In a courtroom in Atlanta, Georgia last week, the culmination of a real-life drama unfolded.

In voices shaking with grief and anger, the mother, father and sister of a murdered 25-year- old, Ahmaud Arbery, gave filmed testimony. Struggling for composure, his sister, Jasmine, said Ahmaud had curly hair, an athletic build, and “dark skin that glistened in the sunlight like gold”.

Beautiful to her, these were the same characteristics that made three vigilantes claim they thought Ahmaud was “a dangerous criminal” when he was out jogging through their neighbourhood. Sentencing reports about the case appeared in the media, alongside glowing obituaries of the much-loved actor, Sidney Poitier. It was an interesting juxtaposition.

‘Make sure you leave the door open’

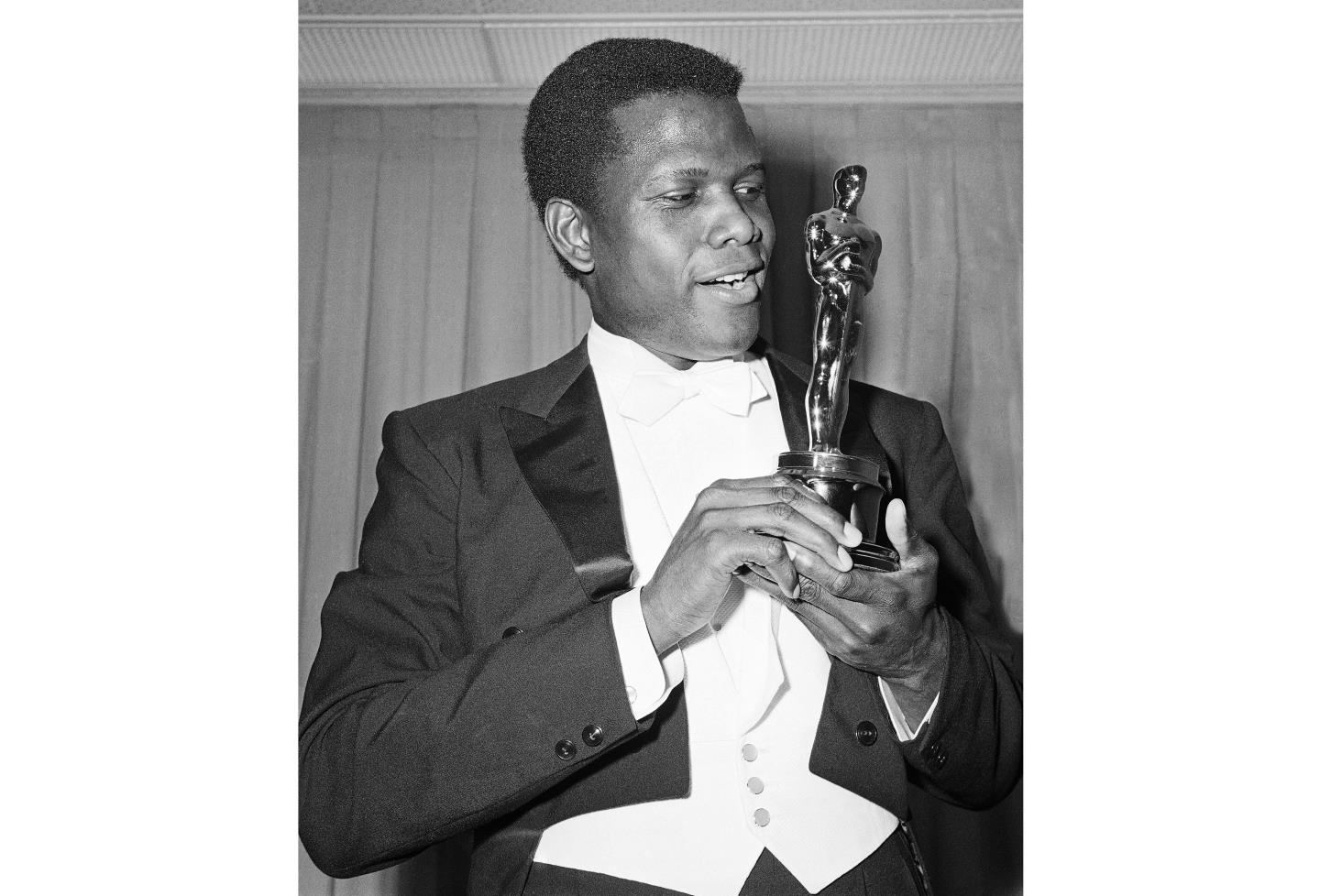

Poitier was the first black person to receive an Oscar, paving the way for actors like Denzel Washington and Will Smith, both of whom paid fulsome tribute to a charismatic man of supreme dignity and elegance. Poitier, they acknowledged, created the conditions in which they could progress.

“When you walk through the doors of opportunity,” Poitier once said, “the one responsibility you have is to make sure you leave the door open.”

Poitier was undoubtedly artistic, but perhaps his greatest creation was himself. He grew up in the Bahamas, so poor that he wore clothes made of flour sacks, coming to America barely able to read and without any acting training.

Yet, poverty did not define him. Poitier was classy, a classiness more potent than any designer label he could later afford.

He became the acceptable black face of white America. Yet, he challenged, too.

The scene where Poitier is slapped by a white cotton plantation owner during the film In the Heat of the Night and slaps back is a shocking but iconic moment that transformed something in the way black people saw themselves in relation to white people. The opportunity doors opened a little wider.

This is not about ‘then’ – this is about ‘now’

The truth, though, is that Poitier – despite having the good looks that could have made him a black Paul Newman – never played a romantic lead role, except one in which his skin colour made him a problem: Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

