Prior to the dispatch of Britain’s aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth to the Far East the politicians and military chiefs behind the UK’s “tilt to the Indo-Pacific” could usefully visit Stornoway with a view to getting an insight into why restoration of a UK naval presence in the South China Sea may go down badly in Beijing – where politicians know their history.

Looming out of woods on the western side of Stornoway Harbour are the towers and turrets of Lews Castle – a monument to a time when Britain took the lead in subjecting China to national humiliations that have not been forgotten by the rulers of what is now one of the world’s most powerful nations.

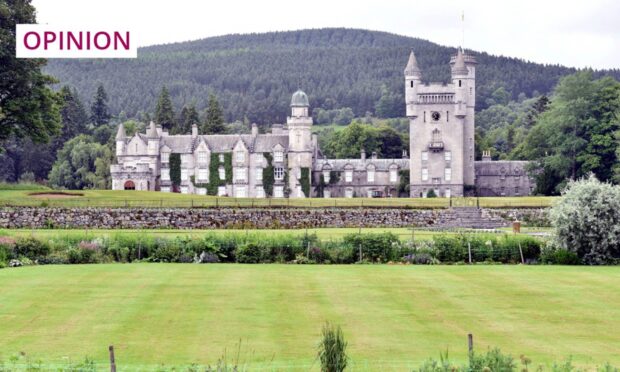

Lews Castle, which took shape in the 1840s, was built to provide Lewis’s then newly-arrived proprietor James Matheson with a stately home matching his status as a self-made man so wealthy his fortune was barely dented by its purchase.

A pointer as to where and how Lewis’s laird made his money is provided by Victorian statesman Benjamin Disraeli’s novel Sybil in which a barely disguised Matheson is portrayed as “a dreadful man, richer than Croesus, one McDrug, fresh from Canton with a million of opium in each pocket”.

James Matheson was one of many early 19th Century Scots to go into business in Britain’s Indian Empire. From there, with Dumfries-born William Jardine, Matheson began to trade extensively with China.

Jardine Matheson, the company the two men set up, is today a Hong Kong registered global conglomerate with more than 400,000 employees and with interests in everything from motor vehicles to luxury hotels by way of property investment, mining and construction.

Back in the 1830s and 1840s, however, the business’s founders owed much of their runaway success, as Benjamin Disraeli more than hinted, to just one commodity. This was opium – grown widely in British-controlled India and shipped into China on vessels owned by Matheson and Jardine.

Jardine and Matheson’s soaring profits rested on their having addicted millions of people to a perniciously debilitating drug.

Soon, it followed, they were in conflict with the Chinese authorities who, in an attempt to curtail the drug business, seized the Scotsmen’s opium stocks and tried to bar their ships from ports such as Canton – which Matheson had made his base.

This, Matheson informed ministers in London, was unwarranted Chinese interference in his and Jardine’s freedom, as British subjects, to trade where and how they liked.

It was time, he insisted, for Britain to bring to heel “a people characterised,” Matheson wrote, “by a marvellous degree of imbecility, avarice, conceit and obstinacy”.

The outcome was the so-called Opium War that broke out in 1839 and ended – thanks to Britain’s overwhelming military superiority – in China being forced to open its ports to British traders and transferring sovereignty over Hong Kong to the UK.

There would be more of this as the 19th Century progressed. Under the terms of a succession of what the Chinese call “unequal treaties”, China was obliged to grant more and more commercial and territorial concessions to western powers.

Sometimes there was protest. Always it was crushed by means such as those that led to British troops looting and destroying Beijing’s Summer Palace in 1860 – a rehearsal for the British army’s pillaging of the Chinese capital some 40 years later.

The world, to be sure, has moved on since those times. And there’s clearly a case to be made for Britain and other democracies responding forcefully to the human rights and other abuses taking place in today’s China.

But now that it’s China, not Britain, that calls the shots in east Asia, it might make sense for our government to be clear about Britain’s past role in the region; a role that, from a Chinese standpoint, was as exploitative as it was reprehensible.

Sending an aircraft carrier to the Far East can readily be seen here as a reasonable rejoinder to China’s repressive actions in Hong Kong and elsewhere.

In Beijing, however, it’s likely to be viewed as a provocative reminder of an era that began with the drug-trading activities of Lewis’s James Matheson and culminated in a bullying Britain treating China as next best thing to a colony.