It’s a cosmopolitan city with a thriving port and a diverse range of industries that, in some cases, stretch back more than 1,000 years.

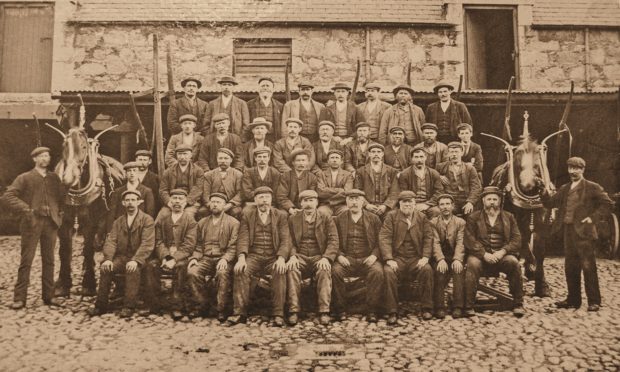

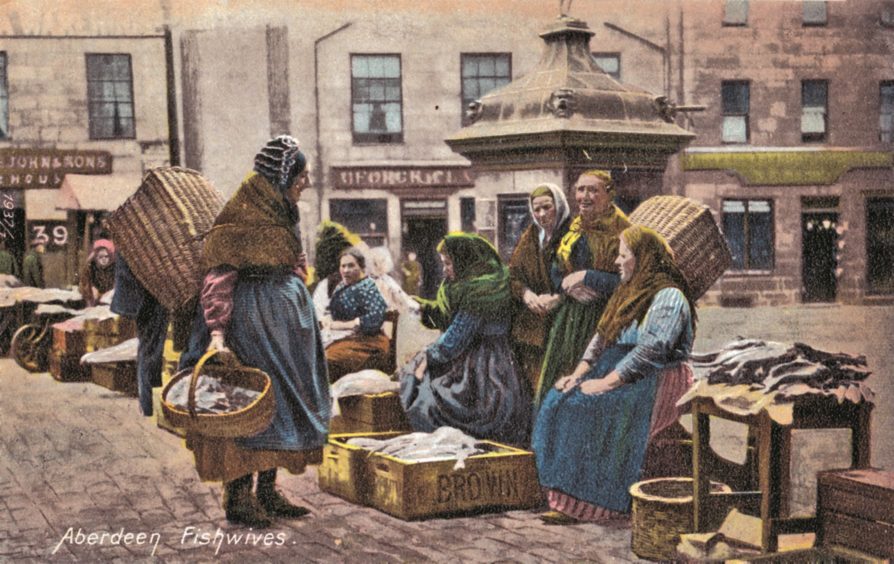

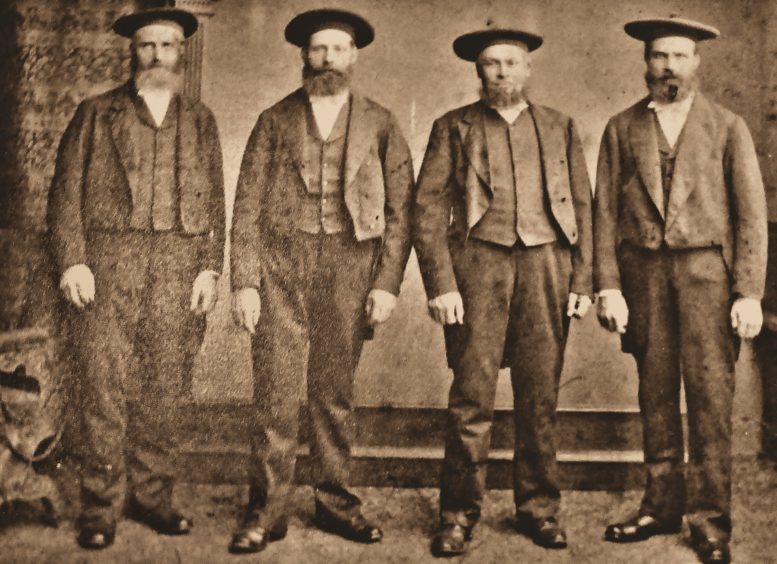

And, whether in the older trades of fishing, farming and fleshing or the more contemporary world of engineering and the energy sector, Aberdonians have never been afraid to roll up their sleeves and put their bodies through the wringer.

However, the Granite City’s myriad tradespeople haven’t always seen eye to eye as they have gone about their daily business.

