A prisoner of war camp sprung up near Laurencekirk during the Second World War. Many Italian POWs housed there formed friendships with locals – ties that remained strong long after the war was over. Gayle Ritchie explores some of the stories behind this forgotten camp in the Mearns.

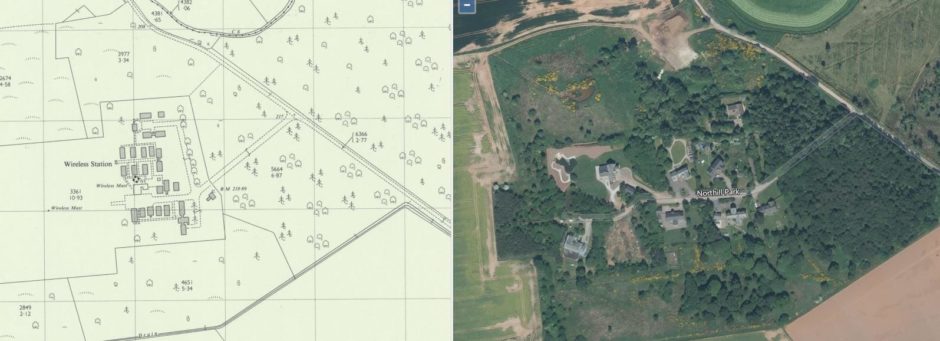

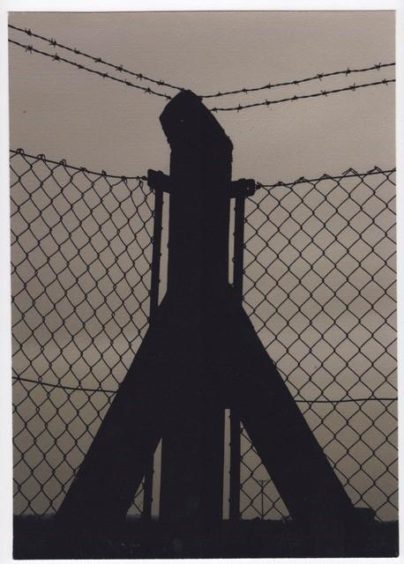

A few strands of barbed wire, some piles of rubble and a concrete track are all that remain of Northill POW camp.

But back in the 1940s, the camp near Laurencekirk housed hundreds of Italian and German prisoners.

The hailed from a variety of backgrounds – some were from shot down aircraft 0r rescued from sunken ships or submarines, while others had been captured in mainland Europe.

When the Second World War ended, the buildings began to rot and crumble and were then demolished to make way for a new housing scheme.

However, old memories die hard and so it is with Northill.

In many cases, friendships had been formed between POWs and locals which were sustained long after the war was over and the camp buildings forgotten.

Today, these treasured bonds remain in the collective memory of Mearns locals and their foreign friends.

Buddies

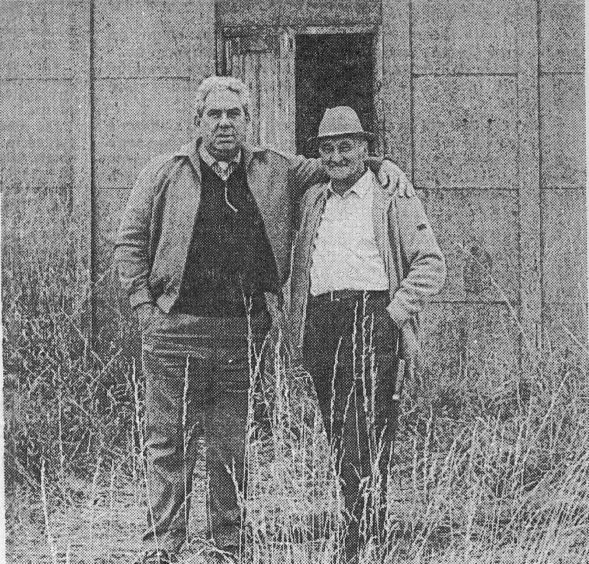

One such friendship was between the late photographer Reg Clark, then a young labourer from Laurencekirk, and Archangelo Gammaldi from Controne near Naples.

