What would it be like to be stranded on a desert island and watch, as the years passed, some 20 to 30 ships sail by without stopping?

On October 16 1847, a party of sailors from HMS Rattlesnake went ashore at Cape York, Queensland, on Australia’s far north-eastern tip, and passed an aborigine on the beach without giving her a second glance.

They turned when she called to them in English. “I am a white woman, why do you leave me?” she said.

Scrutinising her “dirty and wretched appearance” more closely, they realised they were looking at someone who had been marooned here for quite some time. What they didn’t appreciate was her fear that the aborigines she had fled from would appear at any moment bent on getting her back.

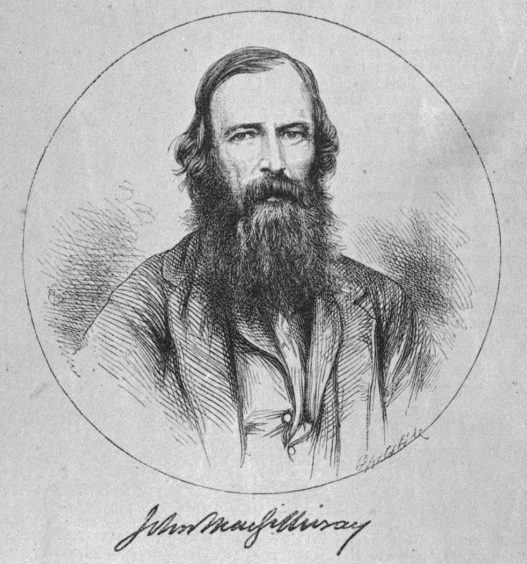

This “startling incident” was recorded by the ship’s 26-year-old naturalist, John MacGillivray, whose job was to document fauna and flora, not a near-naked woman who “wore no clothing with the exception of a narrow fringe of leaves in front, her skin tanned and blistered with the sun” and who was not only British but came from the same part of Scotland that MacGillivray did – Aberdeen.

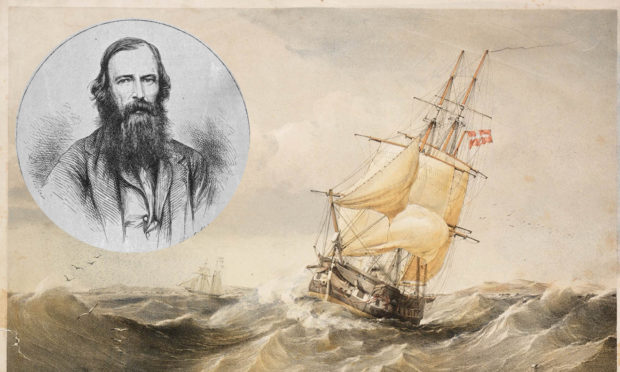

It was a surveying mission that HMS Rattlesnake, commanded by Captain Owen Stanley, had been sent on by the Admiralty, whose instructions, ironically, included: “You will take care never to be surprised.”

They were to find a safe route around the top of Australia, through Torres Strait, for homecoming ships. Accompanied by the Bramble, and carrying 180 officers and men, the two ships had left Plymouth on December 11 1846. They were also instructed to take £50,000 (well over £1 million today) to the Cape of Good Hope, and £15,000 of treasure to Mauritius, a British colony since 1810 when they’d grabbed it from the French.

John MacGillivray was born on December 18 1821 in Aberdeen, the oldest of 12 children. His father, William, was a famous British ornithologist and regius professor of natural history at Marischal College, Aberdeen.

Studying medicine in Edinburgh, and before graduating, MacGillivray was appointed by the 13th earl of Derby as naturalist with HMS Fly, on which he spent three years surveying the coasts of Australia and New Guinea.

His record of events of the voyage he was on now, Narrative of the Voyage of HMS Rattlesnake, was published in 1852. After crossing the Atlantic, MacGillivray witnessed slavery in Rio despite its having been abolished in 1835: “The frequency of iron collars round the neck, and even masks of tin, concealing the lower part of the face, and secured behind with a padlock, would seem to indicate extreme brutality.”

Arriving in Hobart Town in June 1847, they sailed up Australia’s east coast and by August made contact with aborigines on the 19×4-mile sand-hill called Moreton Island, off the south-eastern Queensland coast. Their meeting with the aborigines there demonstrates how delicately balanced – and potentially volatile – rapport between two totally different cultures in that era could be: “Although these natives had had much intercourse with Europeans,” wrote MacGillivray, referring to the “friendly communication” between them, “a party of them who came on board could not be persuaded to go below; and one strong fellow (One-eye, as he called himself) actually trembled with fear when I laid hold of him by the arm to lead him down.”

One day, their ship was attacked: “Their first act was to throw into the cabin some lighted bark,” he wrote, “and when the master and one of the crew rushed on deck in a state of confusion, they were instantly knocked on the head with boomerangs and rendered insensible.” But another sailor arrived and chased the aborigines off with a sword.

MacGillivray documented 41 marine species previously unknown to science.

While fishing for mullet and bream, they also came across the ultimate predator: “Sharks of enormous size appeared to be common. One day we caught two, and while the first taken was hanging under the ship’s stern, others repeated attacks upon it, raising their heads partially out of the water, and tearing off long strips of the flesh before the creature was dead.”

They landed on Eagle Island, named by Captain Cook who’d found a giant nest there and written: “It was built with sticks upon the ground, and was no less than 26 feet (8m) in circumference, and 2’8” (2m) high,” MacGillivray adding that he and Mr Gould were sure they were “the work of the large fishing-eagle of Australia”.

MacGillivray’s wit was never far away: “One of the boat’s crew, not over-stocked with brains, during his rambles picked up a human skull with portions of the flesh adhering.” The sailor had thrown it into the sea even though a European hut was found along with clothing, shoes, tobacco and bits of a whaleboat. Had this been another Robinson Crusoe?

But that was forgotten now that MacGillivray and the others had encountered an actual castaway, 21-year-old Barbara Thomson who, four or five years before, was the sole survivor of a shipwreck near Prince of Wales Island, off Cape York, after travelling with her husband in his cutter.

He was about to find out that she had been rescued by aborigines in a canoe who took her to another island (Muralug) where one of them, called Boroto, as MacGillivray later wrote in his diary, “took possession of (her) as his share of the plunder; she was compelled to live with him, but was well treated by all the men, although many of the women, jealous of the attention shown her, for a long time evinced anything but kindness.”

Always closely watched by the aborigines, Barbara was used to seeing ships passing only two miles away and assumed that a chance of escape would never come. But when she had seen the Rattlesnake actually moor in a mainland bay, the temptation was too great. She persuaded some closer aboriginal friends to take her towards the ship, MacGillivray writing: “The blacks were credulous enough to believe that as she had been so long with them, and had been so well treated, she did not intend to leave them – only she felt a strong desire to see the white people once more and shake hands with them (and) procure some axes, knives, tobacco, and other much prized articles… After landing at the sandy bay on the western side of Cape York, she hurried across to Evans Bay, as quickly as her lameness would allow, fearful that the blacks might change their mind; and well it was that she did so, as a small party of men followed to detain her, but arrived too late.”

Three of them – the ones who had saved her from the shipwreck – were allowed on board at Barbara’s own request, where they were presented with an axe each and other presents. They would have known by now that Barbara had just turned the tables on them, and that she had used the same tactics that they’d been using on her for years to keep her. But, although she had successfully freed herself, would she stay? After all, she had been part of an aboriginal family for a long time. Perhaps she would change her mind now and remain with them.

The British officers didn’t know what to think. Not hearing her speak immediately, the possibility would have dawned on MacGillivray and the others, who by now were probably all spellbound enough, that this white woman – marooned for so long – might have forgotten how to speak English altogether.

“Asked by Captain Stanley whether she preferred remaining with us to accompanying the natives back… she was so agitated… making use of scraps of English alternately with Kowrarega language, and then… not understood, the poor creature blushed all over, and… beat her forehead with her hand, as if to assist in collecting her scattered thoughts,” wrote MacGillivray. “At length… she found words: ‘Sir, I am a Christian, and would rather go back to my own friends’.”

Boroto was allowed aboard with gifts of fish and turtle, but “after in vain attempting by smooth words… to induce her to go back and live with him, left the ship in a rage (and) threatened that, should he… ever catch his faithless wife on shore, they would take off her head.”

Needless to say, she stayed on the boat, was “very soon restored (to) health and… eventually handed over to her parents in Sydney”.

The Rattlesnake arrived back in England in 1850, MacGillivary migrating to Australia in 1864 where, on June 6 1867, he died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 45.

One can only wonder if Barbara Thomson ever visited his huge collection of birds, mollusc shells and plants – that today still reside in places such as the British Museum and Kew Herbarium – and saw all the other things that had been washed up on the beach.