A decade or so ago, while I was working in London, I got to know a nice woman from the Chinese embassy.

This was useful, as it was around the time that many of us – journalists, academics and politicians – were seeking answers to an ostensibly simple question: what does China want?

She took me for lunch to a fabulous restaurant in Chinatown, where I quizzed her as I guzzled my way through a seemingly endless array of glistening dishes. She was incredibly smart, and dealt easily with my concerns about her country’s growing influence and longer-term ambitions.

I shouldn’t worry, she said: China wanted to be a wholehearted player in the international system of institutions and checks and balances, and a good global citizen.

She responded to my challenges about human rights (offered guiltily, as I slopped down the state-funded crispy duck) with a long lecture about the difficulty of maintaining stability in such an enormous nation. We in the UK couldn’t possibly understand the challenges of governing this vast land mass, with its relatively recent embrace of democracy and capitalism, and its history of coercion and violence. We should be careful about applying our own moral standards to a situation we didn’t properly understand.

In short, they were learning as they went, and the journey was being undertaken with the best of intentions. In any case, she said, a bit of steel entering her voice, the Chinese would take no lectures from the West about hypocrisy, especially when it came to foreign policy. Here she had, I admitted, a point.

Wolf warrior diplomacy

Today, we know quite a bit more about what China wants, but the answers aren’t as straightforward or as reassuring as the friendly diplomat would have had me believe. The story of the country’s emergence as a military and economic superpower is, increasingly, an unhappy one. It seems clear that, if there is ever to be another world war, China will be at its heart and may well be its instigator.

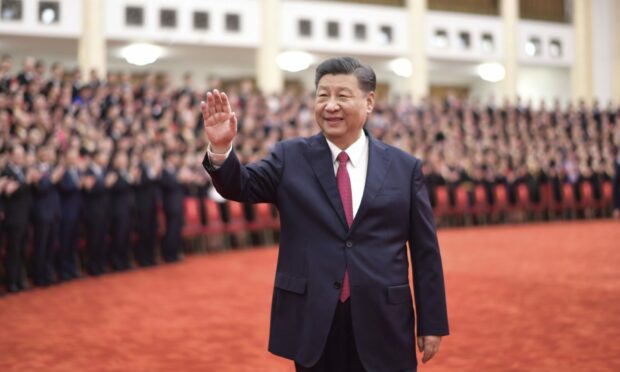

The country is flexing its regional and international muscle, not in any attempt to fit into the global system, but to undermine it. It sees the era of Western dominance as coming to an end, and intends to benefit. Under President Xi Jinping and amid rising domestic nationalist sentiment, it has adopted what is known as “wolf warrior” diplomacy, named after a series of patriotic, Rambo-style Chinese action films. Its officials take a confrontational and belligerent approach to dealing with criticism and challenge from abroad.

China grows more and more assertive, particularly when it comes to contested areas in the South China Sea, where it has reclaimed land and militarised islands it controls. Its hostile approach to Australia was a key motive behind the latter’s recent signing up to the Aukus security pact with the US and the UK. China’s troops regularly clash with Indian forces over the contested border between the two countries. Its relationships with many of the countries in the Asia-Pacific region are torrid.

‘Worsening frictions’

Few will have been heartened by news at the weekend that, though denied by Chinese officials, China has apparently secretly tested a nuclear-capable, manoeuvrable, hypersonic missile that circled the planet before heading towards its target. This capability reportedly took US intelligence by surprise and would potentially allow the missile to avoid American defence systems.

Beijing appears to be turning its back on the international rules-based order and the supranational security and economic architecture

There is also deep concern about the build-up of Beijing’s military forces and its assertive activity near Taiwan, which many fear could be the cause of a future hot war between China and the US.

President Biden’s Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, warned recently about “worsening frictions with China” in the South China Sea and said that any conflict between the two leading powers there “would have serious global consequences for security and for commerce.” Nato’s secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg, suggested there would be a fundamental rethink of the Western alliance’s strategy in order to counter the rising security threat posed by China.

Beijing appears to be turning its back on the international rules-based order and the supranational security and economic architecture. President Xi’s decision to stay away from Glasgow’s COP26 summit next month hardly suggests an enthusiastic embrace of the need to tackle climate change. China’s treatment of its Uyghur population is as notorious as it is abhorrent. The country even refused to allow World Health Organisation scientists to visit Wuhan to explore the origins of the Covid-19 outbreak that wreaked havoc across the planet over the past two years. So much for the good global citizen.

I spoke recently to an American diplomat, and mentioned those earlier, more innocent days of wondering what China wanted from its emergent global profile and power. He frowned. “Well, we know now,” he said, “and it ain’t good.”

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank Reform Scotland