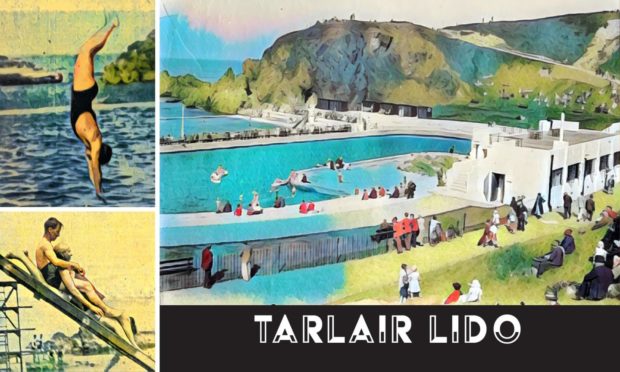

When the aspirational Art Deco Tarlair outdoor swimming pool opened in 1932, it was said Macduff would become the “Mecca of the Moray Firth”.

It brought a slice of the Art Deco glamour of resorts on the French Riviera to the heart of historic Banffshire.

Outdoor swimming pools – later known as lidos – were a staple of British seaside resorts in the days before package holidays.

Sun-seekers and swimmers flocked to coastal communities during the 1930s: it was the golden age of the open air pool.

Built as recreational facilities by local councils, 169 sprung up in the UK alone during that decade.

Bold vision

Ahead of his time, Macduff councillor John Hird was a visionary man.

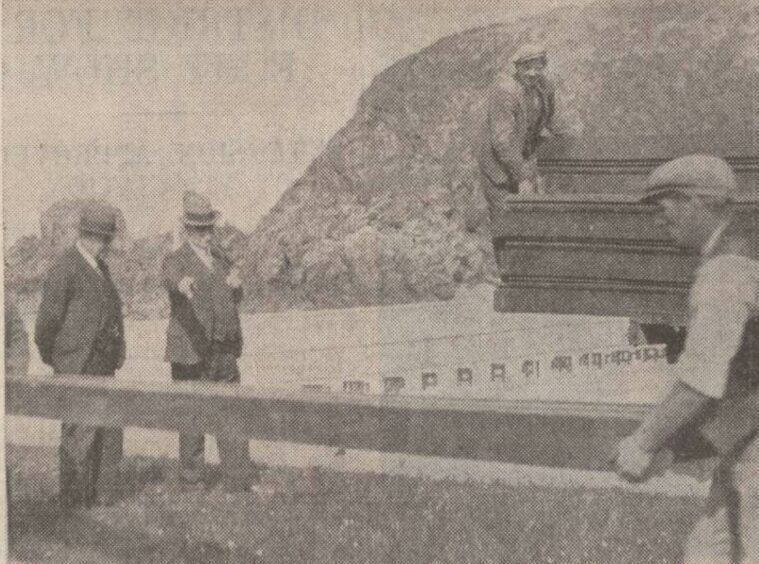

Upon seeing the success of similar schemes in southern Scotland, in 1929 he made the case to Macduff Burgh Council for a pool at the nearby Salmon Howe where he was fond of taking a dip.

He saw an opportunity to turn Macduff, a small herring port, into a tourist resort, but his colleagues were not interested.

Mr Hird, since dubbed “the father of Tarlair pool”, was persistent.

He held a fundraising swimming contest at Macduff Harbour, and presented the £80 proceeds to his fellow councillors to start a swimming pool fund.

With the backing of enthusiastic locals, fundraising began for the scheme – which was no mean feat at an estimated cost of £4,000 – £278,650 in today’s money.

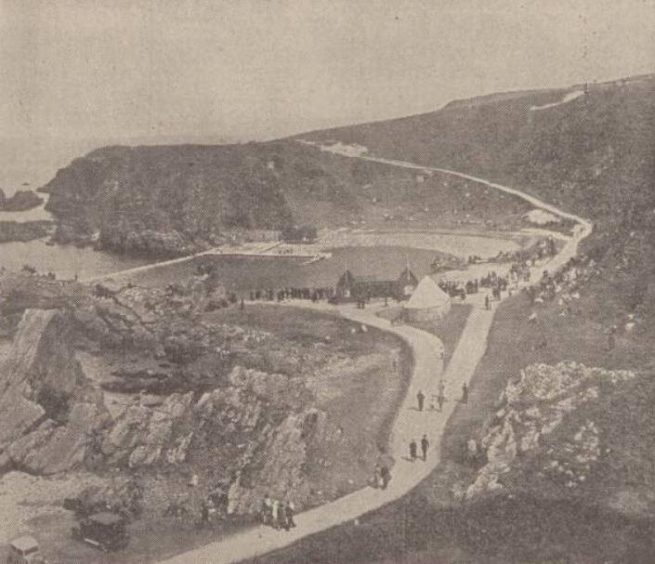

In 1930, a scenic spot had been identified for the new pool at the Howe of Tarlair, a dramatic but beautiful part of the Banffshire coastline.

An update in the Press and Journal the following year read: “Through the efforts of the community and a little aid from the Government, in the shape of an unemployment grant, the council have enclosed a beautiful spot at Tarlair amid magnificent rock scenery.

“When fully finished, it will prove a tremendous attraction to the town as a summer resort, which it is proving to be each successive year.”

On the rocks

But by 1931, the tidal pool had still not materialised.

The project was starting to flounder; government funding fell through.

The grand and much-desired scheme by the rocks was very nearly on the rocks.

At a time when the country was sliding into the Great Depression, government spending on an open-air pool next to the bracing North Sea would have seemed like folly.

Eventually, through the determination of locals and the burgh council, enough funds were scraped together.

Unemployed men contributed their labour to build the platforms on either side, and the efforts meant the outdoor pool eventually opened in July 1932.

“Fairytale surroundings”

“In fairytale surroundings, there arose from an original small sum of £80 Macduff’s pool at the Howe of Tarlair”, wrote commentators.

The town council was applauded for “an outstanding piece of public enterprise” but really it was tenacious John Hird that deserved the praise.

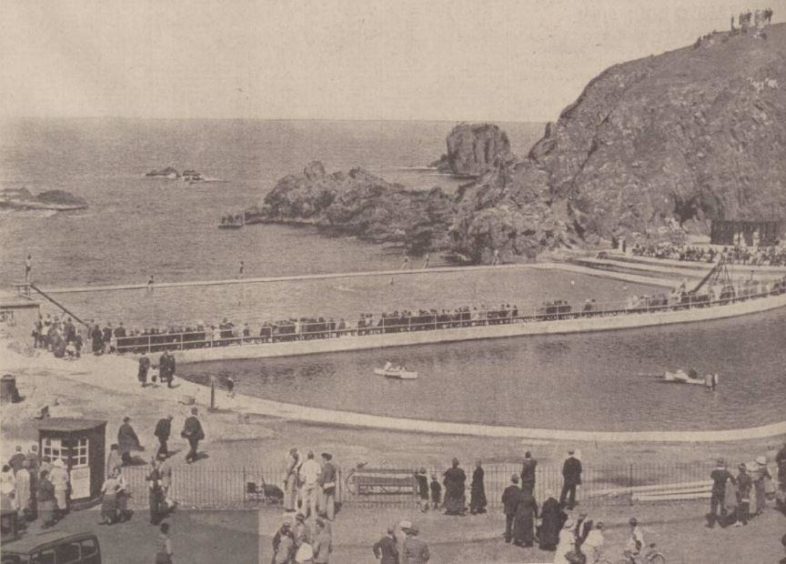

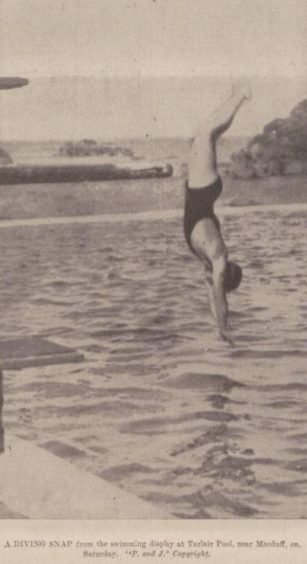

The first-ever gala was held on July 22 1932, a showcase event to debut Macduff’s marvellous new leisure complex.

A crowd of 3000 people – probably more than the then population of Macduff – turned out to watch swimming races and diving demonstrations.

