Reacting to last week’s finding that nearly 300 village and small town post offices have been lost in Scotland’s north and north-east over the last 20 years, Caithness, Sutherland and Ross MSP Maree Todd said such places have long been “at the heart of rural life”.

I’m with Ms Todd on the importance of post offices, not least because I was born and grew up in one – a claim that isn’t quite the stretch you might think.

From the 1940s until the 1980s, the post office in Duror, a small community near Ballachulish, was run by my late mother and operated from what had formerly been a ground floor bedroom in our family home.

This post office, when I first got to know it in the early 1950s, contained lots to interest a little boy.

Delicately-balanced scales on which letters could be weighed with the help of diminutive brass weights. Much larger scales for parcels – with, alongside, a set of lead-filled weights that ranged from one ounce to five pounds.

A date stamp and its ink-soaked pad. A big black book containing sheet after sheet of stamps of differing values. A drawer with neatly filed postal orders, wireless licences, dog licences and other items.

A neighbouring drawer from which there could be extracted a seemingly inexhaustible supply of ha’pennies, pennies, threepenny bits, sixpences, shillings, florins, half crowns, 10 shilling notes, pound notes.

Mailbags thought to be put together by prisoners

And, in a corner, out of sight behind the counter, a pile of musty-smelling mailbags – all the more fascinating because of the thought, correct or not, that mailbags were put together in Britain’s jails by teams of prisoners.

Each afternoon at about three, the letter box that had taken the place of one of the panes in our post office’s window was opened and its contents added to such letters and parcels as had already been placed in the day’s outgoing mailbag.

The bag was then secured. First its neck was folded in the regulation manner – prior to having wrapped around it a generous measure of officially supplied string.

Once this had been knotted tightly and any surplus cut away, a candle was lit. Next, a stick of shiny brown wax was held over the candle flame in such a way as to ensure that melting wax dripped over the newly tied knot at the mailbag’s neck.

When enough wax had accumulated, a dampened brass implement was firmly applied to it. This left in the cooling wax a seal bearing a royal crest and an inscription. “Duror PO”, it read.

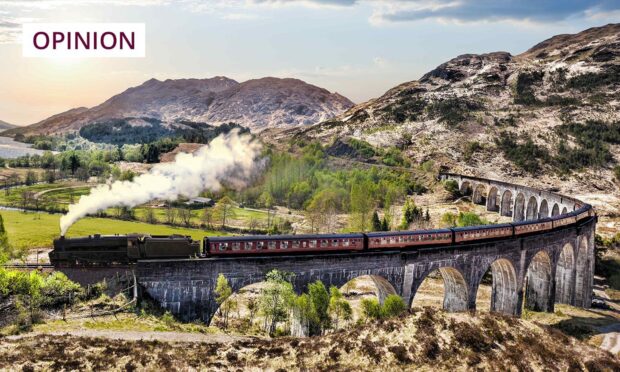

Once all this had been accomplished, the bag was taken by bike to Duror station where, as was dinned into me when I was old enough to be entrusted with this task, the mails were to be handed over to no one other than the British Railways guard in charge of the train that would take them on to Oban and points south.

As shown by her insistence on these formally laid down procedures, post office responsibilities were taken seriously by my mother who – though paid just £2 a week to begin with – was part of a nationwide organisation which, unlike today’s wholly privatised postal service, was a government department presided over by a cabinet minister.

Something of what this entailed is reflected in my mother being subject to the Official Secrets Act. Her post office was the Duror people’s principal point of contact with the UK state.

Here folk came weekly with booklets containing the detachable slips of paper they exchanged for family allowance or pension payments. Here mothers called to collect the National Dried Milk, concentrated orange juice and cod liver oil supplied free of charge to households containing young children.

And here in the bygoing, as in the nearby shop where Duror’s post office migrated on my mother’s retirement, all sorts of news and views could be exchanged.

Its shop has gone from Duror. So has the six-days-a-week post office I knew 60 and more years back.

Does this matter? Postal orders are as obsolete as dog licences. Surely it’s more efficient – more economical – to send emails instead of letters; to have your old age pension paid automatically into a bank account you can access instantly from home? And aren’t we better off without a nanny state supplying parents and their kids with orange juice?

Maybe. But I think there’s more than nostalgia for the 1950s wrapped up in my conviction that, with the closure of our rural post offices, something of national, as well as local, consequence has been destroyed.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands

Read more by Jim Hunter