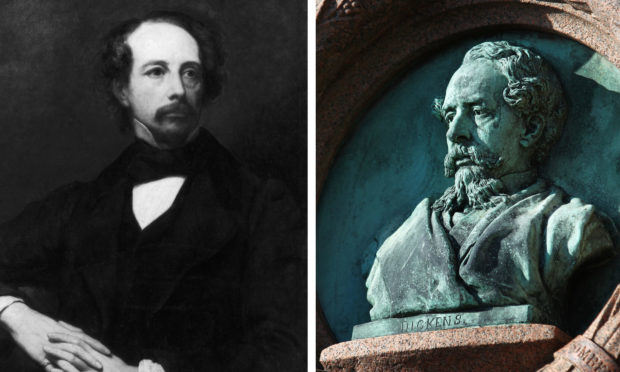

He is one of the world’s most famous authors; a man whose creations from Mr Micawber to Ebenezer Scrooge and Oliver Twist to Little Nell have become part and parcel of English literature.

And, although Charles Dickens died 150 years ago – at the age of only 58 – he packed so much into his peripatetic life, from writing a rich canon of novels, to penning political sketches and editing anthologies, embarking on global speaking tours and encouraging others to follow in his footsteps, that his place in the pantheon is assured.

Rectorship offer

Even his surname has entered the dictionary – as in “What the Dickens!” – while he has become renowned among crossword solvers as the answer to the clue “Famous Victorian creator of children’s cakes” (7,7).

But it might be less well known that Dickens was once offered the opportunity to become the rector of Marischal College and he subsequently published a story by one of his contemporaries about a murder at the majestic Aberdeen site.

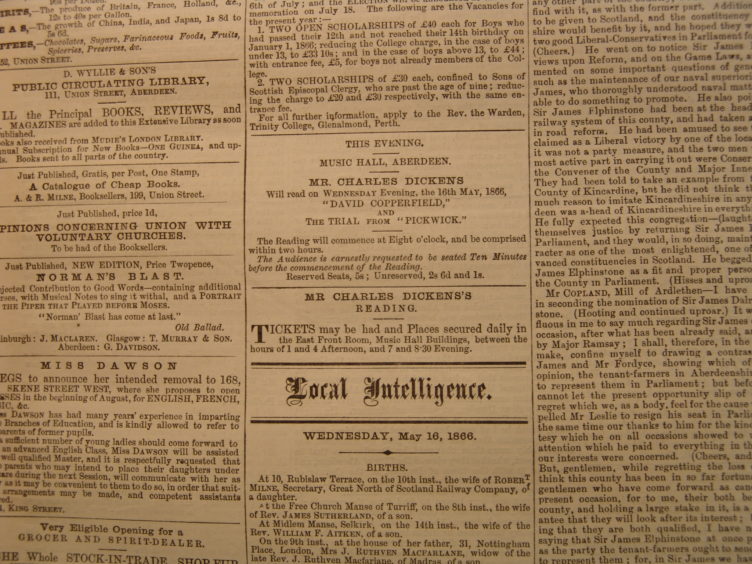

Then, there were the two occasions when this iconic figure travelled to the Granite City to parade his talents for acting and mimicry while reading extracts from such famous novels as David Copperfield and Dombey and Son.

In 1849, when the author was at the height of his powers, he was invited by a significant number of students to stand for the role of rector.

Students had great expectations for Dickens

James Donaldson, a third-year undergraduate who later became Professor of Humanity at Aberdeen University from 1881-86 and the vice-chancellor of St Andrews University in 1890 wrote to the great man, urging him to accept the nomination.

This was – and still is – a post on the university’s governing body which is filled after an often boisterous student election.

The alumni also invited Hugh Miller, the Scottish geologist and religious activist, to throw his hat in the ring.

But both men declined the proposal and Dickens told Donaldson in a letter: “I beg to assure you that I am very sensible of the feeling which has induced you to propose me as a candidate for the Lord Rectorship of your college.

“But in reply to your note, I am constrained to say, without any reservation, that I do not aspire to the high honour and I must entreat you to withdraw my name.”

Aberdeen University Dickens expert, Dr Paul Schlicke, has investigated every facet of the writer’s life and has no doubt as to why he rejected the invitation.

Determined to oppose

He said: “The reason is clear – he was being asked to stand against the incumbent, John Thomson Gordon, whom the students were ‘determined to oppose’.

“However, Gordon, formerly Sheriff of Aberdeen and then of Edinburgh, was one of Dickens’ closest Scottish friends.

“They had met at a banquet in 1841, where Gordon gave the (Immortal) Memory of Burns, a speech which Dickens considered ‘masterly’.

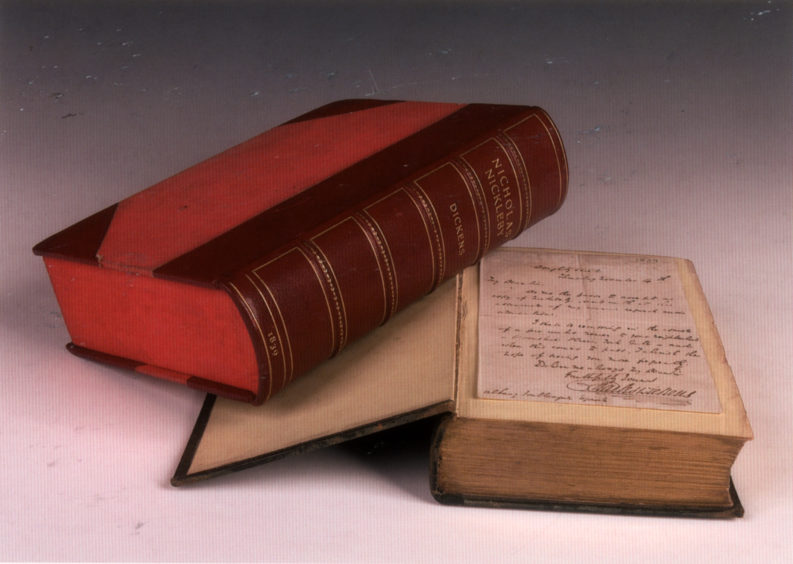

“Gordon hosted a dinner in Edinburgh for Dickens’ theatrical company in 1848, and, in the same year, Dickens presented him with an inscribed copy of The Haunted Man.

“They had entertained one another, both in London and Edinburgh, and remained in contact until Gordon’s death in 1865. It’s not surprising he refused to oppose his friend.”

Murder, mayhem and hard times for poor Downie at Marischal College

Although Dickens travelled north of the border on a regular basis, there are few mentions of the country in his own novels and myriad other literary works.

Yet there were many articles and fictional creations about the Scots in the journals he edited, including a sensational story set in Aberdeen, which appeared in Household Words in 1852 under the macabre title: “Who Murdered Downie”.

The offering highlighted Dickens’ penchant for crime writing – he also championed the famous Wilkie Collins story The Moonstone – and although the tale was published anonymously, the journal’s office book revealed it was one of six pieces written by James Knox, Scottish editor of the Daily News, which Dickens edited briefly in 1846.

Dr Schlicke said: “The article recounts the mock trial and execution of Richard Downie, Sacrist of Marischal College in the late 18th century, by a group of undergraduates who were seeking revenge for Downie’s officiousness in reporting student misdemeanours to the university authorities.

“Having lured the poor man to a darkened room, the masked students enacted a ceremony in which they convicted him of ‘conspiring against their just liberty and immunities’ and made him kneel before a block to be beheaded.

“However the prank went horribly wrong when Downie, struck on the neck by a wet towel, died of fright. The students vowed one another to silence and the truth emerged only in the deathbed confession years later of one of the students.”

It sounds like an early version of the script for a horror film such as I Know What You Did Last Summer, but Dr Schlicke isn’t surprised that the story appealed to Dickens.

He added: “The version in his magazine is an entertaining morsel of Gothic titillation, of the sort known today as an urban legend: a sensational fictitious event, presented with abundant local detail as being authentic historical fact.

”Characteristically of Dickens, the tale which he printed casts a romantic aura over the location described.

”The granite city of Aberdeen is shown by him to hold mysterious secrets.”

Author’s visits to Aberdeen were the best of times, the worst of times

His first visit, on October 4 1858 came at a difficult time in his personal life. A few months earlier, his 22-year marriage had come to an acrimonious end after he fell in love with a young actress, Ellen Ternan, and the smitten writer had attempted to explain his actions by writing in his journal, Household Words.

The press was unimpressed by the author’s defence and Dickens’ arrival in Aberdeen led to him becoming the subject of vociferous criticism from local readers.

One correspondent took issue with the author’s outspoken backing for Sunday amusements. Another writer, signing himself “One of the church-goers of Aberdeen”, suggested that anybody who attended Dickens’ readings at the Music Hall should donate a sum equal to the price of their tickets to the Sabbath societies of London.

But, as Dr Schlicke added: “In the event, the visit went well. There were adulatory reviews in the Free Press and the Aberdeen Herald.

“The Aberdeen Journal’s man sniffed that a visit of less than 24 hours was ‘a short time to spend in our fair city’, but the writer soon changed his mind.

“He wrote: ‘We had not long listened to him when we felt that the creations of his fancy gathered tenfold vigour from his representation and that he….had the power of giving a more visible and determinate embodiment to his creations’.”

Or, to cut to the chase, he could bring a tear to a glass eye.

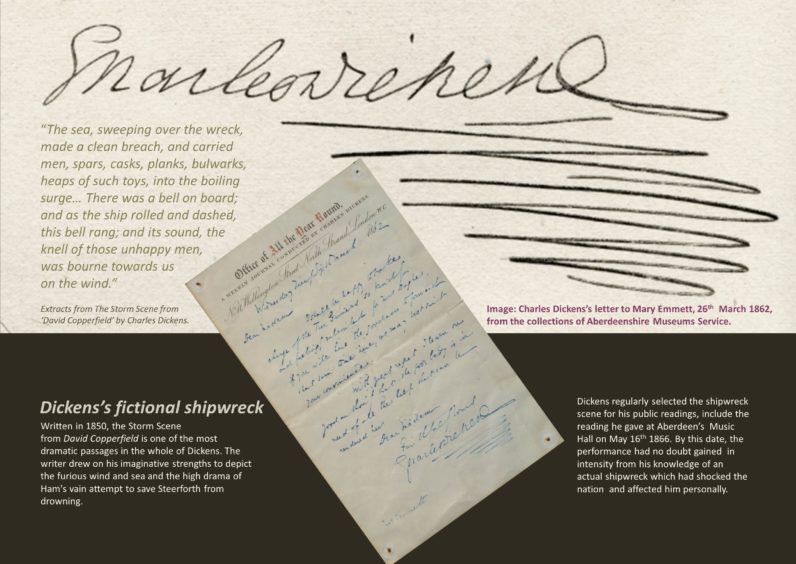

A second and final visit came in 1866, when the writer was 54 and in poor health, suffering from a bad cold and pain in his eye and hand. He travelled to Scotland by train with his tour manager, George Dolby, this time to deliver just a single reading.

The gruelling two-hour performance included a dramatic rendition of the storm scene from one of his most cherished novels, David Copperfield, which was followed by the comedic trial scene in The Pickwick Papers. And, despite his afflictions, he rallied himself sufficiently during the event to regale the crowd with a sailor’s hornpipe.

Dickens always loved performing and was a talented mimic, giving an impressive range of voices to his popular characters and bringing them to life for his audience.

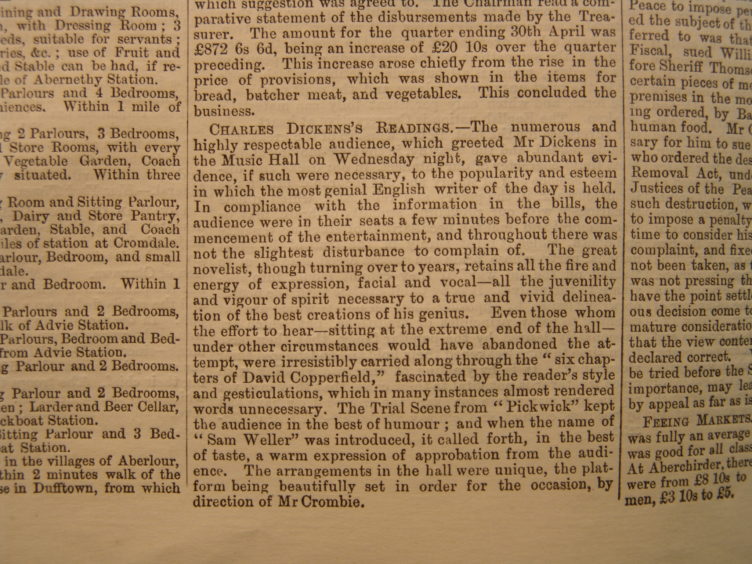

Contrary to Dolby’s assessment that this had been “the least-well received of any of Dickens’s readings”, press reviews were gushing in their praise of the celebrity writer and the Aberdeen Journal was enthusiastic about acclaiming his bravura display.

Its report read: “The audience gave abundant evidence, if any such were necessary, to the popularity and esteem in which the most genial English writer of his day is held.

“The great novelist, though turning over in years (ageing), retains all the fire and energy of expression, facial and vocal, and all the juvenility and vigour of spirit which is necessary to provide a true and vivid depiction of the best creations of his genius.”

He went through his own hard times before his death on June 8 1870. But Dickens remains one of the enduring giants in literature.