The two men became the best of pals.

Reg, a teenager at the time, worked for the company who built the camp.

The 15-year-old was something of a daredevil, climbing up the tallest tower in the camp to attach something to the top – a feat which won him the respect of his boss and a 2/6d bonus.

Archangelo, a builder to trade who worked on a farm at Auchenblae, was another admirer and he took it upon himself to befriend Reg.

The two lads got on like a house on fire, and when Archangelo confided in Reg that he had a girlfriend and wanted to meet up with her for a date, Reg agreed to break into the camp and stand in for him.

Archangelo crawled under the perimeter fence without difficulty and returned a few hours later, grinning from ear to ear.

This act of sneaking out became a regular thing – and it wasn’t just Archangelo who enjoyed the taste of freedom; many other prisoners escaped and headed into town to meet girls, while some preferred to take trips to neighbouring fields to trap rabbits.

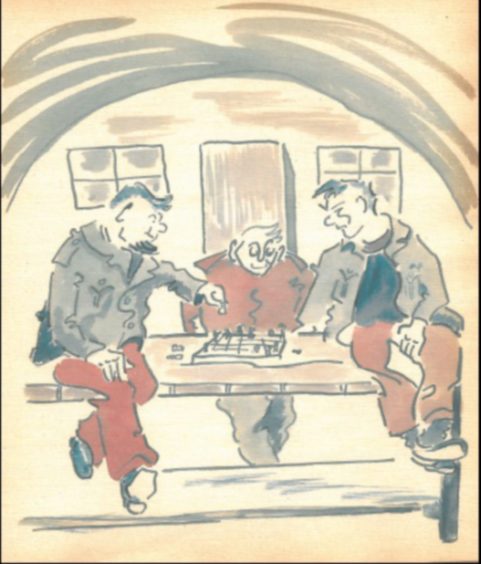

Reg broke into the camp numerous times – especially during the winter months – taking a prisoner’s place and playing dominoes.

He would put on the prisoner’s camp overcoat so that if a guard came in to do a head count, no suspicions would be raised.

A POW camp where prisoners could easily escape might sound absurd but the Italians at Northill were mostly considered low risk and therefore afforded a degree of freedom.

By treating POWs decently, locals felt their own relatives, imprisoned in Italy and Germany, might be treated equally well.

Friendship rekindled

After the war, Reg and Archangelo lost touch.

However, in the early ’60s, Reg’s wife met an Italian who was visiting Laurencekirk, looking to meet people he knew.

Reg’s son David, a photographer, said: “Mum rushed home to tell dad as she thought it would make a great story.

“When dad tracked the man down, it turned out to be Archangelo!”

The old pals were overjoyed to find each other and rekindled their friendship, sending Christmas cards and keeping in regular contact.

“In the mid-90s, mum and dad went out to visit him in Controne, Italy,” continued David, whose sister Maureen is still in touch one of his daughters.

“He lived in a village which had been hit by an earthquake. The home that he had built himself was untouched, so when people had to get their homes rebuilt, they went to the builder whose house was still standing!”

The couple visited again, and after Reg died 20 years ago, David’s mum visited a few more times.

“Many stories were told about Northill when they got together,” said David.

“Whenever a certain farmer’s name was mentioned, the locals would say, ‘grippy b*****d’ because they had always heard Archangelo say that when referring to the individual. It was quite hilarious.”

A second beer – 43 years on

A report in The Courier on September 11 1986 told how Reg, now a photographer with his own business in Laurencekirk, had another chance meeting with an Italian POW.

This was 43 years after Reg had gifted the prisoner a sneaky bottle of beer in 1943.

“The last time Reg Clark saw Antonio Campanione was as the Italian prisoner of war was marched into the guardhouse at Northill Camp, just outside the town,” read the report.

“That was 43 years ago when Reg, a slim 16-year-old, had incurred the wrath of a camp guard by taking the young Italian a bottle of beer.”

The pair, who had worked together at Northill building a new section to take German POWs, were brought together in 1986 in the very hotel in which Reg had bought the beer in 1943.

Antonio, a butcher and farmer, had decided to revisit his old camp in the Mearns and some of the farms where he had worked.

Arriving at Laurencekirk, he called in at the Boar’s Head to ask for directions along the country roads – and who should be sitting at the bar but Reg.

After exchanging quizzical glances, recognition suddenly dawned upon the two men.

Reg said at the time: “As a result of the beer incident, I had been posted to Fordoun aerodrome to help with laying the concrete runways while Antonio spent seven years in detention. That was the last I saw of him until he walked into the hotel.”

The camp had barely changed in the intervening years and as soon as he walked through the gates, Antonio recognised his old billet.

Sure enough, the painting he had done on the wall all those years ago, with chalk, paint scraped from old tins, lipstick and egg, was still there.

Even the fence under which he used to crawl in and out of camp either to trap rabbits or visit the town, was unchanged.

Antonio said at the time: “There are many ghosts here”.

From Reg, Antonio learned that he had travelled all the way to Scotland unaware that a fellow Northill POW with whom he had lost contact lived only 20 miles from his home near Salerno.

There are many ghosts here.”

Antonio Campanione

Antonio could only stay a few days but before leaving the Mearns, he shared a second beer with his “lost” Scots friend.

Warm welcome

Prisoners at Northill were welcomed into the community, with locals often making them meals and giving them produce from their gardens.

Often, as a way of saying thanks, prisoners would craft toys for local children.

Recently, a cigarette case made by an inmate at Northill was found in a house in Jedburgh.

The metal case shows an etched view from within the camp, the name of the camp – POW Camp No.75 – and boasts decoration on the reverse.

Some prisoners made slippers out of wooden date boxes and gifted pairs to local children.

One POW baked a birthday cake for a man with whom he’d become friends.

Jim Stuart’s grandfather had a joinery shop in Laurencekirk that employed Italian POWs.

“They were hard working and considered very skilled tradesmen,” said the 72-year-old retired surveyor.

“There was a high degree of trust in the prisoners. Some of the tools they used – chisels, knives and blades – could’ve easily been used as weapons.”

Jim’s granny secretly made the prisoners food as she took pity on them.

“That was frowned up because it was the days of rationing, so she didn’t tell many people about it,” he said.

“It was easy to get food for them from the farm – neeps, eggs, carrots – pretty basic stuff.

“It was nothing exotic but they really appreciated her bowls of soup. I don’t think otherwise they got much.”

There was a high degree of trust in the prisoners. Some of the tools they used – chisels, knives and blades – could’ve easily been used as weapons.”

Jim Stuart

When Northill was turned into a housing scheme, Jim understood it was the end of an era.

He said: “I never got the impression people were emotional about it. It was felt that it was simply a Second World War necessity.”

Ye’ll ken Laurencekirk, then?

Mike Robson, chairman of the Howe o’Mearns Heritage Group, remembers exploring Northill POW camp in the 1950s.

By this time, it was more or less derelict – “a home for doos” – having been part of a radio station linked to Friockheim.

“A pal and I crawled under a wire and started shooting doos (rock doves), which like to live in abandoned buildings,” said Mike, a retired vet.

“I always found the history of the camp fascinating – how it had first housed Italian PoWs until Italy surrendered in 1943, and then German POWs.

“It housed POWs during the repatriation period until 1947 and after the war, it became a borstal. I remember you’d see many of the boys out picking tatties.”

Mike crept around in the buildings, which included dormitories and a military section.

“The dormitories had long corridors and the beds had no mattresses,” he said.

“There were little stoves to heat the buildings, which must have been cold.”

Years after the POWs had returned home, stories would pop up of former prisoners bumping into Mearns locals abroad.

“A couple from St Cyrus were on holiday in Italy and the lady was Scots-Italian,” said Mike.

“Three old guys sitting on a bench saw the couple as they explored an old chapel and asked, ‘where about do you come from?’

“The lady told them St Cyrus, a place in Scotland, and said they’d not know it.

“A voice piped up and said, ‘Ye’ll ken Laurencekirk, then?’. It turned out to be a former prisoner!”

Many POWs had worked in Stracathro Hospital and formed relationships with nurses which led to all kinds of discoveries years and sometimes decades later, with locals finding out they had long-lost Italian fathers!

When the Germans arrived at Northill, prisoners were divided into Nazis and non-Nazis, said Mike.

“The non-Nazis were allowed out to work on farms and strong bonds were formed with farmers and locals.

“Some Germans came back to visit families who’d looked after them and one former POW left money in his will for what he called his ‘foster family’ after he died.”

Who were the POWs?

Thousands of POW camps popped up across Scotland, UK and overseas during the Second World War – but most have been destroyed.

The POWs came from a variety of backgrounds. They were brought to Britain or shipped off to Canada or later, the USA, which was to safeguard security as much as it was due to lack of space.

Alan Stewart, the author of North East Scotland at War – Events and Facts 1939-1945, has delved deep into the history of POW camps in Scotland.

“Prisoners would often progress through a series of camps, where their political allegiances were determined,” said Alan, of Ellon, Aberdeenshire.

“Non-Nazis were graded ‘white’, questionable cases were ‘grey’, and hardened Nazis (such as Waffen-SS or U-Boat Crews) were ‘black’.

“As a general rule, the ‘blacker’ the grading, the further north the camps where prisoners would be housed were.

“The most ardent Nazis were normally sent to the Scottish Highlands.

“Racecourses, football grounds and parks were favourite locations for camps. In a number of cases these would have been tented accommodation rather that huts.”

From July 1941 onwards, Italian prisoners captured in the Middle East were brought to Britain.

This was the first major influx of prisoners of war to the country.

“These Italian POWs presented one way of alleviating manpower shortages, particularly in agriculture,” explained Alan.

Following the Italian surrender in 1943, 100,000 Italians volunteered to work as “co-operators”.

To house these co-operators, smaller-scale PoW camps were built which were called POW hostels.

“These hostels were still prison camps with a non-commissioned officer in charge to oversee the day-to-day running and organisation,” said Alan.

“Residents of the hostel were deemed a lesser risk than many Germans and were given considerable freedom to mix with local people.

“Most Italian POWs worked on local farms, providing manpower to provide for the increased need for food and produce because of the war, or they worked on bomb sites clearing up rubble.”

Tragedies

During Alan’s research, he discovered a number of Northhill prisoners were involved in tragic accidents.

In one incident, farmer George Lindsay, his father John, and Italian POWs Enzo Tanzi and Filippo Balduinotti were working in a field near Nether Wydings Farm at Fetteresso.

“The group were picking potatoes using two horses to pull a potato digger on November 11 1944 when a low-flying aircraft crashed into the field killing Lindsay and Tanzi and two horses while two other people were badly injured,” said Alan.

“Then on May 9 1946, a German POW, Otto Schmidt, was killed after being hit by a train near Laurencekirk while returning from his job at a nearby sawmill.”

Alan has another book due for release in January 21 – North East Scotland at War – Events and Facts 1939-1945 Book 2.

His first book can be purchased at cabroaviation.co.uk

Art project

St Cyrus-based artist and printmaker Sheila MacFarlane worked on a project about Northhill POW camp in 2008.

She exhibited her work, consisting of photos and text, at galleries around the north-east.

“I began to look at the history of the Italians in the local area and discovered Northill,” said Sheila.

“I located the site, now a modern housing development. The road into it was virtually unchanged although there was little of the old to be seen on the site.

“There was some barbed wire and what I think was the remains of the old sewage system.”

Sheila visited Laurencekirk Library and talked to locals about the site, including Reg Clark, poet Raymond Vettese and musician Sandy Mathers.

Her aim was to create something “simple and a bit alternative”.

“I played around with words and images in a very primitive sort of way. Northill certainly tells a fascinating story.”

For more details on Sheila’s work see sheilamacfarlane.net

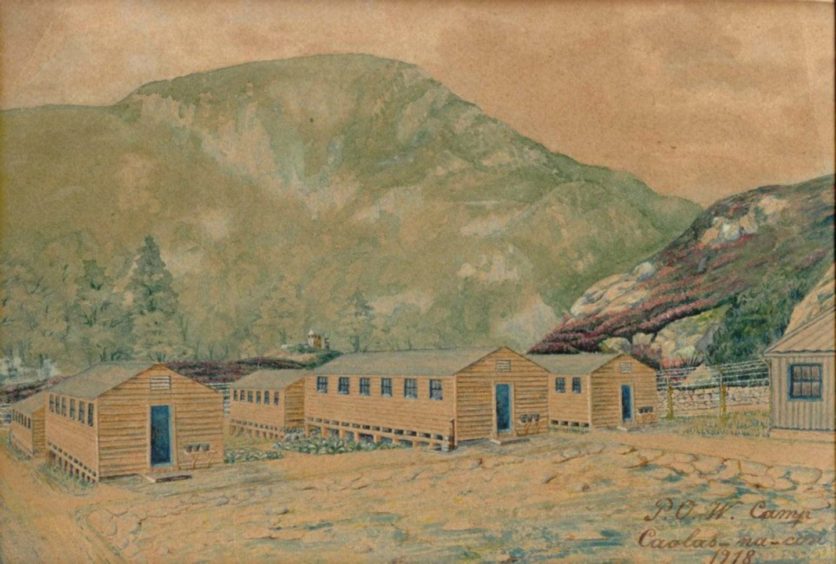

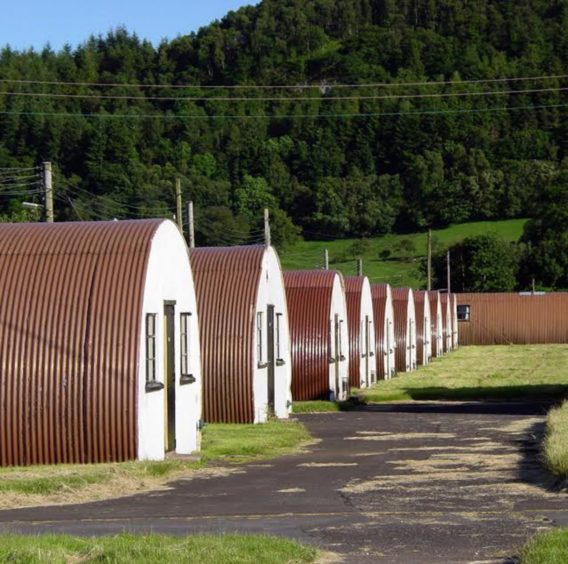

Cultybraggan

While most POW camps were destroyed, Cultybraggan Camp – also known as Camp 21 Comrie – is the only preserved camp in Scotland.

Nestled beneath the rugged Highland Perthshire hills, it held some of the most hard-line Nazis captured during the Second World War.

Today visitors can explore Cultybraggan Camp, with 84 original Nissen huts surviving in a green space near Comrie.

At its height, the site was home to 4,000 Germans POWs, before becoming an MoD training camp from 1948 to 2004.

It was bought by Comrie Development Trust (CDT) in 2007, amid fears it would be demolished.

Now, it hosts a visitor centre, heritage trail and community orchard with some huts hired to an eclectic mix of local businesses such as a pottery and bakery.

Since August 2019 (closed as a result of Covid and reopening in Spring 2021), visitors have been able to enjoy a storyboard heritage trail and installations including a refurbished jail block and a recreation of prisoner accommodation in one of the 100ft-long huts.

Adorning the walls of one cell are a selection of cartoons drawn by a German POW named Peter.

Some show German prisoners carrying out manual labour against a backdrop of intimidation, violence and even murder.

Others show them happily playing cards, enjoying snowball fights, reading racy magazines and watching theatre and musical performances.

Also on display is Bunte Buhne, a book of sketches and programmes of theatre shows performed by Nazi prisoners.

Some depict a fondness for the Scots… and scantily-clad women.

As prisoners left camp, many didn’t forget the kindness of locals.

One former inmate, Heinrich Steinmeyer, bequeathed his home and life savings of £384,000 to CDT.