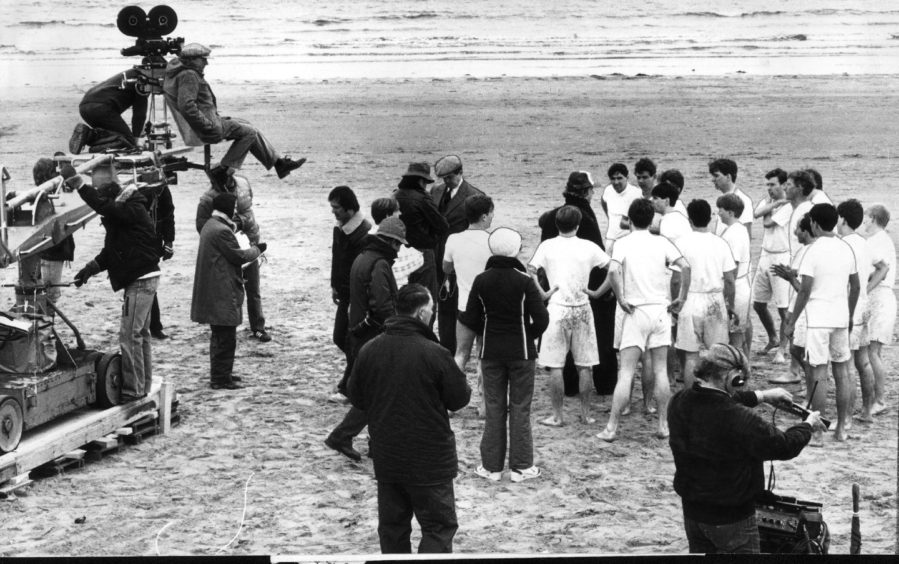

A twist of fate on the West Sands in St Andrews changed the face of movie history and provided the striking opening to Chariots of Fire.

The famous slow-motion beach run depicting white-clad runners training barefoot on wet sand as waves break close by was actually a reshoot.

The original scene was shot on April 24 1980 but sand got in the camera and scratched the negative right the way through.

Film crews would return to St Andrews to shoot the sequence again a week later.

The rest is history.

Water was rougher on second shoot

Dr Tom Rice, a senior lecturer in film studies at St Andrews University, said what seemed to be a disaster at the time turned out to be really good news.

“David Puttnam, the producer, saw this as more good fortune, as the water was rougher on their return and this was much more visually striking,” said Dr Rice.

“The film benefitted from the reshoot and indeed from the late addition of a new piece of Vangelis music.

“In isolation it presents universal, and perhaps aspirational, values – the idea of teamwork and camaraderie, freedom, innocence – while also projecting a particular image of British heritage which would be very marketable on film in the 80s and 90s.

“It is worth pointing out however that this was never intended to frame the film.

“The original scripts had a different beginning and ending but fairly late in the day during editing, the producers instead decided to use this sequence as the film’s opening.

“Similarly Hugh Hudson originally wanted to use a different piece of Vangelis’ music for the sequence.

“It was interesting also to read the earlier drafts of the script that had an entirely different opening scene which was one set in contemporary London where through a TV in a shop window, we see an East German athlete given his gold medal.

“They did, I think, shoot that scene but then decided the beach footage worked better.”

Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams

Chariots Of Fire told the story of Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams, who both won gold medals for Britain at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

It highlighted the Christian stance of Eric Liddell never to run on a Sunday and the anti-Semitism Abrahams had to endure during his life.

It was the storyline that inspired Vangelis to compose the soundtrack to “those few young men, with hope in our hearts, and wings on our heels”.

“Filming was taking place in Crieff and Edinburgh and so they needed a suitable site in Scotland for the beach sequence,” said Dr Rice.

“It would be too expensive to relocate the shoot down to Broadstairs – the historical location – and so St Andrews was chosen, largely for economic reasons and for convenience.

“This was ultimately remarkably good fortune for both the producers and the town.

“The beach sequence showcases a particular vision of the town – the golf course, the beach, the gothic architecture – which has served to promote St Andrews internationally.”

Today, governments, local councils, and tourist boards recognise the enormous cultural and economic value of bringing a film shoot to their area.

Filming was not universally welcomed

However, back in 1980 the filming in St Andrews was met with, at best, indifference.

One regional councillor complained about the fact that Links Place was closed for traffic for what they saw as a ‘frivolous reason’ and, equally dismissively, ‘objected very strongly to time being wasted helping film people’.

Dr Rice said: “The level of disruption on a Thursday morning in April does not seem too extreme, but this still prompted one local to complain that traffic was held up for up to 10 minutes!

“It’s notable that even those that were enthusiastic about the shoot saw very short-term benefits – additional income for shops, hotels and businesses for a couple of days – and some councillors did acknowledge that the town might benefit from some additional publicity around the film’s release, but no-one imagined the wider, long-term benefits of presenting St Andrews to the world.

“It is of course also worth remembering that no one knew, or expected, much from this film and that film tourism was not yet an established phenomenon outside Hollywood.

“There was certainly no expectation that this would be a widely seen Oscar winner.

“Indeed, many of the extras were reportedly recruited in the local bars the night before.

“The more athletic ones, ideally you would imagine with less of a hangover, were brought together by the late Donald MacGregor, local Olympian and Madras school teacher.

“MacGregor recruited local athletes from the University and Fife Athletic Club, but didn’t take part himself as he didn’t think it was worth taking a day off work.”

1920s cars were brought to St Andrews

The auditions were held at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club in St Andrews and in Leven.

Hamilton Hall, a fine red stone student resident hall, overlooking the last green on the Old Course, was transformed into the Carlton Hotel.

The Carlton was used for outside scenes but Russack’s Hotel was used for interior scenes.

Cars from the 1920s were brought in by the film makers to give background authenticity to the famous running scene on West Sands.

Dr Rice said: “This is perhaps the single most recognised and widely circulated image of the town.

“There are a couple of interesting points here.

“Firstly, this is not identified as St Andrews in the film but is instead supposed to be Broadstairs, 600 miles south.

“Yet in the popular imagination, this film – and the history it represents – is now associated with St Andrews rather than Broadstairs.

“We see this in all sorts of ways. For example the Olympic torch relay in 2012 was taken onto West Sands (but not onto the beach in Broadstairs) as through this film, St Andrews becomes linked to, and part of, this Olympic history.

“Secondly, the film’s longevity can be attributed in part to this sequence.

“It is this sequence that is constantly reworked – from an episode of Sesame Street to adverts for all manner of products, ranging from Nike to prostate examinations in South America – and it is this sequence that was used at the Olympic Opening ceremony to represent British cinema in 2012.

“I suspect today that many people know the sequence – the running on the beach and Vangelis score – but have not seen the film.”

Integral part of British heritage cinema

Dr Rice said the film has been memorialised, and exploited, in all sorts of ways, from beach runs and charity events, to hotel bars and a plaque by the beach.

“What we see now is a sequence that is used locally, nationally and globally – whether for tourism in St Andrews, as part of Scottish history (particularly through the story of Eric Liddell) but also as an integral part of British heritage cinema,” he said.

“We’ve also seen many other films come to St Andrews over the past 40 years.

“These include a Bollywood production in the late 90s, Never Let me Go (2010) and Tommy’s Honour (2016), as towns increasingly recognise the huge value of bringing productions to a local community, particularly in projecting St Andrews to an international audience.”

Olympic legend Eric Liddell’s journey of faith

The movie tells how Liddell was boarding a boat to the 1924 Paris Olympics when he discovered that the qualifying heats for his event, the 100-metre sprint, were scheduled for a Sunday.

A devout Christian, he refused to run on the Sabbath and was at the last minute switched to the 400 metres.

In truth, Liddell had known the schedule for months and had decided not to compete in the 100 metres, the 4×100-metre relay, or the 4×400-metre relay because they all required running on a Sunday.

The press called his decision unpatriotic, but Liddell devoted his training to the 200 metres and the 400 metres, races that would not require him to break the Sabbath.

He won a bronze medal in the 200 and won the 400 in a world-record time.

In the 200m he finished in front of Abrahams who had won gold in the 100m Liddell missed.

After quitting athletics, Liddell soon returned to China, where he had been born, to continue his family’s missionary work.

He died there in 1945 in a Japanese internment camp.

Under a prisoner-exchange deal he could have left the camp, but gave this up so a pregnant woman could go in his place.