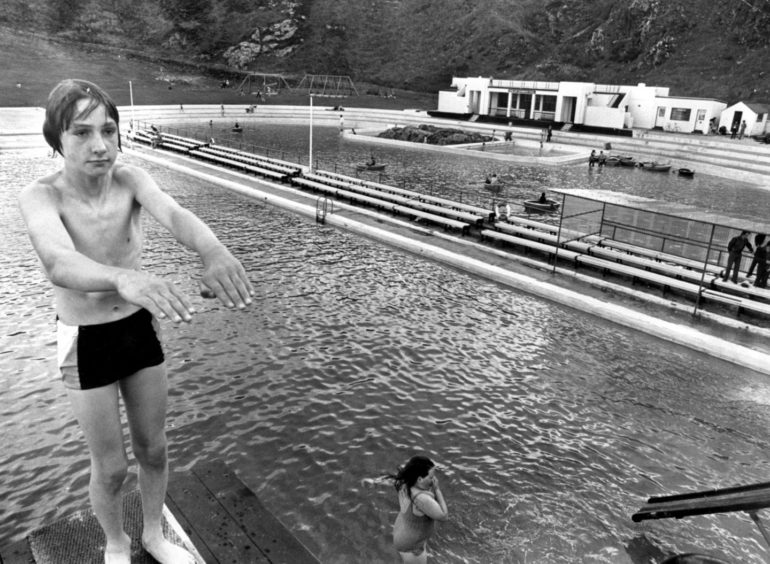

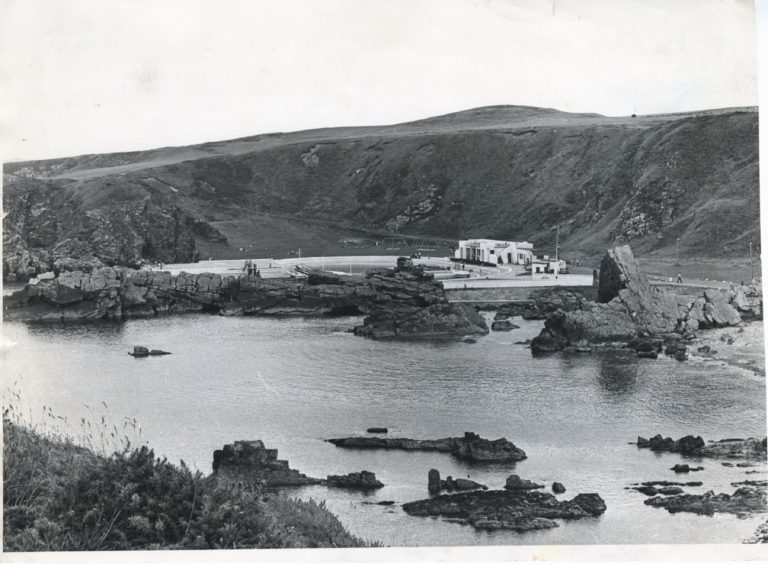

The concrete Tarlair pool was an almost alien structure – it certainly looked other-worldly against the coastal landscape.

The bright and white modern lines of the Art Deco architecture stood in stark contrast to the pitted and craggy black rocks which enveloped it.

John C Miller, the burgh surveyor for Macduff, was the architect behind the project.

The complex initially featured a large tidal pool and boating pond next to the sea, surrounded by curved, stepped walkways.

The boating pond was considered an unusual addition, the only other known example was at Dunbar.

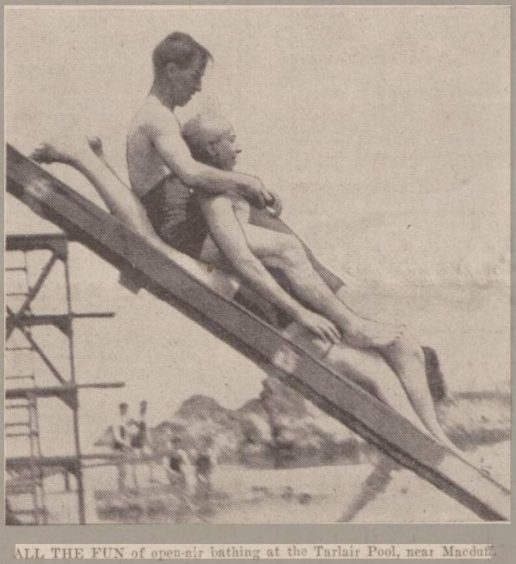

When its popularity took off, a paddling pond and chute were constructed in 1935 for younger swimmers to join in.

A striking and symmetrical rectangular Art Deco tea pavilion was also added that summer season.

It had a three-bay frontage, bookended by two taller pavilions at either end, steps led up to a roof terrace, on top of which Turriff Silver Band played on its opening day.

Bathing boxes, or changing rooms, were added as the complex’s popularity grew in 1933, while fencing was erected in the 1950s.

