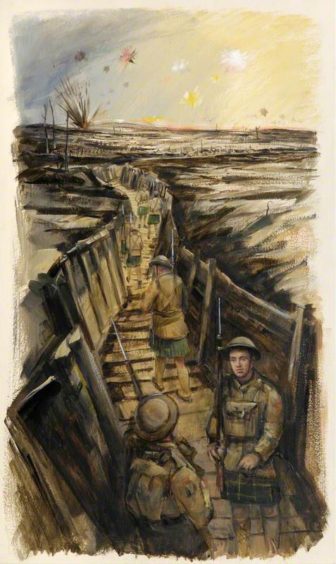

The realities of life in the trenches were all too clearly highlighted during this year’s blockbuster film 1917.

There was no end to the privations for the legions of young soldiers who sustained injuries during the Great War, whether from enemy fire or the all-encompassing mud which surrounded them for months and often years as the hostilities raged on.

Many succumbed to sepsis, and the mud and dirt which pervaded the conflict often meant that troops perished from apparently innocuous wounds.

However, one pioneering surgeon from Aberdeen did his utmost to transform the situation and ended up making a huge difference to the lives of thousands of casualties.

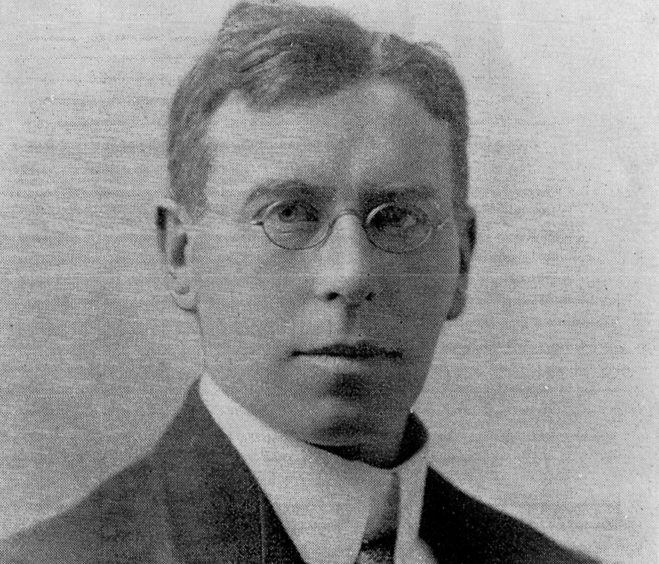

His name was Henry Gray, and his biographer Tom Scotland – another medical man from the Granite City – is working hard to make him better known in his homeland.

It has become almost a crusade for the retired orthopaedic surgeon, who has spent much of the last decade researching and writing a book in association with Ann Boyer, the great-niece of the distinguished north-east surgeon, who died in 1938.

And he told the Press and Journal why it was important that a new generation of Scots commemorate the achievements of one of the great unsung heroes from a century ago.

Mr Scotland said: “In 1914, surgical methods were hopelessly inadequate. Soldiers with filthy contaminated wounds had antiseptic dressings applied before being sent by hospital train to base hospitals on or near the French coast for definitive surgery.

“The journey took far too long and, even while they waited, thousands of men succumbed to overwhelming septic wound infections and to gas gangrene.

“Gray pioneered wound excision, which is the early radical removal of all dead tissue and contaminated tissue from wounds, and the removal of clothing and metallic fragments and the conversion of a filthy contaminated wound to a clean one.

“Urgent limb and life-saving surgery was performed at casualty clearing stations, which were much closer to the front than they had previously been.

“Effective surgery was delivered much sooner, significantly reducing the incidence of lethal wound infections and thousands of lives were saved as a consequence.

“One of the worst wounds was the compound fracture of the femur (thigh bone) caused by gunshot or shell fragment.

“The percentage mortality in 1914 and 1915 was 80% because hopeless splintage of fractures resulted in excessive bleeding.

“Patients arrived at clearing stations in shock due to blood loss and they were unable to withstand wound excision to save their limbs and lives.

“In 1917, Gray ensured that all cases of compound gunshot fractures of the femur were immobilised much more effectively in a Thomas Splint.

“Most patients arrived in good clinical condition and were fit enough to undergo wound excision. Mortality was reduced to less than 20%.”

It was a story which couldn’t be reported at the time. And that was to become one of the enduring themes of Gray’s life.

Mr Gray also opened a centre in 1917 to promote research into clinical shock, which was a major killer at the time. He was also an early advocate of blood transfusions and excelled in inspiring those around him to work hard even when they were exhausted.

The north-east trailblazer was an authority on infections and was experienced in the management of gunshot wounds of the head and spinal cord.

According to the work which has been carried out by Mr Scotland, his compatriot thrived on the philosophy that genius was an infinite capacity for taking pains.

He watched aghast as so many youngsters, thrust into battle for the first time in their existence, were mowed down as much by germs as German artillery and mines.

Mr Gray even removed a bullet from the heart of a patient under local anaesthetic and his work was given widespread acclaim from Australian and New Zealand medical officers, which led to him receiving special mention in their official medical histories.

He was admired by the many young surgeons who toiled at the front because he made it clear that he appreciated their exertions.

They, in return, held a special dinner in London to acknowledge his achievements during the war.

Camaraderie and comradeship was evident amid the carnage.

Mr Scotland has closely studied his subject and has no doubt that this resolute and tenacious character was far happier working in the field and adopting a hands-on approach to his vocation than following the example of some of his contemporaries and staying detached at a safe distance from the horrors of war.

He said: “Henry Gray had strong principles and always put his patients first.

“He expected his team to do likewise. He was extremely supportive of young surgeons working in casualty clearing stations and was much admired by them.

“He was always in the thick of things when there were many casualties from a battle.

“But he got on less well with his contemporaries and he could be prickly. Some accused him of being too arbitrary and dictatorial.”

Nonetheless, his labours led to him receiving a knighthood and he continued to devise new means of tending to the sick and wounded throughout his life.

His biographer said: “Gray made enormous contributions to war surgery during three and a half years which he spent in France.

“He was mentioned in dispatches five times, he gained a knighthood for his services to war surgery, and he was subsequently awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Letters by Aberdeen University.

“There were many things which he did to help those in need and yet hardly anyone knows his name in his home city. I want to make people aware of this great surgeon.

”He was an extraordinary figure and he made a huge difference to so many.”

Henry Gray’s early life

Henry McIlltree Williamson Gray was born in Aberdeen on March 14 1870 and was the fifth child of Alexander Reith Gray and Barbara Shand Anderson.

He attended Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh and studied medicine at Aberdeen University, subsequently graduating with honours in 1895.

After serving as house surgeon to Sir Alexander Ogston, professor of surgery at the university, he studied in Germany for 18 months where he learned the techniques of aseptic surgery.

He introduced this in Aberdeen when he became a consultant surgeon in the city in 1904 and he was constantly searching for new ways of tackling infection and disease.

In the years leading up to the war, he established himself as a surgeon of outstanding ability who set himself very high standards and expected others to follow suit.

In addition to being credited with bringing aseptic surgery to Aberdeen, he was instrumental in introducing local anaesthesia to surgery in Britain.

And that development, in itself, transformed the way operations were carried out.

Yet, although Mr Gray returned to Aberdeen after the war, he was unable to settle back into his former environs.

He was offered, and accepted, the position of surgeon-in-chief to the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal.

But, when he travelled to Canada, he gradually became involved in bitter political infighting between Sir Arthur Currie, principal and vice-chancellor of McGill University and Sir Henry Vincent Meredith, president of the RVH, over the issue of whether Gray should be offered the chair of surgery at McGill University.

It was one of those academic debates which made virtually no impression on the wider world, but had a seismic impact on the individuals involved.

Ultimately, rather than furthering his prospects, the move to Montreal destroyed him professionally and he lived out the rest of his life in surgical obscurity.

He died in Montreal in 1938. And, for many decades thereafter, his achievements were almost forgotten about.

The tragic letter which spurred on Gray

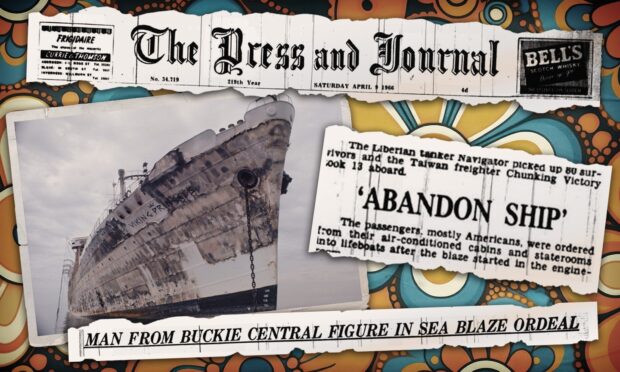

There are precious few artefacts left behind of the work which was carried out by Henry Gray and his colleagues in the trenches during the First World War.

But one item which has survived is a letter which was written by him to his sister Eva and it highlights the desperate circumstances which surrounded these medical staff.

The correspondence was penned from a base hospital in Rouen in 1916 and it happened in the most poignant of circumstances.

Mr Gray’s brother John had just been killed in Mesopotamia and the surgeon was commiserating with Eva at the same time as telling her about the litany of awful things which he had to deal with on a daily basis throughout the hostilities.

He said: “Damn this war. It gets on my nerves so much, going round as I do and seeing the very worst cases.”

He resolved to act to improve the situation and it was a cause to which he devoted himself for much of the rest of his life.

History will record that he achieved his goal with a positive impact for so many stricken men on the front line – and that pioneering work explains why Mr Scotland has done his utmost to urge greater recognition for this driven individual.