It was an uncommon, disconcerting feeling, watching the Eurovision vote on Saturday night.

As Sam Ryder’s score piled up, as the dix and douze points poured in, as even France and Germany gave us high rankings, it became hard to avoid an obvious if unlikely conclusion: the UK, that continental problem child and boo-boy, that unrepentant Millwall of European politics, had somehow become popular.

We were never going to win, of course – poor Ukraine had that sewn up long before the first vote was cast. But, undeniably, something alchemical was happening. After years of propping up the board, despite the shock and disruption of Brexit and years of general European disdain for les rosbifs, we were suddenly back in favour. It was like Gripper Stebson being chosen as the school dux, or Will Smith being asked to host next year’s Oscars.

It helped that Ryder himself is one of those hard-to-dislike, man-bunned pixie boys; a wide-eyed child of the universe who seems to float around liking everything and everyone. It helped, too, that his song was a bit of a banger, with a big, booming chorus that fit Ryder’s swooping falsetto.

And, given how political Eurovision is, it helped that Britain has stood most firmly and consistently behind Ukraine in its moment of need, ensuring Vladimir Putin’s victims are bristling with the latest weaponry and providing humanitarian support behind the lines.

We may be many things, but, when it comes to the crunch, our country has repeatedly shown it is a friend to democrats and democracy. In a world of serpentine statecraft and self-protection, actions speak loudly.

No one likes us, we don’t care

Another thing struck me on Saturday – pretty much all the songs were good. I’m not sure this is an entirely welcome development, as the point of Eurovision (for Brits, at least) has always been to laugh at the continentals’ failure to grasp the fundamentals of pop music.

There were too few girls in sci-fi outfits and Scandinavian lunatics in Scream masks and latin crooners of lovelorn dreck. Instead, the Spanish song was a terrific Beyoncé pastiche, Lithuania produced a top quality piece of slinky disco, Sweden squarely hit the pop target, and so on. For once, Britain could have entered any of their songs, and they could have entered ours – a little sign that perhaps we are growing more alike, not less.

This warm bath of unity, of for once being part of a pack, of being liked, lasted until Sunday morning, when the UK Government made it clear it intends to rip up the Northern Ireland protocol and risk a trade war with the EU.

Even as we wiped the sleep from our eyes and took the empty bottles out to the blue bin, we were back in familiar territory – provocative, self-interested, hard-nosed Britain smashing the windows and chucking chairs. No one likes us, we don’t care.

Today I’m visiting Northern Ireland with a clear message: the UK government will play its part to ensure political peace & democracy, but the parties must come together to restore power sharing and tackle cost of living pressures.

My article in @BelTel:https://t.co/SzOIsJ1dvx

— Boris Johnson (@BorisJohnson) May 16, 2022

I wonder, in the end, how this plays with the broader population. Data published by the Financial Times last week showed that attitudes towards immigrants are on an upward, positive trend, even as the numbers arriving on our shores increase. It’s not clear what has caused this, but perhaps the supposed “control” delivered by Brexit has provided voters with some psychological security.

It was telling, too, that Priti Patel’s unconscionable proposal to send refugees to Rwanda sparked horror among many Tory voters and activists.

Another Britain is possible

What do pro-Brexit voters make of how they have been gamed by Boris Johnson over Northern Ireland? His dismissal of all and any warnings about the border situation was typical Johnsonian can-kicking.

It’s not a coincidence that Sinn Féin is now the largest party in Northern Ireland and that unionist politicians are fuming with the prime minister. His slapdash approach to the technicalities and detail of policy decisions has undermined his government from the start, and now threatens to do the same to the integrity of the country.

The sense that the country is run by a privileged coterie with no grasp of or feeling for poverty’s hard truths is now overwhelming

And do Tory voters really think this government is doing the best it can for the poorest parts of our population? Rishi Sunak, who until recently was Johnson’s heir apparent and was held to be a more thoughtful policy-maker, has effectively turned his back on the needy at a time when the cost of living is soaring, as food, fuel and heating bills spiral out of control.

Things are going to get worse, too. But children and families have been abandoned to poverty, while the government is refusing to use the most immediate mechanism at its disposal – Universal Credit – to boost their incomes. The sense that the country is run by a privileged coterie with no grasp of or feeling for poverty’s hard truths is now overwhelming.

There have been so many years of this – of neurotic Tory infighting, of shifting ever further right to appease an unappeasable fringe, of a belief in British exceptionalism which only serves to expose our wonky, duct-taped wiring – that it has all started to feel normal.

And, so, Saturday night was a wee window into another Britain, a Britain with a man bun and a big smile, a big heart and a sweet voice. I must confess, a part of me thought: can’t we be this instead?

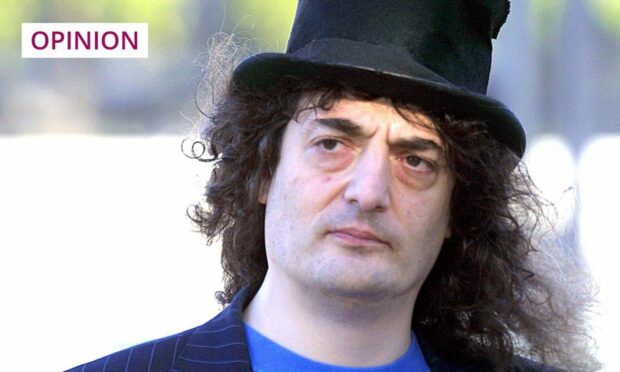

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation