“Social class” has become a phantom phrase in Britain; a concept that lurks around like a bad smell but nobody cares to mention in case everyone else thinks the stench comes from them.

An article in this month’s Psychologist magazine suggests the lack of attention to class is a product of us all being too busy perpetuating the myth that we live in a meritocracy.

It took just one brief YouTube video this week to belie that particular urban myth. Cabinet minister Michael Gove – who has admitted in the past to a snort or two of cocaine – features in a video that cleverly splices him dancing erratically in an Aberdeen nightclub, with scummy heroin addict, Renton, from 1996 film Trainspotting moving onto the dancefloor, “fuelled by alcohol and amphetamines”.

What’s the difference between a ned and a Tory minister?

The clip of stuffed shirt Gove struttin’ his stuff has amused many on social media but the serious side is this: attitudes to alcohol, drugs and addiction are influenced by attitudes to class.

Society’s responses to mind-altering substances vary, depending on who’s consuming them: a tipsy middle class man in a suit, whose inhibitions are sufficiently loosened to do dad dancing without a blush, is seen rather differently from the T-shirt clad, unemployed Renton.

The unspoken question the video challenges with is this: what’s the difference between a ned and a Tory minister? Now there’s a question I’ve been trying to find an answer to for years.

The answer – in no particular order – is probably money, circumstance, opportunity and privilege. It wasn’t just Gove’s antics that brought that home forcefully this week.

Literature has a Mr Pledge effect on addiction

In the past, I have admired Peter Krykant, a former heroin addict who converted a bus in Glasgow to offer a supervised facility for drug addicts. As a society with drug deaths now three times higher than a decade ago, we should have been grateful; former addicts have so much to give others when they get clean. If he’d worn a white coat, we’d probably have given him an OBE for his work.

Without a political or literary voice, Krykant was simply another failed junkie who wasn’t really heard by the establishment

Instead, forced by the establishment to operate as a maverick, Krykant was threatened with prosecution and eventually buckled under the weight of trauma he was dealing with. After 11 years clean, he relapsed. What was really disturbing was that when he tried to get help in Scotland, he found it impossible. He went to England.

