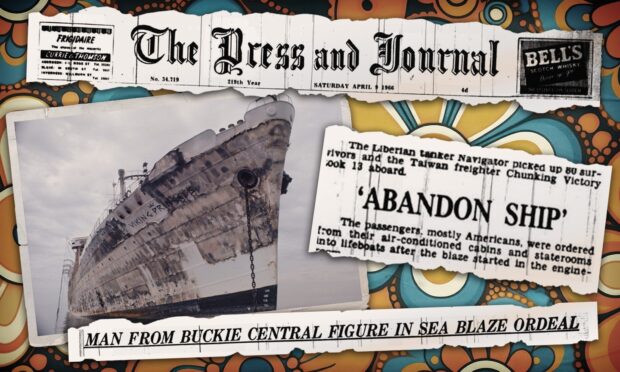

The story of Robinson Crusoe, wrecked on a remote tropical island, is as alive in our imaginations now as it was 300 years ago when Daniel Defoe’s novel first appeared.

There’s something about desert islands – we fantasise about rolling white beaches, palm trees dropping coconuts, gently lapping waves, maybe a footprint in the sand.

Paradise?

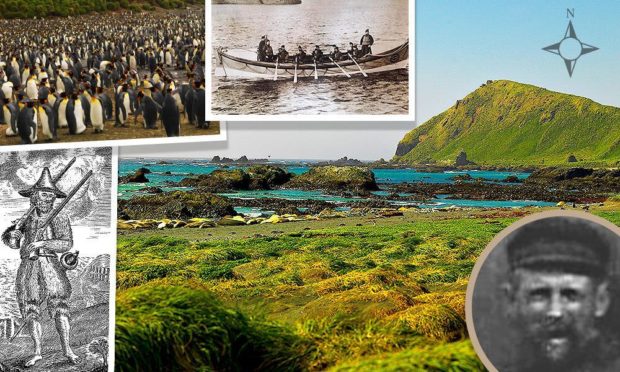

Well, not quite. Not for a young Caithness seafarer who found himself marooned for four months on an inhospitable rocky lump of an island 1,000 miles off Tasmania more than 140 years ago.

Wick’s own Robinson Crusoe was Alexander MacKay, remembered in his obituary as ‘always ready to answer the call of duty’.

Wick’s Robinson Crusoe

Born in 1855 to James MacKay and Rachel Brotchie, Alexander took to sea as a boy and sailed around the world meeting with adventures ‘as thrilling as ever recorded in sea stories’.

Undoubtedly one of the biggest occurred in July 1877, when he was a member of a 19-strong crew on a seal fishing expedition aboard the 66 ton schooner, SV Bencleugh, owned by Blairgowrie man, John Sen Inches Thomson.

They had left Port Chalmers New Zealand, where the ship was built, looking for Emerald Island, a phantom island first reported in 1821.

Finding no trace of the island, they turned back towards MacQuarie Island where they intended to slaughter seals for their oil.

But for the next three weeks they struggled against storms, snow, fog and hail, unable to land.

During a break in the gales, they managed to land a supply boat, but the next day, a huge wave topped the Bencleugh and forced it into a cleft in the reef.

With its row boats long since washed overboard, the only way for the crew to land was for a volunteer to swim ashore with a rope.

Alexander’s obituary relates that with the ship in danger of breaking up, he volunteered to be the one to swim ashore.

After a desperate struggle with the elements, he made it and helped pull the rest of the crew to safety.

However John Inches Thomson was aboard the ship at the time and in his own 1912 account of the shipwreck, Voyages and Wanderings in Far-Off Seas and Lands, he recorded that it was he, as the ship’s owner, who swam ashore with the rope, and succeeded on his second attempt.

All the men made it to shore, with four sustaining injuries.

‘Nothing could warrant any civilised creature living on such a spot’

MacQuarie Island is now a World Heritage site, with UNESCO describing it as ‘the exposed crest of the undersea MacQuarie Ridge, raised to its present position where the Indo-Australian tectonic plate meets the Pacific plate.

‘It is a site of major geo-conservation significance, being the only place on earth were rocks from the earth’s mantle, nearly four miles below the ocean floor are being actively exposed above sea-level.”

Half a century earlier, explorer Captain Douglass of the ship Mariner called MacQuarie Island “the most wretched place of involuntary and slavish exilium that can possibly be conceived; nothing could warrant any civilised creature living on such a spot”.

The Australian authorities would later consider using the island as a penal colony, but ruled it out as too harsh even for that.

A diet of penguin eggs

The marooned seal hunters gratefully took refuge in huts in place from earlier expeditions.

Many had ditched their coats and boots for the swim ashore.

Next day, they managed to salvage what they could from the Bencleugh before it broke up.

Its sails became clothing, blankets and covers for the huts.

Daily beach-combing rewarded the men with several boxes of food, a whole box of tobacco and a rifle.

None the less, food was scarce, and the men lived mainly on penguin eggs.

One man was lost, chief harpooner Harry Whalley, who died in one of the huts from his injuries, and was buried on the island.

A fortnight later, the Bencleugh’s sister vessel Friendship, which had left Port Chalmers shortly after Bencleugh, arrived and picked up the injured men and as many other crew members as possible before returning to Port Chalmers.

Alexander wasn’t included in that run, and he remained on the island, keeping busy sealing hunting with the rest.

It took an extremely challenging four months for Friendship to return, by which time the crew had made 15 tons of seal oil.

In time for Christmas, the rescued sailors were taken to Dunedin where they met with a rapturous welcome – and for Alexander, a poignant connection with home.

According to his obituary: “Mr MacKay’s services were recognised by the people and the owner of the ill-fated ship whose son had been on board.

“He was presented with a gold watch and ring in appreciation of his gallantry.

“One interesting coincidence occurred when Mr MacKay was in Dunedin.

“He entered a tobacconist shop and the first thing that caught his eye was a copy of the John O Groat Journal.

“The shop keeper he discovered was also a native of Wick.”

Alexander continued his swashbuckling youth on the high seas.

“He sailed in the old tea clippers the fame and glory of which will never die and took part in the races from Chinese waters,” records his obituary.

Family legend has it that he sailed on the Cutty Sark.

Encounter with Shackleton

Years later, Alexander was to meet the Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, who was in Wick on a visit.

He related that Shackleton had visited MacQuarie Island and they had a long conversation, during which Shackleton produced photographs of the island in which the hull of the old ship could still be seen.

He also had a photograph of the grave where their fallen comrade had been buried.

‘Hardships did not change his nature or break his unconquerable courage’

The traumas of being a castaway didn’t put Alexander off pursuing his maritime career, and his courage and selflessness became the stuff of local legend.

His obituary writer puts it this way:

“His genial and unselfish disposition and honest integrity of character earned for him the respect of all who made his acquaintance either on sea or land.

“Under summer’s suns or in winter’s storms, by daytime or in night he was always ready to answer the call of duty.

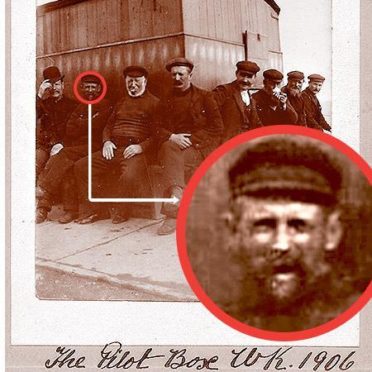

“Difficult and dangerous tasks often fell to his lot especially in the days when sailing ships predominated in numbers, but he never failed and was in truth a Master Pilot.

“Since the introduction of motor power the work of the pilots has not been so spectacular or so strenuous, but for many years before that Mr MacKay saw perilous and adventurous service.

“His work as coxswain of the local lifeboat will long be remembered for he was instrumental in saving many lives from wrecks in Wick Bay when the sea was at its wildest during south easterly gales.

“Hardships did not change his nature or break his unconquerable courage.”

Courage and skill put to the test

Alexander had only been eight days coxswain of the harbour lifeboat when his courage and skill were put to the test.

“On November 26 1885 the ‘Norge’ a large Norwegian barque was driven into Wick Bay by a severe storm.

“Mr MacKay, the then newly appointed coxswain organised a volunteer crew and in the face of the greatest danger rowed to the wreck which lay on the bed of the river.

“One man was lost in the raging seas before the lifeboat arrived – he fell from the rigging of the storm swept ship in full view of many onlookers on the land – but the other ten of the crew were saved by the gallant lifeboat men.

“Many other lives were saved in the bay by the crew of the harbour boat with Mr MacKay in charge before he took over the same position with the Lifeboat Institution. He did valuable work for that Institution before his retiral in 1911 after 30 years as coxswain superintendent.

“His genial and unselfish disposition and honest integrity of character earned for him the respect of all who made his acquaintance either on sea or land.

“For almost 46 years he was regularly on duty as a pilot in Wick and during that long period he made the acquaintance of the officers and crews of almost all trading vessels which called at the port.”

As master pilot at Wick, Alexander would normally have retired at 65, but such were skill and vitality that he went on for a further 11 years.

A year after retirement Alexander, then of Smith Terrace in Wick, was getting ready to leave home for a day out when though apparently in good health, he suddenly collapsed and died from heart failure.

“Mr MacKay’s death will be deeply regretted not only by the whole community of Wick, his native town, but by a whole host of seafaring friends in all quarters of the globe,” his obituary reads.

“Mr MacKay’s quiet, cheerful, good fellowship continued to the end and his death has meant the loss to Wick of a worthy yet unassuming son.

“The flag flying at half mast at the Pilot House this week has been the symbol of the community’s sorrow.

““Few men have been held in greater esteem than Mr MacKay.”

Masonic rites

The funeral in Wick was conducted with Masonic rites, Alexander being a keen freemason.

“Rev. A Robson, M.A. and Rev N C Robertson, Central Church – to which Mr MacKay belonged and in which he took a great interest – officiated at the house and Rev A Ross conducted the Masonic Service.

“There was a very large parade of the Masonic Brethren at the funeral and a great concourse of other townsmen.

“Harbour pilots acted as pall bearers.

“Among many floral tributes were wreaths from Wick Pilots, the North of Scotland Steam Navigation Co., Messrs Duncan & Jamieson Ltd., Messrs William Leslie and Co. and St Fergus Lodge of Freemasons.”

Alexander left a widow, Helen, three sons, James in Vancouver, Donald and Harry in Chicago and three daughters, Mrs Miller in Fraserburgh; Mrs Cormack in Chicago and Miss Ivy MacKay staying at home in Wick.

We are indebted to the Wick Heritage Society for telling us about Wick’s own Robinson Crusoe and Alexander’s great-granddaughter Jane Amy McKay.