On the contrary, as authors and historians Lorna Corall Dey and Michael Dey have revealed in their new book, Aberdeen at Work, disputes, protests and the fight for a fair wage have been a regular occurrence of life, particularly amid the Industrial Revolution.

Indeed, matters have occasionally reached the stage where police and other officials have quite literally been forced to read the Riot Act.

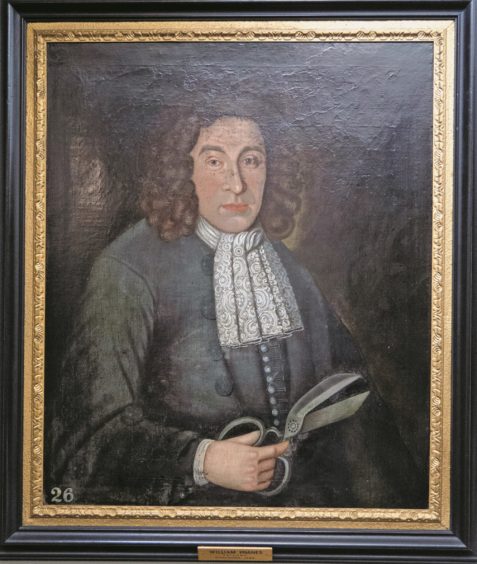

One might not imagine that tailors would have been at the forefront of equality and industrial action more than 200 years ago. But their crest includes the figure of Eve alongside Adam and women were able to work in various parts of the trade.

Yet, when the rest of Scotland’s male tailors combined to exclude them from the business, it was Aberdeen’s progressive brethren who ended this unfair practice during the 18th Century.

As a consequence, females were permitted to make clothing for their other women – but they could still not be members of the guild. Any advances tended to be in small steps.

Nonetheless, there was a schism between rival organisations in the city.

As the book recounts: “Aberdeen’s tailors and weavers were radical and coopers conservative. Towards the end of 1785, as America fought for independence from Britain, it was tailors and weavers who led the domestic struggle for greater openness and fairness in local government.

“Aberdeen’s streets filled with protesters demanding impartiality from the town council, whose burgesses were seen to favour some trades over others.

“Civil disagreements sometimes became physical. On one memorable occasion, a fight broke out at Shiprow between 50 pro-fairness wrights and a group of coopers.

“The melee continued up Marischal Street and into the Castlegate with the militia giving chase. Three wrights were arrested and locked in the Tolbooth, which, in turn, was stoned until the prisoners were released.

“Tensions in the town ran high with the Provost and his home both threatened, while councillors went into hiding.

“A trial followed, with defendants either being acquitted or given small fines.”

This was an entirely different time and place from anything that exists today. The authors have also unveiled the story of Thomas Edwards who worked long shifts at Grandholm Mills.

Nothing unusual in that, you might imagine – but this employee was just eight years old.

The book explains: “Notoriously long working hours that began with the early-morning shrill whistle to waken exhausted workers were addressed in 1833 when Factory Commissioners met with Aberdeen’s mill owners who insisted that shorter hours would damage their industry and only benefit foreign competitors.

“Some variation existed across the local manufacturers, but a normal week amounted to 72 hours, composed of six days for mill-hands, including children, who were ever under the scrutiny and the whip hand of an overseer.

“Most mills would only take children of 10 and over, but as Thomas Leys Hadden of Grandholm Mill explained, his plant would employ younger people ‘chiefly to oblige poor parents who live in the neighbourhood of the works and who otherwise cannot support them’.

“At just eight, Thomas Edwards was already working at Grandholm. This was in 1822 when children like him worked the same hours as adults: from 6am until 8pm.

“Living some two miles from his work, Thomas rose at 4am and returned home at 9pm.

“During his two years at Grandholm, Thomas was trained in heckling, carding and spinning and received anything from three to four shillings a week.

“But, as horrified as we might be by this working regime, Thomas ‘liked the factory’ and said that ‘it was a happy time for me’.

“Sam Howarth was only nine in 1812 when he began to work at the mill. As an old man, he spoke of his over 80 years’ service and the good feelings he had about his time there.

“He added: ‘The owners treated me well’ and were ‘very kind’ and gave him a pension.”

There were precious few people who lived until they were 70, let alone 90 at that stage. So these childhood working experiences were clearly not a millstone for everybody.

The meticulous approach of Lorna Corall Dey and Michael Dey evocatively spells out how Aberdeen has been shaped by its natural surroundings and location on the North Sea.

Long before the 1,000-plus years of the city’s recorded history, the area’s prehistoric people constructed megalithic stones and circles – many of which still exist in splendid isolation across the Mearns where Lewis Grassic Gibbon set his immortal Sunset Song.

Then, for centuries thereafter, granite from quarries across the area was deployed to build the city, as well as being exported around Britain and further afield to the United States, South Africa, Australia… wherever the hard-wearing stone was required.

As its population increased, a vast number of crafts and skills went into the development of Aberdeen – a community which sits between two rivers, both of them enabling trades such as fishing and papermaking and which have been bolstered by shipbuilding and textile mills.

Bakers and assistants hard at work at Aberdeen’s Strathdee Bakery in Granitehill Road, Northfield, in 1964.The city was a major fishing port and an important trading centre between Scotland and countries across the North Sea and, when oil was discovered in the Forties Field of the North Sea in October 1970, Aberdeen rapidly became the energy capital of Europe.

Today, the region’s natural landscape again dominates work and labour as companies move to invest in new energy sources harvesting wind and wave power.

Aberdeen at Work depicts a compelling story of the women, men and children who earned their living at countless occupations – some of which are common to every town and others unique to Aberdeen.

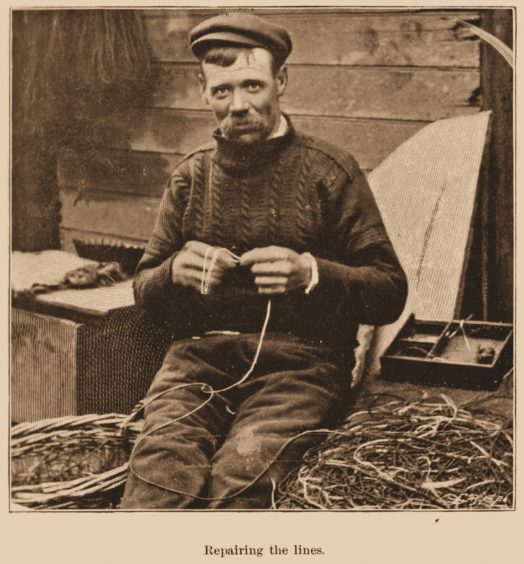

As one might expect, there is a strong emphasis on the ancient harbour, which played such a pivotal role for centuries and where the sight of fish quines and naval ratings, shore porters and harbour masters was a traditional part of the daily landscape.

And, while there has been a dramatic shift in work patterns, accompanied by technological advances and the transformation of society, the authors believe that the strictures of lockdown, impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, have demonstrated how many people carry out jobs which are integral to a city continuing to function in the worst of circumstances.

They told the Press and Journal: “If Covid-19 has taught us anything, it has shown how central work is to the more or less smooth running of society.

“The past six months has been a time of great psychological struggle during which many individuals and families have found themselves without work, forcing them to confront reduced standards of living and loss of a focus around which so many activities revolve.

“We had no idea when we embarked on Aberdeen at Work just how contemporary working lives would be dramatically transformed in a matter of months.

“The north-east has experienced equally profound changes over past centuries albeit more slowly, for example the rise and fall of the handloom weaver and Aberdeen’s trawling industry. This is what drew us to the subject of the book in the first place.

“Covid-19 has made us question the organisation of both work and labour such as home-working and the potential decline of the office. At the same time, an increase in online retail business has been accompanied by greater emphasis on local shopping.

“Regardless of the period – Neolithic, medieval, industrial – work matters.”

Short, sharp and to the point, this is one of the most resounding messages from a book that packs a very powerful punch.

- Aberdeen at Work is published this month by Amberley. All orders on the company’s website will receive 10% off the recommended retail price on all titles.

- For more information, see www.amberley-books.com

Info:

Lorna Corall Dey and Michael Dey have spent many years analysing the history of the north east of Scotland.

Lorna was born on the Black Isle in the Highlands, but has lived in and around Aberdeen most of her life.

A former lecturer in history at Aberdeen College, she went on to teach in schools, later in collaboration with Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums, while scripting and producing a DVD called Object Lesson, as an aid for teaching local history using museum artefacts and an interactive website.

Her first novel, Banana Pier, came out in 2011 with a second in the pipeline.

Michael Dey graduated in history and worked in the museum service in Aberdeen, specialising in social and industrial history.

He previously wrote The Granite City for Amberley.