She was the Ukrainian-born child who learned to love Robert Burns and became one of Scotland’s most cherished sports personalities.

Even now, seven years after Elena Baltacha died of liver cancer at the age of just 30, she is remembered with fondness throughout the tennis world by everybody from Andy and Judy Murray to Billie Jean King.

It’s 20 years ago this summer since the teenager first paraded her talents at Wimbledon and, although she was forced to battle with illness from those formative years all the way through to her premature demise, she kept smiling, refused to look for sympathy or excuses, and beamed a transcendent smile to millions of players, officials and fans on her global travels.

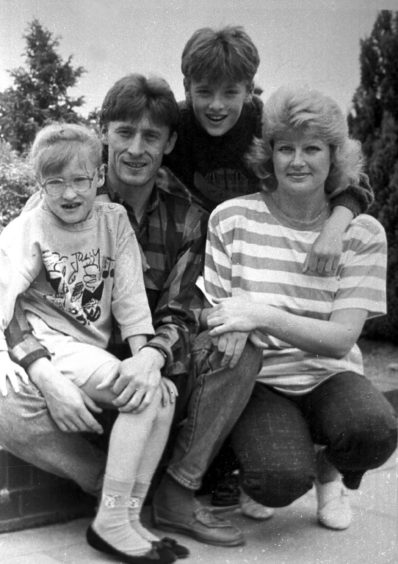

From the outset, she was “Bally”, the daughter of international footballer, Sergei Baltacha, whose peripatetic career brought him from the old Eastern Bloc to St Johnstone and then Inverness Caledonian Thistle.

It might have been a culture shock for some youngsters, but not this mixture of sporty and ginger spice who began making waves in the early 1990s.

Judy never forgot Elena’s debut

Judy Murray has coached and mentored thousands of players in the last three decades, yet few made such an immediate impression as Baltacha.

The introductions came in 1993 when the woman who nurtured Andy and Jamie to all manner of Grand Slam victories and Davis Cup success met a confident young girl with ginger hair, a cap and big glasses.

She said: “She won the tournament and her thumping serve meant she lodged the balls in the hedge – which upset her opponent in the process.

“It was an indicator of her natural strength. You know, little girls aged nine just do not serve like that.

“She was just really generous of spirit and yet, if you watched her playing tennis, you would see a ferocious competitor who looked as tough as nails. It’s almost as if there was this split personality.”

The signs were there from the start

Anybody who attended mini tennis tournaments in the Highlands at that time soon grew familiar with the sports-daft family and not just because of Sergei’s skill on the football pitch or the athletic prowess of his wife, Olga.

Her coach in Perth, Jimmy Mackechnie, was thrilled by Bally’s development and later reminisced not only about her Wimbledon debut with a match on Centre Court against France’s Nathalie Dechy, but also the fashion in which she demonstrated how quickly she had adapted to her new surroundings by convincingly reciting the poetry of Scotland’s national bard.

He said: “I remember looking at the nine-year-old Elena. She had big, round-rimmed glasses and a baseball cap and she hit the ball harder than anyone I had ever experienced from somebody of that age.

“She trained with me every day for seven years and I saw her progress from a young girl into a young lady. I saw her win her first Scottish under-12 championship, then the women’s title at 15. She was absolutely fearless and the influence she had on the game in Scotland was huge.”

Wimbledon was just the start

The teenage prodigy hadn’t been expecting to launch her career at SW19 in such an exalted setting. Even a few hours earlier, she had been steeling herself for a trip to one of the outer courts, away from the spotlight.

But fate intervened on her behalf and she was suddenly in the media glare.

Mackechnie explained: “Her wild card at Wimbledon at 18 was the culmination of a determined journey. The previous match on Centre Court had finished early and Elena’s match was switched late on.

“She was very nervous and she got quite emotional before she went on court. Yet it was something she had trained for and she took to it like a duck to water. She always gave 100% and, in life, if you do that, then no-one can ask any more of you. She was competitive, powerful and a role model.”

Friends and rivals alike marvelled at her commitment as she climbed into the world’s top 50 throughout the next decade, while reaching the third round at Wimbledon and the Australian Open in 2002.

But, off the court, she was struggling with illness and regular aches and pains and was eventually diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a liver condition which caused extreme lethargy and fatigue.

Undaunted, she lifted up her racket and carried on.

Elena joined the Murrays in Aberdeen

Baltacha had shown a relentless work ethic as she steadily climbed the global rankings and was among a new generation of Scots who became accustomed to journeying to tournaments with realistic hopes of success.

She joined up with Andy and Jamie Murray when they tackled England in the Aberdeen Cup events in 2005 and 2006 – and while it was the younger Murray brother who gained banner headlines, they were boosted by Bally’s high-octane approach in these special challenge matches.

She was still toiling with bouts of illness, but her joie de vivre in and around the sport was admirable. In Aberdeen, she talked about setting herself little milestones, propelling herself forward even if it meant pushing her body through the wringer. And she was typically honest about her contrasting fortunes at Wimbledon in the early stages of her career.

A victory for the ages

She recalled: “In 2001 I was so nervous – I couldn’t believe that I had been put on Centre Court for my first match as a senior at Wimbledon, and I think I lost the first set 6-0 in something like 20 minutes.

“But it was still a great experience. Unbelievable. Something you dream about.

“Then in 2002, when I defeated [South Africa’s former world No 3] Amanda [Coetzer] it was the result that was unbelievable. I had so many people behind me and giving me encouragement that it was like a dream.”

This was in the days of Henman Hill and prior to Murray Mound. You might describe it as a time of Bally High! They offered consolation for the lows with which this resilient character had to grapple as she moved into her late 20s.

It’s all about believing in yourself

And yet, there was immense satisfaction and no shortage of pride when she was selected for the GB team for the Olympic Games in London in 2012.

It was Judy Murray who broke the news to Baltacha and allowed her to follow in the footsteps of her parents, who both appeared in the Games for the USSR.

For the next few days, Baltacha was involved in one of the greatest pageants which she had ever experienced. She was enthralled by the spectacle, but her professionalism meant she practiced incessantly before the torch was lit.

As Judy said: “If you wanted somebody to lead your team and you wanted somebody to be a great role model as a British No 1, both on and off the court, then you would pick her every time.”

The candle burned out far too soon

In advance of the Olympics, Baltacha spoke about the litany of injuries and illnesses which had marred her career. But she remained upbeat.

She said: “I am more consistent now, performing regularly week in, week out. In the past, I would have a great week, or two weeks, and then go off the boil a bit. Now I feel more stable as a player.

“I know I’ve got the liver condition for the rest of my life, and I still have to take medication for it, but it doesn’t affect me now. It’s under control.”

She seemed in a happy place when she married her former coach, Nino Severino, in 2013. But, as he told the BBC in a programme in 2019, the joy and affection at the ceremony masked some grim issues in the background.

He said: “She wasn’t feeling very well, but we thought that she had a virus because none of the medical people had picked it up. However, on the day of the wedding, she was suffering quite a lot.

“The wedding was the best day of our lives, it was something that Bally wanted so much, to be married. She arranged all the wedding and it was a fairytale for both of us. She was beautiful, absolutely beautiful.”

But, just a few weeks later, at the start of 2014, Baltacha was diagnosed with terminal cancer of the liver. Four months later, she was gone.

Andy Murray’s tribute was heartfelt

There were tributes from every corner of the globe, allied to expressions of shock as the suddenness of her passing.

Andy Murray, who defeated Nicolas Almagro in straight sets at the Madrid Open the day after her death, walked over to a TV camera and signed the lens with the word ‘Bally’, drawing a heart around her nickname.

Later, he talked about the person for whom he had a stratospheric regard.

He said: “Tennis is a small community, a small world. And, in small worlds, you can usually get a good sense of what everybody is like.

“You hear things. And trust me: when somebody is a ‘bad apple’, in any way, you are definitely going to hear things.

It was a shock beyond shock

“But Bally – all you heard were the best things. Honestly. Just how gracious she was, how easy she was to work with and how nice she was to anyone she interacted with. She was just…a good person. My mum coached her from a young age and she was very fond of her. We all were.

“When she succumbed to it, and died at 30, it was a shock beyond shock. I could try to find the words, but I wouldn’t manage. It was hard to process.”

Nobody who met her ever forgot it. Jimmy Mackechnie is among those who believes it was a privilege to work with Baltacha in the early days.

He said: “My fondest memories of Elena will be seeing her walk out onto Centre Court. Away from tennis, when she was 12 or 13, she recited to me one of Burns’ poems. By that time, she had developed quite a Scottish accent.”

And, in so many ways, this woman did Scotland proud.