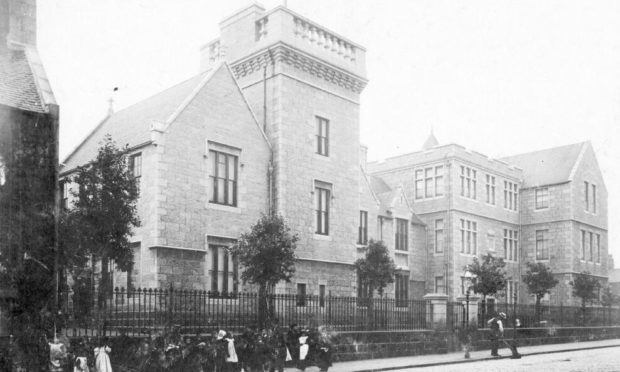

Causewayend School was a regal presence in the community of Mounthooly for 131 years from 1877 until its bitter closure in 2008.

But when it was built, Aberdeen’s well-to-do questioned why the school board had built such a magnificent building in part of Aberdeen they described as “a gutter”.

With more than a passing resemblance to Balmoral Castle, the Victorian school was designed in the Scots Baronial style by Aberdeen architect William Smith.

Smith had been commissioned by Prince Albert to design the new Balmoral Castle in 1852.

And when it later came to designing the east end’s new school, he brought a touch of majesty to Mounthooly.

A report from 1877 described the school as “a strikingly handsome structure, set down as it is in a neighbourhood entirely neglected in the matter of adornment, stands out in bold relief against the neighbouring buildings, all of which are put completely in the shade by this new home of learning”.

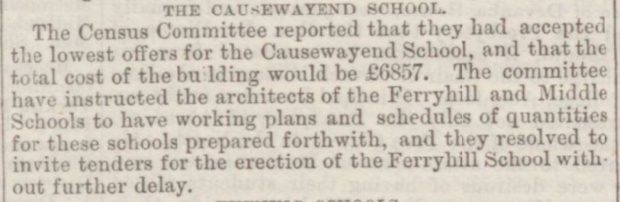

For the princely sum of £6857, Smith’s vision was brought to life, complete with a square tower, balustrades, battlements and a cylindrical tower with a flagstaff.

Added to the £1817 needed to purchase the land on which it was built, Aberdeen School Board worked out that the equivalent cost per pupil was £9 and 16 shillings.

The board told Aberdonians that, at a total sum of £8674, citizens got a bargain at a time when Aberdeen was fast expanding, and materials and labour were expensive.

Serving city’s poor

Designed to accommodate 700 children based on a calculation of 8-square-foot of space per child, the school was already at capacity when it opened.

Causewayend School’s first day on February 12 1877 saw 680 girls and boys file through the gates.

It was built at a time when families had multiple children, and the Mounthooly area on the edge of the city centre was densely populated.

Causewayend was just the second of five schools needed to meet the requirements of the population of Aberdeen under the 1872 Education (Scotland) Act, which made school compulsory for the first time.

It was recognised that something had to be done for the “educational wants of a large and growing district, chiefly occupied by the working classes”.

The catchment included Spring Garden, the north end of Gallowgate, Hutcheon Street and George Street.

Castle in a ‘gutter’

The ceremonial opening on February 1 – practically fit for royalty – was attended by the Lord Provost, city magistrates, county sheriffs, the city clergy, the school board and a large gathering of the public.

The imposing school – with its large, lofty classrooms spread over three spacious floors, state-of-the-art ventilation systems and sanitary provision – raised eyebrows.

Aberdeen’s well-to-do ruling classes made no attempt to hide their impression of the working classes.

One dignitary asked how men could “put down a building such as this in such a place”.

And there was laughter when asked what was wrong with the location, one man quipped “we are putting down a large castle in the midst of a gutter”.

Education board chairman Professor Black responded: “I venture to say that a more admirable site for a school could not be chosen.

“It is precisely in the centre, or as nearly as possible in the centre, of the people for whose benefit the school is intended.

“I don’t know that anyone has a right to speak of this part of the town as even a low part.

“And I think we have done one thing if we have done nothing else; we have thrown light and beauty, architecturally speaking, into a part of the city that perhaps required it as much as any.

“I must admit it is a somewhat expensive building, but it is a substantial building, and will last many generations.”

Causewayend’s curriculum

Causewayend School’s first headmaster was John McLachlan, and the school operated on a ‘mixed principle’.

Boys and girls were taught together, but had separate entrances.

As well as a focus on literacy and grammar, Mr McLachlan encouraged his pupils to enjoy drawing, both in a creative manner and in technical geometry.

Another curious addition to the curriculum was teaching sewing to infants.

The school was unusual for the era in that rolls showed some pupils were as young as three, while others stayed on until beyond the age of 14 – the Scottish leaving age in 1893 was 11.

And Aberdeen School Board was also ahead of its time, banning the use of the cane as corporal punishment in 1881, but the strap would still be in use for another 100 years.

Predictably, by 1913, the school was bursting at the seams.

Four classes each had 80 pupils in them, and some senior classes were taught at a nearby church hall.

The following year the school leaving age was officially raised to 14 across Scotland.

But despite the overcrowding, Causewayend’s inspection reports were favourable, branding the school as “on the whole, very satisfactory”.

Wartime work

When war broke out in 1914, the youngsters willingly contributed to the war effort, even though many came from poor homes themselves.

French soldier Jean Guilbailt wrote to Causewayend pupil Jeannie Morrison, of 40 Powis Place, from the frontline to thank her personally for a care package she had sent to France.

Jeannie had sent socks, mittens and cigarettes, and received the response:

“While passing through a station, your nice little parcel was handed to me, as well as your kind letter. It gives me much pleasure to thank you sincerely for your kindness.”

Causewayend youngsters were again poised for action upon the outbreak of the Second World War.

Aberdeen schoolchildren were tasked with gathering nettles for the Department of Health to be turned into medicine.

Causewayend School was designated as a clearing station, and all the nettles collected across Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire were sent there to be hung up and dried.

A voluntary staff of scientists and helpers stripped the stalks and selected leaves to be sent to chemists in England for manufacturing – the value being in the iron they contained.

A report praised Causewayend pupils for being “the most enthusiastic collectors” who went daily to the outskirts of town to collect nettles.

The area suffered greatly during wartime raids and after a particularly bad bombing in 1943, the school was one of few buildings untouched in the district.

The school log reported that the blitz had left 120 pupils homeless.

Facing the axe

In 1970 Causewayend welcomed Mrs Youngson, its first female headmistress, after a run of 10 male heads.

The days of overcrowding were long gone as pupils moved up secondary school at 11, instead of staying on until 14.

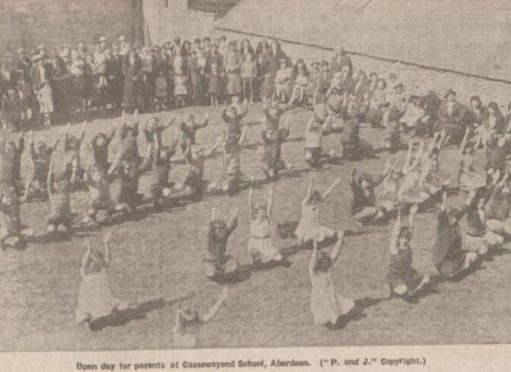

A much more manageable roll of 250 created a “family spirit”, and the school continued to innovate.

An old outbuilding was turned into a domestic science block, where P7 boys were taught how to cook as well as girls, something Mrs Youngson said the boys loved.

In 1972, former pupils were invited to share photographs and documents of the school’s past to help mark the centenary of Causewayend’s importance as one of the five city schools built under the 1872 Education Act.

But the 1970s brought challenges.

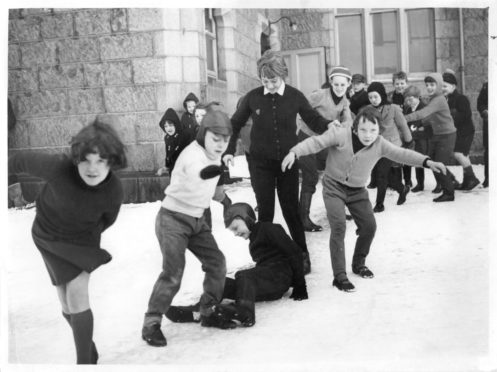

Scholars suffered years of disruption as the community of Mounthooly was flattened around them, and a chunk of the playground was lost to the new dual carriageway.

But there was shock and sadness in 1980 when Causewayend was earmarked for closure, along with seven other city schools due to falling rolls.

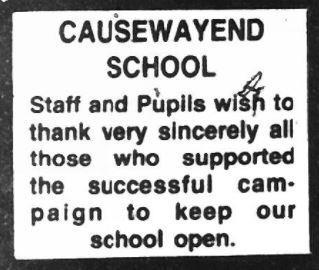

Each of the school’s 155 pupils wrote to the council’s education committee begging to keep it open.

And after one of the biggest protest campaigns mounted in the city until that point, Causewayend and Cummings Park schools were granted stays of execution.

The Scottish Secretary stepped in to overrule the council.

Balnagask, Inverdee, Rosewood, Burnside, Willowpark and King Street Primary were not so lucky.

Robert Hughes, Labour MP for North Aberdeen, said it was “the beginning of the end for a unique Scottish educational system”.

Threat of closure

In 2003, the school celebrated its 126th anniversary with a cake in the shape of its famous ‘Balmoral tower’.

Pupils past and present helped mark the milestone, but within months there were talks of another education review.

A host of schools were identified as having falling roles, as families moved from the city to the shire.

By 2004, the future of Causewayend was more uncertain still when it made a shortlist of schools at risk of closure.

Years of bitter campaigning and political rows ensued between the ruling SNP/Liberal Democrat administration and the Labour opposition.

Then Labour education spokesman Neil Cooney said schools which had “survived the Nazi attacks could be lost” under the proposals.

While former city MSP Lewis Macdonald urged the council to “stop picking on inner city schools”.

But the administration defended the move citing the need to make £27 million in savings.

In August 2008, furious parents vowed to “fight to the end” to save Causewayend and four other stricken schools, and marched to Aberdeen Town House to demonstrate.

‘Aberdeen assassin’, former boxing champion Lee McAllister, added weight to the campaign.

But despite the public’s “unanimous rejection” of the council’s plans, a report leaked to the P&J in April 2008 revealed the battle was all but lost.

Even threats of a legal challenge from parents couldn’t stop the axe falling on Causewayend.

There were tears as pupils said goodbye at the end of the summer term in July 2008 – youngsters performed songs they had written for a special assembly.

After the doors shut on 131 years of history, Causewayend sat decaying for years, repeatedly targeted by vandals and firebugs.

Recognising its architectural merit as a C-listed building, any future proposals had to retain and reuse the main school building.

Student accommodation provider Unite came forward with plans to transform the old school into flats.

Completed in 2016, it is apt that today Causewayend – one of the city’s first seats of modern education – should continue to house scholars, albeit university students.