“Tarlair beats the lot”

In the summer months, the road to Tarlair was said to be nothing but a steady stream of cars, attracting swimmers from far and wide.

On the opening day of the season in July 1935, 700 people paid for entry to the pool and dozens attended a dance in the pavilion that night.

A trailblazer, it was one of the earliest outdoor pools of its kind in Scotland and its popularity only grew as lidos became more prevalent.

The attraction also received high praise from none other than an elderly minister from Banchory, the Reverend D Aitken.

He wrote to the press in 1939 to pass on his compliments, declaring: “I have been in a number of swimming pools both in this country and abroad, including Toronto.

“Even including pools constructed for millionaires, but Tarlair, for setting, and for purity of water beats the lot.

“Some pools are heated, and some are too cold, but Tarlair is just right.”

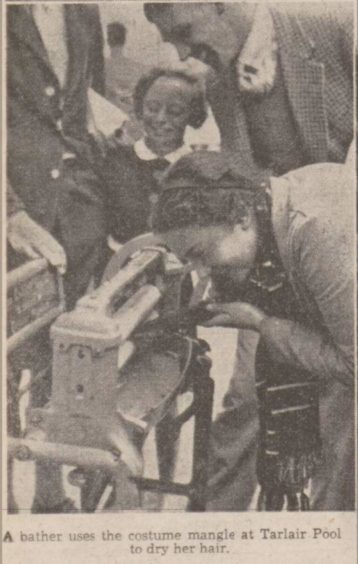

The seawater was indeed pure – after bouts of stormy weather, pond attendants had to scoop legions of jellyfish from the water.

But the Second World War was just around the corner and as the conflict rumbled on, it was decided not to open the pool complex in 1941.

The pool reopened for subsequent seasons, only gaining popularity as people holidayed closer to home.

And the happier post-war years saw record visitors, with 1949 hailed as the best season yet.

Record crowds

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, the pool hosted swimming contests from which attendees came from all over the region to compete in.

Including the annual north-east swimming competition for the coveted Duthie-Boothy Shield.

1950 saw a record crowd of 6,000 spectators watch Elgin Amateur Swimming Club’s Tarlair debut, while Banff Pipe Band entertained during the intervals.

In 1952, Charles Reid of Stonehaven was appointed as Tarlair’s pondmaster.

A champion swimmer, instructor and lifeguard, at the age of 22 was the youngest man in Scotland to be put in charge of a swimming pool.

Despite the increase of foreign travel in the 1960s, the draw of Tarlair and its pleasant waters did not wane.

The summer of 1966 was a world away from the simpler times of the 1930s.

Footage of Banffshire from 1962 featuring a busy afternoon at Tarlair.

The rebellious Rolling Stones were in the charts, but still 38,000 people – and droves of teenagers – visited Tarlair that summer.

And by the end of the decade it was still a profitable enterprise taking in thousands between admission and the tearoom.

Tide turning on Tarlair

History was made at Tarlair in 1972 when 19-year-old University of Aberdeen student Alison Ross was appointed as the first ever pondmistress.

But the pool still struggled to keep up with the times.

As the years wore on, outdoor swimming clubs fell out of favour as heated, indoor facilities became preferable.

And swimming competitions that once attracted thousands were only receiving a handful of competitors.

By 1975, the pool was no longer under the control of the town council, instead the new district authority, after a shake-up in local government.

That year saw the most disappointing season opening yet.

Marred by bad weather, only 80 people turned out for the pool’s official opening.

By now, the lido was more than 40 years old and in need of serious maintenance with £60,000 estimated in alterations and improvements.

But funding from the Scottish Education Department to local authorities was slashed, and with it went any hope of funding Tarlair’s repairs.

Storms caused further damage in the late 1970s and the local business association appealed to the council to step in.

In 1978, the group highlighted their shock at the state of the crumbling pool walls and changing rooms.

In an impassioned plea, they wrote “Tarlair is worth saving and must be saved”.

Money dried up

But little changed, and by the 1980s the district council suggested the pool had “outlived its usefulness”.

The claim was fiercely contested by the local community council who said the pool was being deliberately run down when it instead should be upgraded and promoted as a tourist attraction.

An in-depth study in 1988 found that nearly £100,000 would be needed to repair the leaking facility, money the council did not have.