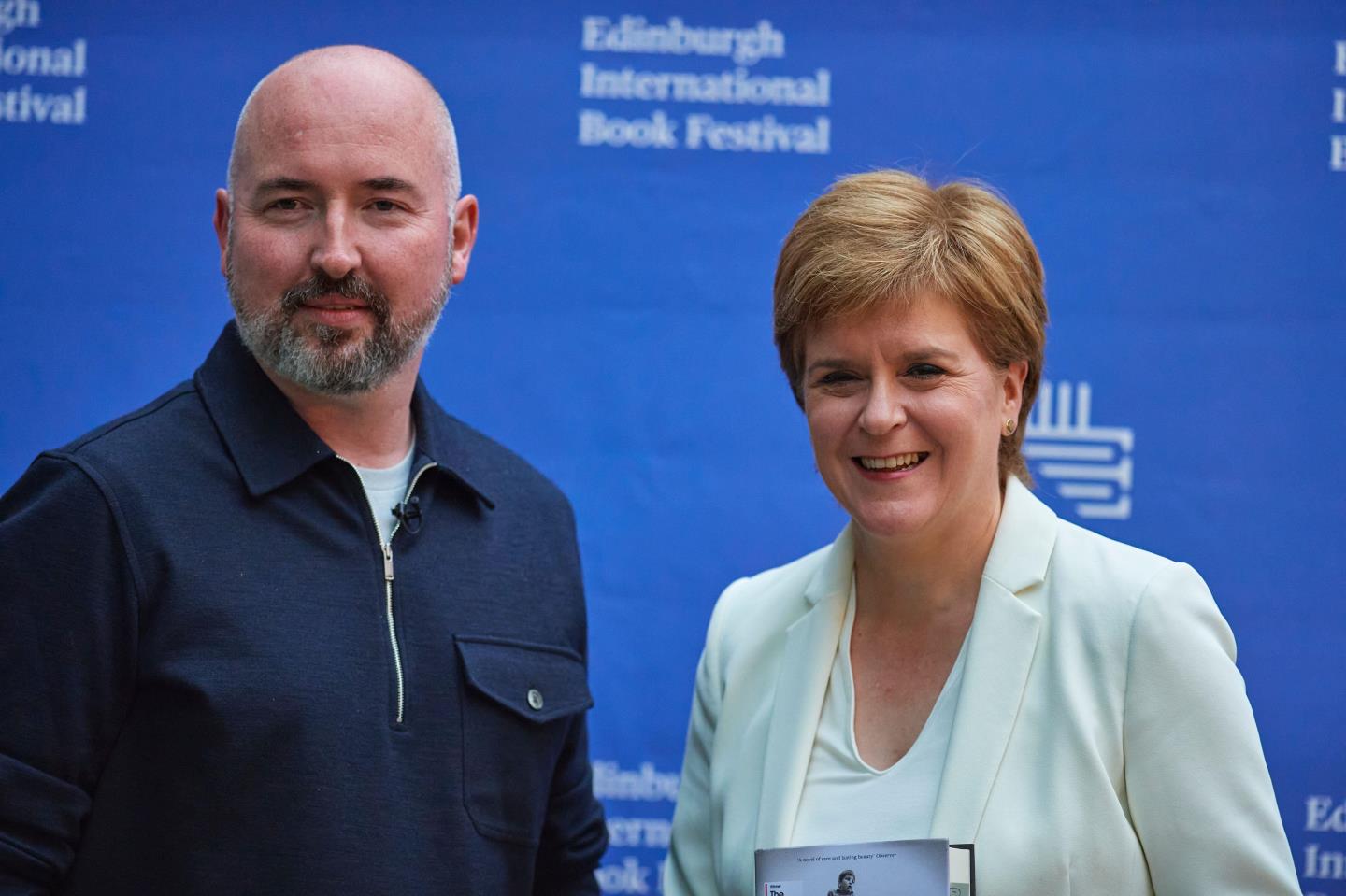

Krykant’s story came in the same week that First Minister Nicola Sturgeon interviewed author Douglas Stuart about his Booker-winning novel, Shuggie Bain, at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. Stuart explained the connections between the novel and his working class Glasgow background, especially his mother’s alcoholism.

Class is about education as well as money. However dark the story, literature has a Mr Pledge effect on addiction, polishing it up to be a rough diamond of creativity. Without a political or literary voice, Krykant was simply another failed junkie who wasn’t really heard by the establishment.

“We have so much to do…” Sturgeon told Stuart, “to help people suffering from addiction.” Yet, the Scottish Government has spent record levels of money on drug addiction, with a further £4 million announced earlier this year to ensure addicts got help on the day they asked for it, no matter where they lived. What’s going wrong?

Perhaps the fact that we have little empathy for causes of addiction that are connected to socio-economic factors we no longer want to recognise. And also the fact that the NHS is a bureaucratic mess, whose response to addiction – despite government policy – is often: “Name? Postcode? Sign here. Wait there.”

Too much of an addict for NHS help

One benzodiazepine addict I know of – call him Jamie – became hooked after being prescribed Valium by his GP to deal with anxiety. On street benzodiazepines, his voice was slurred and he sounded drunk, or stupid, or both. He had no job and lived in a scheme. His addictions nurse refused to answer his calls half the time. She didn’t know – or care – that he used to write poetry.

Desperate for help, Jamie was refused detox and rehab consistently because, he was told, he had to cut his intake in half before he would be considered. Yes, you read that right. He was too much of an addict for the NHS to help his addiction.

Jamie could be Renton in that Gove video. The tendency to judge by appearance, to judge people according to their outer layer rather than their inner one, was always the drawback of talking openly about “class”. But to pretend that it no longer exists, that we somehow all suddenly got equal, is one big societal hallucination too far.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter