I like maps. I always have done. Within reach of my desk in what passes for my home office is a long-ago Christmas present, ‘The Reader’s Digest Great World Atlas’, published in 1962 and, though a bit battered, still usable and used.

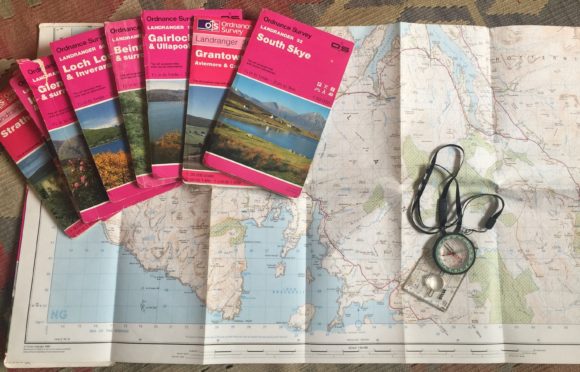

But if my near 60-year old atlas is consulted on occasion, the maps I turn to more often are quite different. They’re produced by the Ordance Survey. There are over 200 in total. And they cover all of Britain on a scale of 1:50,000 – more easily understood perhaps as one-and-a-quarter inches to the mile.

Each map in this Landranger series has a red cover with a photograph showing a scene from the area it deals with. They’re numbered north to south. Landranger 1 shows Unst and Yell in Shetland. Landranger 204 shows the part of Cornwall that’s centred on the town of Truro.

The highest-numbered map in my possession is Landranger 137, Church Stretton and Ludlow, bought when on holiday in Shropshire. But it’s an outlier. Most of my Landranger maps show one piece or another of the northern half of Scotland – where I’ve mostly lived, where I’ve mostly worked and where I’ve travelled nearly every road.

Now that such travelling is forbidden, my OS maps are a sort of key to replaying some familiar journeys in my mind.

Here, for instance, are Landranger 10 and Landranger 16. Between them, they show the 45-mile stretch of single-track road – one of the longest such stretches in Scotland – between Bettyhill and Lairg.

Once, back in the 1980s, I drove south along that road on a winter’s morning when, before dawn, there had been a slight fall of snow. Traffic news bulletins on my car radio were dealing, as always at that time of day, in jams and hold-ups and congestion. But it was clear from tyre-tracks in the thin snow layer on the road that, between Syre and Altnaharra, rush-hour had consisted of just two vehicles – my own and one other.

Sometimes on that road I stop at a spot you’ll find near the northern edge of Landranger 16. Once there was a little village here – a village called Grumbeg. Leave your car and climb the slope above the road and you’ll find the scattered stones that are its remnants.

From here there’s a fine view across Loch Naver, a pretty hefty chunk of water, to the high ridge rising steeply to the summit of Ben Klibreck. Just about everything on that far side of the loch is now inside the boundaries of what’s called, more bureaucratically than poetically, Wild Land Area 35.

Although Wild Land Area 35, as that designation indicates, is today unpopulated, it wasn’t always so. More or less opposite Grumbeg was a long-established farming settlement called Achoul. Among its last residents were an elderly couple, William and Janet MacKay, who, when turned out of their home in the early stages of the Sutherland Clearances, were taken in by their daughter and son-in-law whose home was in Grumbeg. Janet MacKay was to die there. But William, her husband, now in his nineties, would be evicted for a second time when Grumbeg, like Achoul, was emptied of its people.

But not everywhere in the Scottish north and north-west is so unoccupied as Sutherland’s interior. Landranger 18 and Landranger 22 conjure up for me a trip that takes me past or through the many crofting townships on North Uist’s Atlantic coast. At Clachan, I could head east for Lochmaddy. But instead I push on south, in my imagination, across the causeways linking North Uist to Grimsay and Grimsay to Benbecula.

By sticking to the more inland of Benbecula’s two main roads, I’ll get a glimpse of a view that’s stuck firmly in my mind since I first saw it in the early 1970s. As you’re getting near Creagorry, you look out on the north end of South Uist. Over there are Iochdar’s croft homes strung out along an unusually flat skyline – looking, as someone has written, like a line of ships seen far out on the sea.

And one last change of scene – courtesy of Landranger 45. This shows the road that takes you across the Dee at Banchory and then, by way of the Cairn o’ Mount, to Fettercairn in the Mearns.

This road’s northern section traverses the parish of Strachan – which, as one of its nineteenth-century ministers commented sniffily, is ‘commonly pronounced Straan’. And Strachan, from as far back as the 1740s, was home to several generations of my wife’s forebears.

Their name was Bell. To begin with, we discovered when looking into all of this in recent weeks, they were small-scale farmers in places like Lerrachmore and Bowbutts. Then they were farm labourers or forestry workers who lived successively at Heatheryhaugh, Glendye’s Old Lodge and Greendams.

These all feature on Landranger 45. Because it’s ages since we’ve been in Strachan, we’d planned – vainly as it’s turned out – to go there this spring. We hope still to do so sometime. But, for now, Heatheryhaugh, Glendye and Bowbutts will have to remain names on a map.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands