Hit new Scottish BBC drama series about nuclear submarine HMS Vigil has had viewers gripped with its thrilling tales of death and intrigue in the depths of the sea.

The star-studded six-part police series focuses on events surrounding a shocking and mysterious death aboard a Royal Navy Trident nuclear submarine.

Suranne Jones is lead detective DCI Amy Silva who is deployed to the boat to conduct a solo murder investigation.

She is backed up by her tenacious colleague DS Kirsten Longacre, played by Aberdeenshire actress and Game of Thrones star Rose Leslie.

Line of Duty’s Martin Compston and Endeavour’s Shaun Evans are sailors Craig Burke and Elliot Glover, part of the closed-rank crew, suspicious of outsiders, aboard a submarine where nothing is quite as it seems.

But when it comes to the secretive, murky world of submarine warfare, is the truth stranger than fiction?

Is HMS Vigil a real nuclear submarine?

Filmed in Scotland, producers World Productions have been clear that HMS Vigil and its storylines are entirely fictional.

However, the boat is based on the Royal Navy Submarine Service’s (RNSS) Vanguard-class nuclear submarine and the controversial Trident nuclear deterrent programme, which oversees the operation of nuclear weapons in the UK.

Britain’s Vanguard class, built between 1986 and 1999, is made up of four submarines: Vanguard, Victorious, Vigilant and Vengeance.

Each boat is armed with torpedoes and up to 40 Trident nuclear warheads.

All four submarines are 150 metres long, powered by Rolls-Royce nuclear reactors and are based at HM Naval Base Clyde near Glasgow.

Nicknamed ‘the silent service’, the Navy’s submarine fleet is hidden below the waves where, undetected, it tracks and monitors other submarines, boats and aircraft.

Britain first introduced Resolution-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) from 1968, which were replaced by the current Vanguard-class and Trident from 1994.

Did a submarine really sink a trawler?

But the similarities between Vigil and real-life events doesn’t end with the submarines themselves – it comes a lot closer to home.

The dramatic series opener shows a fishing trawler being dragged into the depths by its nets in the vicinity of HMS Vigil, which is lurking in the Atlantic off the coast of Scotland.

Footage shows fictional fishing boat Mhairi Finnea near the Outer Hebrides, before the vessel and its crew are violently pulled underwater to their deaths.

Despite the insistence of Compston’s character Burke to go looking for the crew, he is overruled by higher command and told to proceed with the mission.

The tense scene bore many parallels with a true-life tragedy – the sinking of the fishing trawler the Antares by a Royal Navy nuclear-powered submarine in 1990.

The Antares was a small pelagic trawler built in the Aberdeenshire fishing village of Sandhaven during the 1960s, but its home port was Carradale on Kintyre.

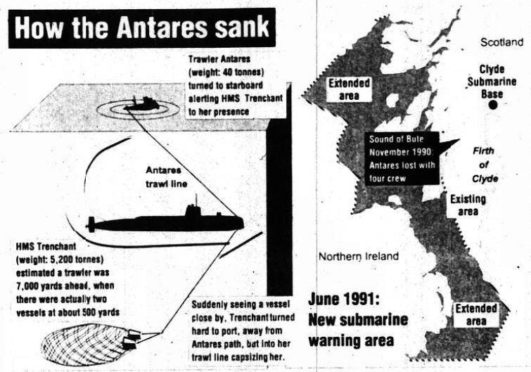

In the early hours of November 22 1990, the Antares was brought down by HMS Trenchant, killing its four crew, all from Carradale and Campeltown.

The vessel – with skipper James Russell, Billy Martindale, Dugald John Campbell and Stewart Campbell on board – had gone to a deep water area of the Firth of Clyde known as the Arran Trench for some overnight trawling.

The last known contact the Antares had with the mainland was at 10.30pm when the captain phoned home to say all was well.

But HMS Trenchant was also gliding through the depths of the firth carrying out a perisher training course with new recruits.

Submarine crew reported hearing a loud clattering, but when rising to periscope level saw two fishing boats quietly bobbing above that did not appear to be in distress.

Upon surfacing, nets and chains were found entangled on Trenchant’s hull, but not seeing any signs of an incident, the crew assumed they had become entangled in spare nets and carried on with their training.

What happened to trawler the Antares?

It was not until 8am that morning that alarm bells began to ring.

Hearing about the submarine’s incident involving nets, the Clyde Fishermen’s Association began contacting ports and boats to ensure all vessels were accounted for.

It quickly became apparent the Antares had not returned home, and a land, air and sea search was launched to find the vanished vessel.

Only a small amount of debris and oil was spotted initially, but the following day sonar picked up a new wreck on the seabed.

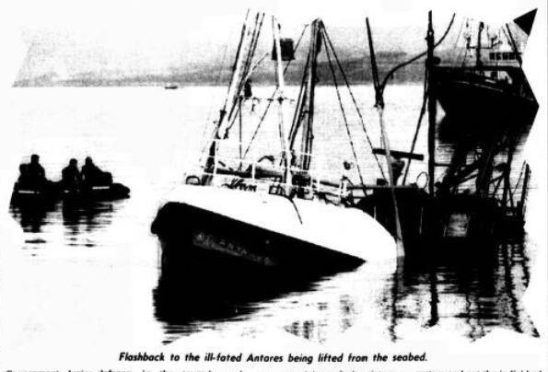

The Antares’ wreck was raised and inside were the bodies of three of the four crew.

Prolonging the families’ agony, it would be another year before the fourth fisherman’s body was found, brought up in the nets of another vessel.

A 12-day inquiry in 1991 blasted the Navy for a catalogue of failings.

The probe revealed HMS Trenchant had dragged the Antares to the seabed and not carried out a proper search for survivors.

In his findings, Sheriff Principal Robert Hay said that two of the drowned fishermen could have survived.

He added: “Both could swim and may have been alive for some time on the surface after the sinking.”

The sheriff condemned the Navy for failing to bring HMS Trechant to the surface for 30 minutes after the incident and that the submarine had already had a “close pass” with another vessel that night, which was not reported to officers.

He said the Navy “fell short of the standards to be expected of seafarers” and that there was “serious human error”.

A policy of mandatory separation zones of at least 3,000 yards between submarines and fishing boats was immediately introduced, and welcomed by the families.

Speaking at the time, the skipper’s widow Christine Russell said the findings were fair and that the tragedy was “the fault of a system and not an individual”.

But she echoed wider calls for a midweek ban on submarine activity in the Clyde.

A new code of practice was brought in for submariners based on recommendations from the inquiry.

Despite the similarity between the Vigil storyline and the Antares tragedy, the BBC reiterated it is “a fictional drama and is not inspired by or based on any specific real-life events”.

Can a submarine lose power?

In episode two, while DCI Silva is desperately trying to interview a stand-offish crew, HMS Vigil suffers a catastrophic power failure.

It was panic stations as the submarine entered emergency shutdown mode with only enough back-up power to last three hours.

The shutdown was caused by a reactor scram – the stoppage of a nuclear reactor which prevents the fission reaction taking place.

With time running out and no obvious reason for the reactor failure, the desperate crew face having to surface using diesel power.

But it was a decision that would risk making themselves visible to potential enemies.

As it happened, the sailors managed to restart the reactor and the submarine was able to descend to the depths, avoiding a collision with a tanker – and any enemy encounters.

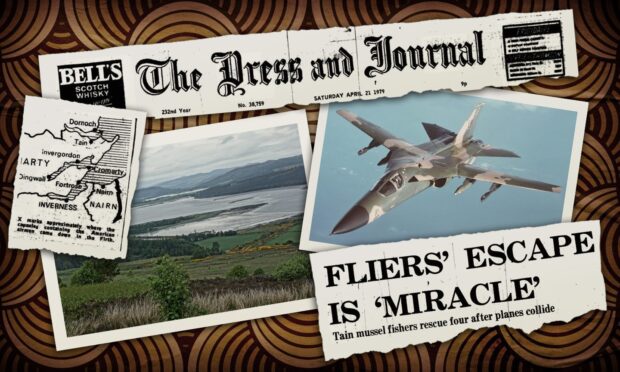

But in 1978, a Soviet submarine wasn’t quite so successful in maintaining its stealth.

A reactor failure on board a Soviet Echo II class nuclear cruise missile submarine forced it to surface north of Scotland near Cape Wrath on August 19 1978.

Operated by the pacific and northern fleets of the Russian Navy, its 29 Echo II class submarines were built between 1962 and 1967 as anti-carrier missile vessels.

The power failure on the stricken submarine meant it had to surface using diesel power, and was immediately spotted and shadowed by US marine intelligence forces.

The armed submarine was escorted east by a Soviet missile cruiser, missile destroyer and a tug as it limped out of UK waters and back to Murmansk on solid fuel.

At the time, UK reports said “news that this class of submarine could have auxilliary diesel engines caused a ripple of surprise in Western naval intelligence”.

Could submarines collide underwater?

There have been hints that HMS Vigil is being tailed by enemy forces while creeping around the Atlantic.

And there were concerns it was an enemy submarine that was close enough to Vigil to have brought down the trawler above.

In November 1974, two submarines were close enough to collide off the west coast of Scotland – although the secret incident was only revealed in 2017.

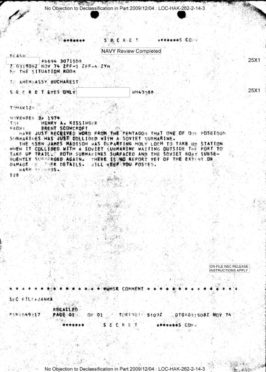

A declassified CIA document showed that two nuclear submarines crashed near the Firth of Clyde at the height of the Cold War.

US and Soviet submarines routinely tracked each other and there had always been speculation about prangs.

A cable message to then US secretary of state Henry Kissinger labeled “secret eyes only” detailed a collision between American and Russian submarines near Holy Loch, then a US naval base.

The extent of the damage was not disclosed, but the US submarine SSBN James Madison had to be taken back to base for repairs to its hull.

The memo read: “Have just received word from the Pentagon that one of our Poseidon submarines has just collided with a Soviet submarine.

“The SSBN James Madison was departing Holy Loch to take up station when it collided with a Soviet submarine waiting outside the port to take up trial. Both submarines surfaced and the Soviet boat subsequently submerged again.”

In more recent times, a submarine grounded off the west coast of Scotland during sea trials on October 22 2010.

HMS Astute, a flagship submarine, strayed out of a navigational channel near the Skye Bridge and struck the seabed close to shore.

She had to be pulled to safety by a tug after the incident which led to a high-profile public inquiry.

The probe found that a series of errors caused the grounding and that the commanding officer was in the shower when the boat was edging closer to shore.

While the officer on the boat’s bridge was not using the correct radar and was unused to navigating in the dark.

A number of safety recommendations were made which the head of the submarine service accepted.

See more like this: