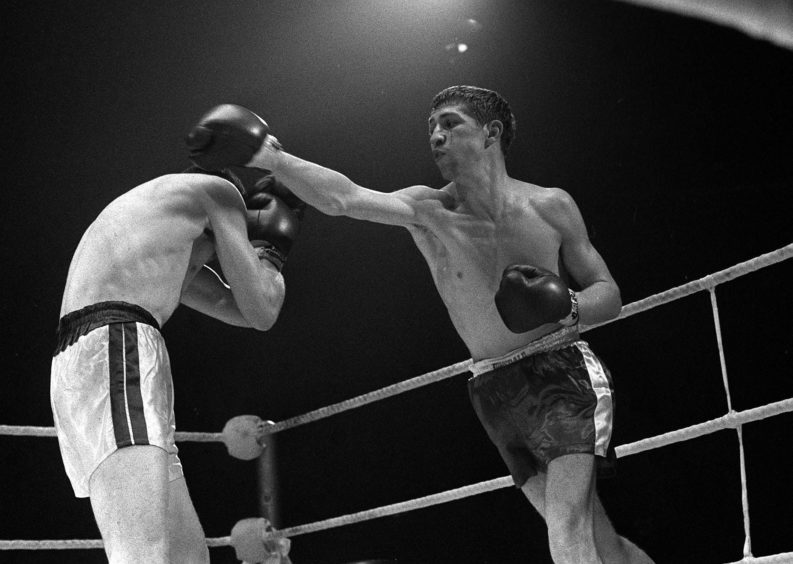

That much was unarguable during a halcyon period from 1970-75 when nothing, be it partisan officials, riotous foreign fans or dishonest antagonists, could prevent Buchanan from feasting on a rich diet of honours and baubles.

Whether overcoming midday temperatures in excess of 100 degrees to best Laguna, or trouncing the WBC numero uno Ruben Navarro in Los Angeles five months later, there was an unstinting dedication in his disposal of rivals such as Donato Paduano, Mando Ramos and Carlos Hernandez.

That was in the build-up to one of the most famous and notorious tussles in fistic history at Madison Square Garden, where Buchanan, pitted against the Panamanian Roberto Duran, nicknamed ‘The Hands Of Stone’, competed so perseveringly and courageously that the South American eventually rammed his knee into the groin of his adversary, leaving him unable to continue amid bedlam from all quarters.

To many of the throng, it was a blatant transgression, but Buchanan has grown accustomed to dealing with life’s slings and arrows and occasional low blows.

He added: “It still rankles with me, of course it does. Duran robbed me. He attacked me after the bell, and should have been disqualified. I could have gone on, even though the pain was indescribable, but the referee was having none of it.

“Ach, it’s a hell of a long time ago now, but it still hurts. It had been bloody hard graft seizing the world championship from Laguna in San Juan and holding on to it for two years, because don’t forget this was at a stage when any one of half-a-dozen guys would have been good enough to win a world title today.

“But, on the other hand, there were great times and a stack of tremendous stories to put next to the disappointments.

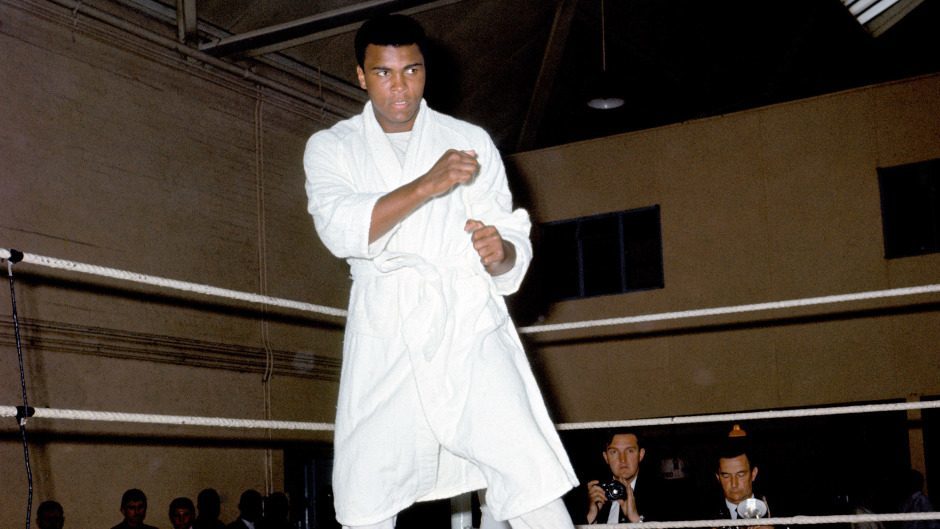

“I mean, there was one occasion when I met Muhammad Ali in New York in 1970, and we shared a room together before the fight. You know how? Well, whilst we were at the weigh-in, Angelo Dundee came up to me and said: ‘Ken, is it okay if Ali shares your dressing-room?’

“Think about it. Here was me, this wee laddie from Dalkeith, and I’m getting asked for a favour by the trainer of the greatest fighter who has ever lived.

“I said to Dundee: ‘You’re only kidding, right?’ But no, he was deadly serious, and Ali and I swapped banter and jokes and warmed up together prior to our contests.

“Memories are made of these moments.

“I guess now that, in retrospect, I didn’t realise how fortunate I was in my youth, but that’s not uncommon, is it?

“There was also one night in 1971 when I was named the British Sportsman of the Year – Princess Anne collected the women’s award – and the pair of us had to dance together at the dinner.

“Anyhow, I’d gone to lessons for three months – my dad was a terrific dancer – and I thought I would be a natural, but I wasn’t. In fact, I was more nervous than I had ever been before walking on to the floor.

“But, like a fool, I found myself telling the princess: ‘Don’t worry, hen, dancing is in my blood.’

“Well, after a couple of minutes shuffling around with not a shred of co-ordination, she spoke through clenched teeth: ‘You must have a circulation problem then because it hasn’t reached your feet.’

“That was me stymied – after all, what could I say to royalty?”

In these balmy yesterdays, cash was flowing into Buchanan’s coffers and vanishing with equal speed.

His buddies, the kind of shysters who would steal the ornaments off their granny’s mantelpiece, slapped him on the back and supped deep on his largesse and naivete.

On and on it rolled, this giddy gravy train, until the inevitable decline commenced. Buchanan lost a fraction of his sharpness and gradually, inexorably, his lustre vanished along with his supposed drinking acquaintances.

He told me, with a quiet twinge of regret: “There’s no question about it, if I could change things, I would do so, but there’s no use dwelling on what might have been.

“By the end of the 1970s, the papers regularly carried pieces claiming that I was a washed-up has-been, down on my luck, and I reached the point where I would tell the journalists: ‘Ach, write what you want. If you believe I’m a down-and-out, then go ahead, stick it all down.’

“Yet, let’s be honest, you can’t be the world champion for ever, and it had to come to a full stop. If it hadn’t been Duran booting me you know where, Father Time would have done the same thing, sooner or later, wouldn’t he?

“At least, I didn’t wind up like Ali. I’d heard stories that his illness was really bad, but when I watched this giant of a man reduced to shambling into the Waterstones shop (in Edinburgh in the early 1990s) with no idea where he was, it was more than I could stand.

“I had to leave the store and dash away because I was greetin’ my eyes out at the state he was in. It dragged me back to that scrap he had with George Foreman (in 1974), where he took punch after punch on the ropes.

“It was the sort of fight the authorities shouldn’t have permitted to continue – and was pummelled beyond any reasonable bounds. (Even though Ali finally triumphed).

“Genuinely, I think he suffered a dreadful amount of damage that night because he wasn’t a moving target: he was a human punchbag, and the cells in his brain must have been obliterated. They must have been.”

Given the gravity of Buchanan’s tone, one might envisage he would have some sympathy for boxing’s critics and abolitionists, but despite the evidence of his own eyes, he defends the noble art to the nth degree.

Yes, he may tell you, you don’t know what it’s like to feel frightened or find that bitter taste in your mouth, until you have squared up to your enemy and discovered he is better than you – “you’re telling yourself this isn’t happening, and that you’ll wake up from the nightmare, but it is happening and you feel sick at the thought”.

But even as Buchanan meditated on the shroud of fear which habitually hangs over his business, there was a spark in his eyes and a steely recollection of the primeval nature of the business in which he earned his place in the pantheon.

“The ring is the loneliest place in the world to be, especially when your opponent is battering the stuffing out of you and the referee’s not bothering his backside” he said.

“But you can’t ban boxing because it’s man’s first sport. From the minute you are born, you’re fighting…for air, for water, for food, everything. So, regardless of the risks, there will always be guys like me in love with the game.”

The ultimate irony, that where Buchanan could evade the punishment of boxing’s meanest practitioners and emerge triumphant, yet struggle so badly in his jousts with Old Father Time, has not escaped him.

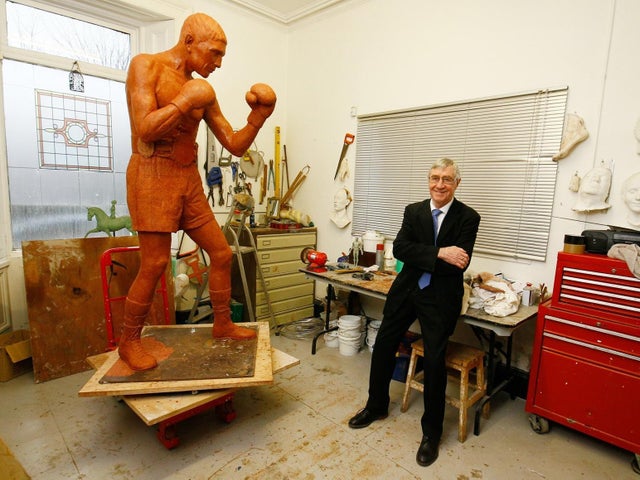

But at least he has found a new audience for his pyrotechnics, been rediscovered by his native city and there’s a statue now of Buchanan in Edinburgh and paintings and other pieces of memorabilia harking back to his halcyon days.

He has had to grapple with his own private demons, and acknowledge his frailties away from the gym, but this redoubtable fellow has rolled with the punches wherever he has travelled and his story is worthy of a Hollywood script.

And he can still laugh at treading on the toes of a princess!

A brief look at Buchanan’s feats

Ken Buchanan’s achievements speak for themselves. The undefeated British lightweight champion from 1968 to 1971, world lightweight champion from 1970-72 and European title-holder from 1974-75, was presented with numerous awards by the notoriously hard-to-please American press corps and was voted Britain’s Sportsman of the Year in 1971 as well as collecting an MBE for his services to boxing.

Buchanan also became the only living Scot to be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, near New York, at a glittering ceremony in 1998.

The Edinburgh man attended the festivities in the company of a list of other distinguished fighters such as “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler, Sugar Ray Leonard and Joe Frazier.

Even now, more than 40 years after he retired from the ring, Buchanan remains one of his country’s most famous and enduring sports personalities.

Indeed, according to the boxing historian, Brian Donald: “His talents were unique enough to make him Scotland’s greatest-ever fistic champion.

“And he was among the most accomplished and courageous British fighters who has ever travelled to foreign rings.”