Scotland’s footballers have never taken the easy path to glory when they have the option of marching down the Via Dolorosa.

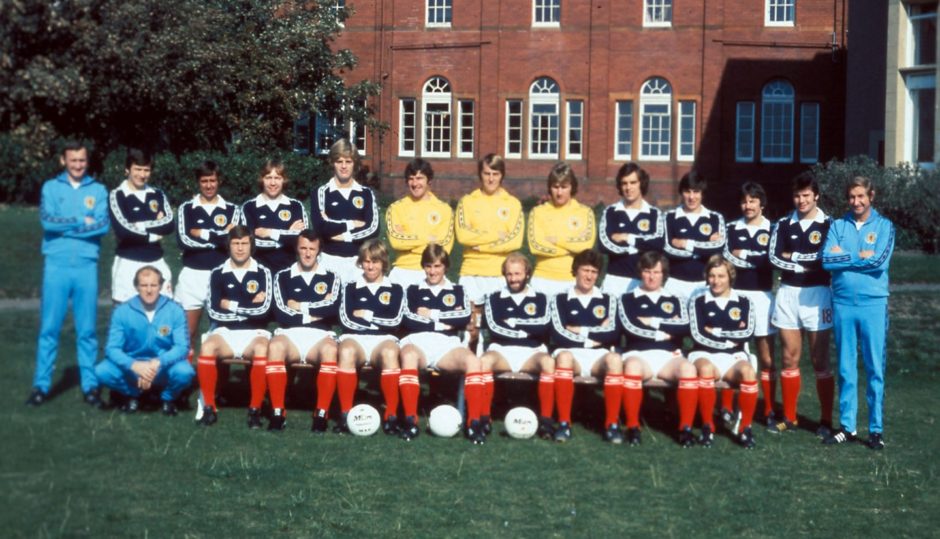

Ever since the World Cup in 1974, where Willie Ormond’s men didn’t lose a match, yet crashed out in the group stages in Germany, their involvement at major tournaments has been blighted by premature elimination.

There was the hapless campaign in Argentina in 1978 where Archie Gemmill’s heroics and a wonder goal which later inspired a ballet couldn’t act as the catalyst for the three-goal victory they needed against Holland.

And the crushing disappointment of the 3-0 defeat at the 1998 World Cup where the Tartan Army had worked out the maths required to progress, but hadn’t calculated on their team failing to show up against Morocco.

Will it be the same old story?

Even at the current European Championships, where there is ample room for misfiring teams to advance by winning just one game, Steve Clarke’s side are staring at the exit door unless they can overcome Croatia: the country which just happened to reach the World Cup final in 2018 and whose players have punched above their weight on the global stage for several years.

Yes, the Scots were tenacious and worked their socks off in drawing against England at Wembley, but a sense of proportion is badly required: after two games, they are bottom of the group, haven’t scored a goal in the tournament and have to beat the Croats to have any chance of qualifying.

Some people still have a tendency to prattle on about Scotland having a small population, as if that is any excuse for decades of underachievement.

But they are usually less keen to dwell on the fact that the likes of Croatia, a country with just 4.3 million people, has surged up the international rankings, whereas the Scots, which has 5.5 million, have struggled to keep pace, despite the nation’s fervent obsession with the game.

Success can’t be taken for granted

For many small countries, sporting success is at best sporadic and cyclical. But there are definite signs that the globe is shrinking in the beautiful game. We saw that with Iceland at the 2016 European Championship and Belgium and Croatia – who have a combined population of fewer than 15 million folk – were involved in a semi-final at the most recent World Cup.

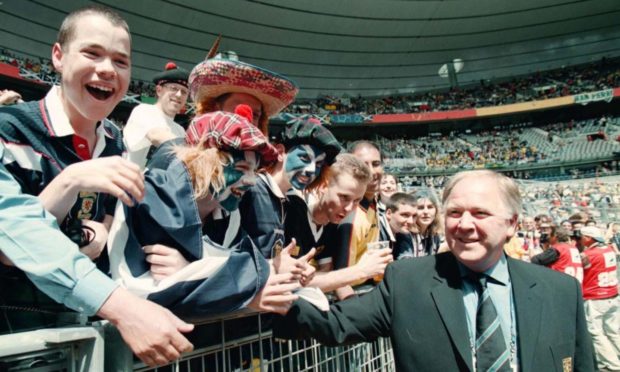

Former Scotland coach Craig Brown speaks with more authority on this subject than almost anybody else in his homeland. As the beetle-browed individual who guided Scotland to five major competitions – including three World Cups – he has closely examined the fashion in which other parts of Europe have adapted to the demands of modern football.

And he recognises the days have long gone when the SFA could cherry pick from thousands of youngsters who were prepared to play on old-fashioned ash and blaes pitches in howling gales and the worst of winter’s weather.

Brown has visited emerging countries

Hence his knowledge of why teams such as Croatia, fuelled by talents in the mould of Luka Modric, made such stunning progress in the same period that the Scots were meandering down a cul de sac of vulnerability.

He said: “When the old Soviet Union broke up, you had 15 countries emerge from that, as well as Russia, and all of them are very proud of their identity, so they pour money into sport and they all take it really seriously.

“I look at a country like Croatia which has made progress at every age-group level and, of course, that’s to be applauded. Sometimes, nations produce just one special group of players and that is it. But what has happened in Croatia is no accident at all if you have followed their development.

“It isn’t just them. A lot of people went on about Iceland doing well at the 2016 European Championships [where they reached the semi-finals and beat England 2-1]. But do you know they have seven full-sized indoor pitches with state of the art amenities. That is with a population of just 350,000.

“I also remember, when I was in charge of the national side [in the 1990s], making a visit to Norway and finding out on my travels that every village had a government-backed indoor sports arena.

“Alright, their climate is more severe than ours, so they need more indoor facilities which can be used 12 months of the year.

“But I think it helped to explain why so many of their youngsters were actively involved in sport, whether it was football, hockey, basketball, cycling or whatever.”

Lessons are gradually being learned

There are people in Scotland who appreciate that the dearth of modern amenities provides a major reason for the dwindling participation numbers in many pursuits and team sports in particular.

In the absence of 21st century-class venues, it isn’t surprising that so many kids prefer their XBox to a penalty box and would rather improve their scoring on their portable devices than go to a football centre.

However, some positive advances have been made in recent years. The creation of the Aberdeen Sports Village and the development of the Aquatics Centre point to what could be achieved with enhanced levels of investment.

But, as one former Scotland Commonwealth Games competitor told me recently: “We talk about wanting to help youngsters and give them the chance to chase their dreams. We even finance a lot of the elite performers.

“However, far too often, the athletes who do end up succeeding on the international stage manage it in spite of, not because of, the system.

“Look at Andy Murray. He left Britain and went to Spain to be the best he could be in tennis and he has won Grand Slams and Olympic titles. He is one of the most recognisable Scots on the planet.

“But now, his mum [Judy] wants to build a tennis centre in Scotland and yet she has hit a massive brick wall every step of the way. It’s crazy. We just don’t seem to learn from what other countries are doing.”

Lottery money isn’t enough on its own

This is a wearily familiar refrain to those of us who have charted Scotland’s highs and lows when they participate in elite events such as the World Cup, the Olympics and the Commonwealth Games.

I once heard former world champion runner, Liz McColgan – who surged to golden glory in Tokyo 30 years ago – discussing the issue and arguing for genuine sustained investment in sport as long ago as the mid-1990s.

She added that it wasn’t enough to rely on Lottery funding: in her view, international success could not be achieved with cash alone. There had to be a coherent route map to encourage youngsters firstly to enjoy themselves at the grassroots as the prelude to assisting the most talented in their ranks.

As the showdown with Croatia beckons this week, precious little has changed in Scotland even if the Tartan Army have enjoyed their trip to London in numbers not witnessed since the 1990s.

Yet the fact remains that other parts of the world are moving on and focusing on responding properly to the challenge of inspiring future generations – and they were doing this even before the Covid pandemic struck.

Ultimately, as Craig Brown said: “You can no longer rely on kids wanting to turn up in the pouring rain for football practice.

“They have other things to do and they have other places to go.”