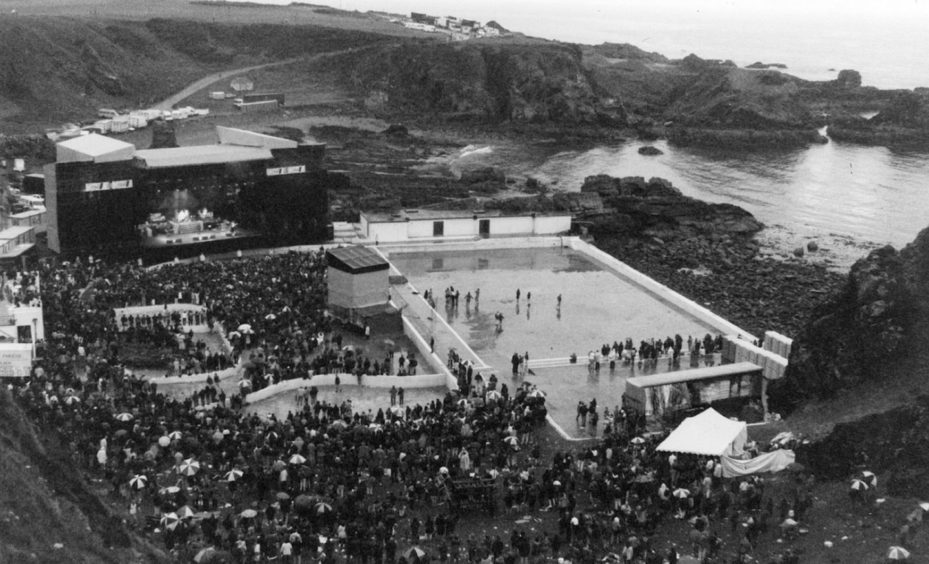

A compromise was reached to carry out the most urgent repairs and talks turned to other uses, including as a concert venue.

A Live-Aid style rock concert had been held at Tarlair in 1985 for famine relief, and its success inspired an annual Macduff music festival for charity.

Firmly established as a top music event by the 1990s, the 1994 sell-out festival weekend saw 5,000 people packing into the empty pool to watch Runrig and Wet, Wet, Wet.

Wet, Wet, Wet – who were in the midst of a marathon run at the top of the charts with Love Is All Around – arrived by helicopter and were mobbed by waiting autograph hunters.

Thousands packed into the pool to watch the chart-toppers, and the gig was a huge success, despite the rather (ironic) wet weather.

But the pool sank further into disrepair and further council cuts in 1996 saw it closed along with Stonehaven’s outdoor swimming pool.

“Outstanding example of pool”

Although Stonehaven’s outdoor pool was saved from a watery grave, Tarlair has continued to decay in recent years.

But amid the ruin there is still beauty, and the site’s uniqueness earned it category A listed status from Historic Scotland in 2007.

In its statement of special interest, the heritage body said: “A remarkably fine, little-altered and early example of an outdoor Art Deco swimming pool.

“It is one of only three known surviving sea-side outdoor swimming pool complexes in Scotland, and certainly the one that best retains its original appearance.

“Although the buildings at Tarlair are relatively modest, the pool itself is impressive with the generous curved sides of the boating pool, and swimming pool beyond.”

It also highlighted that the appearance of the pool has changed little from 1935 and “its state of intactness, simple yet stylish design, early date and magnificent location all contribute to make this pool the outstanding surviving example of its type in Scotland”.

Tarlair’s lido was also added to Scotland’s Buildings at Risk register in 2008, and is considered to be in “very poor” condition and at “high risk”.

Sea-change on the horizon?

There has always been a strong desire in the neighbouring community to see Tarlair preserved.

And now, as the pool marks its 90th year, there is a glimmer of hope on the horizon.

The Friends of Tarlair group formed in 2012 with a view to restoring making Tarlair safe.

In 2013, the council commissioned conservation and design engineer John Addison to assess the precious site.

£300,000 of authority-funded conservation repairs in 2015 made the complex safe for walkers and model boat enthusiasts.

But there were no funds left to progress phase two, renovating the pavilion, and now the group hopes to fundraise the £915,000 needed to continue their valiant project.

In addition to fundraising and building a business case, the dedicated volunteers work year-round carrying out maintenance and clearing seaweed.

Further progress was made in 2020 when the Friends took on a 99-year lease of the pavilion block, with the future aim to return it to full community use.

Once the pavilion is restored and profitable, it is hoped the funds from it will help pay for the complete restoration of the complex, and bring some sparkle back to this rare gem.

See more like this: