Fed up with Christmas? If you are it’s hardly surprising, as it seems the celebrations have been going on since the summer, and appear to advance a few days annually.

We now have almost two months of constant television adverts aimed mainly at children, who in turn will pester their parents for this year’s “must-have” gifts.

The shops are packed, and if I hear Wham’s “Last Christmas” once more I’ll scream. On top of that, large vans delivering online orders are clogging the streets of our cities, towns and villages.

It’s all a far cry from the true message of Christmas. Not, of course, that the version of the Christmas story as told in our churches every year should be taken without a large pinch of salt. Of the four Gospels included in the authorised version of the Bible, only two – Luke and Matthew – even mention the birth of Jesus. Both were written some 40 or 50 years after the crucifixion and are probably from second or third-hand sources.

And even these two Gospel accounts don’t agree with each other. Only Matthew mentions the slaughter of the innocents and the three wise men, while the three shepherds are described only in Luke. After the birth, one account has the family fleeing to Egypt, while the other sees them heading peacefully to Jerusalem.

And nowhere in any of the Gospels does it claim that Jesus was born in a stable, only that he was laid in a manger, a trough for feeding animals. In those days, animals would have shared houses with families, just as they did in the Highlands up to the 19th century.

However, even leaving aside the discrepancies over the Biblical account of the events, the historic celebration of Christmas appears to have little to do with Christianity. Even the date on which we celebrate the event, December 25, was probably simply hijacked from an earlier pagan winter solstice event. Indeed, the continued use of mistletoe reflects the fact that in pre-Christian days it was thought to be a magic plant with special powers, since it appeared to have no roots.

The use of holly at this time of year also dates back to pagan times, and Druids are said have worn holly crowns. Later this was absorbed into the Christian tradition with the holly leaves said to represent the crown of thorns, and the red berries the blood of Jesus.

Over the centuries, more and more Christmas “traditions” have been invented and added to how we accept the celebrations today. The yule log is thought to have Nordic pagan origins. The Christmas tree too is believed to be pagan – it was the custom to bring evergreen branches inside in winter to symbolise the continuity of life, even in the darkest months of winter.

This evolved in 16th century Germany into the Christmas tree as we know it today, and its popularity in Britain dates from Victorian times, when Prince Albert introduced the tradition to Britain.

And what about the jolly figure of Santa Claus? He’s based on St Nicholas, an early Christian bishop based in what is now modern-day Turkey who, noted for his secret gift-giving, became associated with Christmas gifts. It’s often said that the fat, white-bearded, red-dressed Santa was an invention of Coca Cola.

However, the figure was first portrayed in this way by the cartoonist and illustrator Thomas Nast, in the American magazine Harper’s Weekly, in 1862. Coca Cola began using the figure in their advertisements in the 1920s, and by the 1930s, the red-dressed jolly Santa figure was famous throughout the world

Around that time, the real commercialism of Christmas began to kick in. And even in my own lifetime, the expectation which today’s youngsters have on Christmas morning is far beyond anything previous generations have experienced.

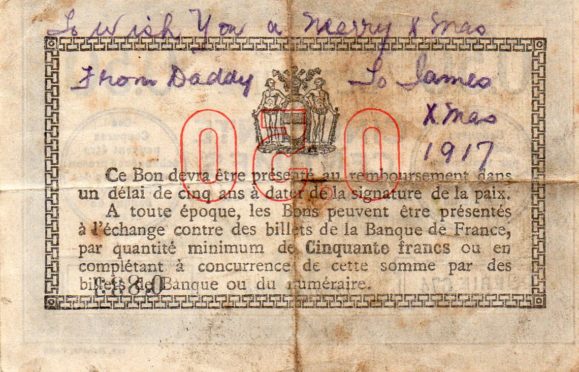

But before anyone blasts me for my “bah humbug” attitude, I should point out that one of my treasured possessions is a 50 centimes banknote issued by the Chambre de Commerce de Bethune, in Northern France, in April 17, 1916. It was sent to my four-year-old father for Christmas 1917, by his own father, who was serving in the First World War trenches.

On the back of the note, my grandfather has written, “To Wish You a Merry Xmas, From Daddy To James, Xmas 1917”. Fifty centimes was probably worth just a few pence, even back then. But it was the only Christmas present my father received that year, and he kept that banknote all his life. I now have it and in due course will pass it on to my own children or grandchildren.

This worthless tattered wee piece of paper is more valuable to me than all the expensive electronic games or high-tech wizardry on offer in our shops today.

And it is far more symbolic of the true meaning of Christmas.