Curfews and threats of cancelling Christmas at a time of national crisis? Been there, done that, got the T-shirt.

These days the storm and drama that broke out when I was a 12-year-old is all but forgotten, except in a “do you remember when we had power cuts” sort of way.

It was the early 70s and suddenly, without any warning, all the lights would go out and the telly would fade to that wee white dot that lingered for a while after you unplugged it.

Not just in our house, but every flat in the stair, every stair on the street, every street around our end of Edinburgh. Street lights, too. Nothing outside but the odd headlights of cars going past.

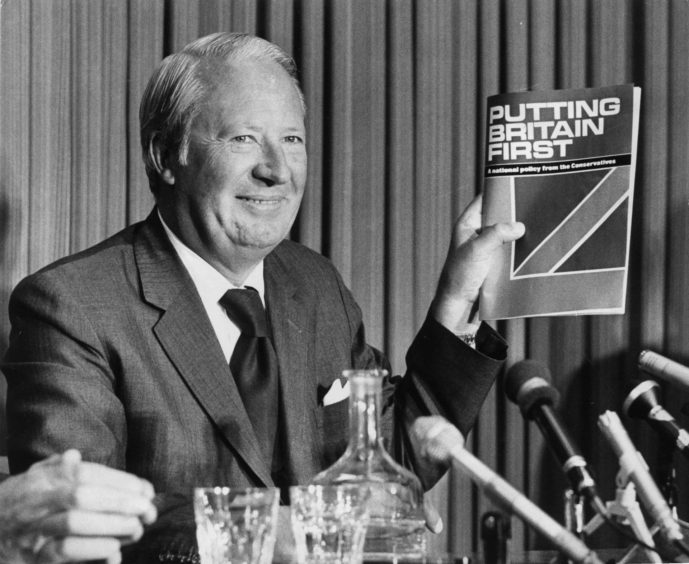

This was the era of war in the Middle East and long-running miners’ strikes that forced Edward Heath’s government to switch off the leccie to ration it. And here’s a three-day week for the nation while we’re at it.

I remember the first time the world went dark in 1972, with all the mines shut down and coal stocks depleted. Back then it was a bit random when you would be plunged into the gloom. Your lights would flicker a bit, dull down to brown then just go off.

However, the blackouts of 1972 were just a warm up for what followed in 1973. Not only did we have miners gearing up for another strike, starting with an overtime ban, but electricity workers had joined them. Then there was the small matter of war in the Middle East that had disrupted the flow of oil, sending prices soaring and supplies dwindling.

State of emergency

With that double whammy, Ted Heath got serious. The restrictions brought in makes the coronavirus restrictions look like a walk in the park.

With the government declaring a state of emergency, petrol was rationed, the use of electricity for floodlight, heating shops, offices and restaurants was banned. This was in November, remember, back in the day when winters were properly cold.

That was just our starter for 10. By December the speed limit was slashed to 50mph to save fuel, everyone was asked to save electricity (bathing together became a thing) and telly was shut down at 10.30pm – except at Christmas.

And if that wasn’t enough, the three-day week came into being – restricting the opening of all but essential services. Aye, it was the Covid-19 response on steroids. And the power cuts were back.

Now, I would like to think that panic buying is a modern phenomenon, driven by halfwits on social media who think an outbreak of coronavirus is just reason to buy all the bog roll and dried pasta you can get your hands on.

But even without the power of Twitter, the power cuts of the early 70s saw a shortage of candles, while stores were selling out of paraffin lamps. Some butchers turned entrepreneur and made candles out of string and animal fat. It was a heady mix of stench and fire hazard.

Absolute indifference

How did I respond to all that drama and unrest in a world teetering on the brink? With absolute indifference.

To be frank, I didn’t have a clue what was going on or why. I was aware this was a “Big Deal” by the serious sounding newsreaders – and the level of jokes being made about it by Mike Yarwood and Bruce Forsyth.

Personally, I just thought it was all rather exciting when the lights flickered out and we had to break out the candles and board games. This was when I learned that a game of Snap could quickly become a combat sport among bored siblings. I also realised that Monopoly was staggeringly boring.

That said, I developed new skills. I worked out how to rig a bulb to one of those big box-like batteries to create a makeshift electric lantern. Sure, I could have used a torch, but where’s the fun in that? I also became a dab hand at making toast on the coal fire with a long fork.

Some people have memories of this as a time when families sat around and talked to each other. I just remember sitting behind the couch with my bulb and battery devouring as many books as I could get my hands on, half listening to squabbling over who put the hotel on Mayfair and no, you can’t keep a get out of jail free card once you’ve played it.

By the time the power cuts of 1973 rolled around, random blackouts were a thing of the past. Instead newspapers carried a timetable of which areas would lose power and when, so you could prepare. (I always wondered if that was a charter for the shoplifters to make sure they were in Woolworths when the lights went out).

Community spirit had kicked in from the outset. Everyone in our stair kept an eye out for each other and checked on the wee old lady who lived on the ground floor on her own. There was an elderly family friend of ours who lived a couple of streets away and it was my job to chap her door on the way home from school to make sure she didn’t need any messages.

What I don’t remember is moaning and whinging becoming a national pastime. But then, I wasn’t being drip-fed nonsense via a screen. If I wanted to see what people thought about things, I’d have to read the letters page of the paper. Which I didn’t. I was 12 and allowed to get on with being a kid.

However, there are lessons to be learned from those dark days of the early 70s.

At the time, it was grimness on a plate and things looked brutally bleak.

Today, it is scarcely on anyone’s radar beyond an almost folk memory of the lights going out every so often.

One day, we will look at the current coronavirus the same way. Sooner rather than later, hopefully.