Despite having the acting talent, he never played The Graduate, or Butch Cassidy, or indeed any part for which he transcended the colour of his skin. He made the films he did because he was black. Just like Ahmaud Arbery died because he was black.

Sidney Poitier transformed our world both on and off the screen. As an Oscar-winning actor and Ambassador, he advanced our dialogue on race and civil rights at a time when we needed it most. My thoughts are with his wife Joanna and his daughters.

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) January 8, 2022

In a tribute, US president Joe Biden said Poitier “held up a mirror to America’s racial attitudes in the 1950s and 60s”. He was certainly a powerful symbol of peaceful resistance, of change and progress in a period where even high profile black artists, like Nat King Cole, experienced resistance when moving into an affluent white area.

But the reason his obituary seemed so poignant sitting next to reports about Arbery was because Biden’s comments were misleading. Poitier held up a mirror to racial attitudes, full stop. This is not about “then”. This is about “now”.

UK Government report ‘repackaged racist tropes and stereotypes into fact’

Every so often, a case like that of George Floyd, or Ahmaud Arbery hits the headlines, and the world takes notice. But it is the silent roll call of less well-known names murdered over the last decade that make this so shocking.

Figures estimate that black men and boys are 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police than white ones

Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old killed by a neighbourhood watch zealot. Timothy Caughman, a 66-year-old sifting through rubbish bins, who was murdered by a white supremacist army veteran. Laquan McDonald, shot and killed by a white police officer. Daniel Hambrick, also killed by a white police officer.

In fact, figures from the National Academy of Sciences in the US estimate that black men and boys are 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police than white ones.

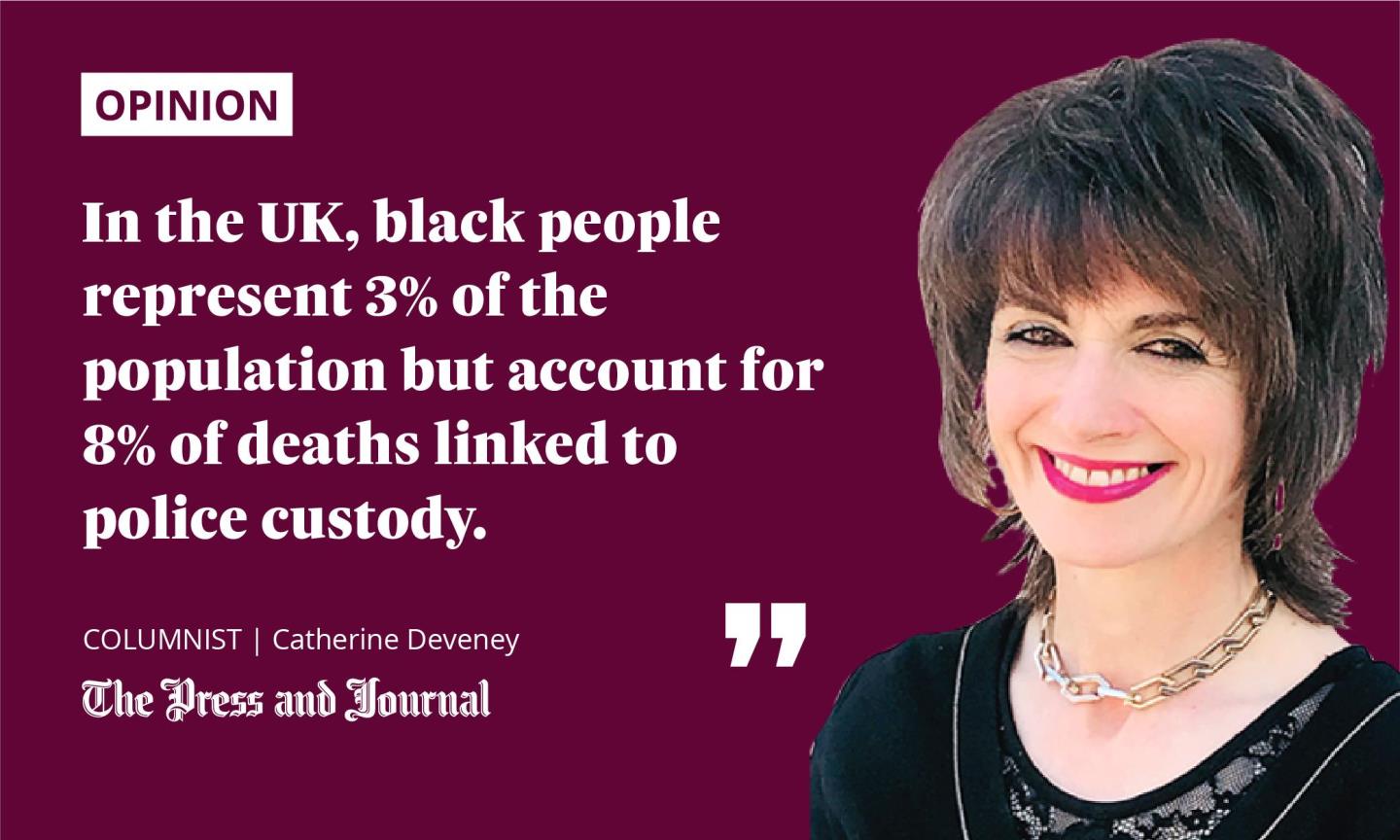

In the UK, black people represent 3% of the population but account for 8% of deaths linked to police custody.

Last year, the UK Government suffered the humiliation of robust UN criticism for backing a report that was commissioned after Black Lives Matter protests.

The report, according to a UN committee, denied the existence of institutional racism and used “dubious claims that rationalised white supremacy”. It was “stunning”, they concluded, to find a report on race that “repackaged racist tropes and stereotypes into fact.”

In the Atlanta courtroom, the judge drew attention to the fact that Ahmaud Arbery was chased for a full five minutes by his attackers. To focus the court’s attention on the fear he must have felt, the judge asked for a minute’s silence in the room.

Sidney Poitier’s death also offers an opportunity for reflective silence – a time to applaud what he achieved for the black community, but also to reflect on how much wider the doors of opportunity need to be wedged open.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter