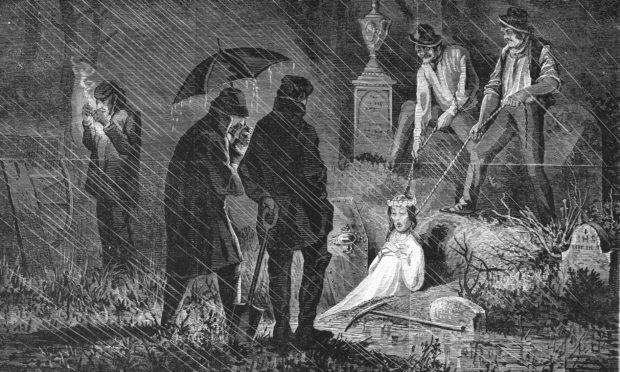

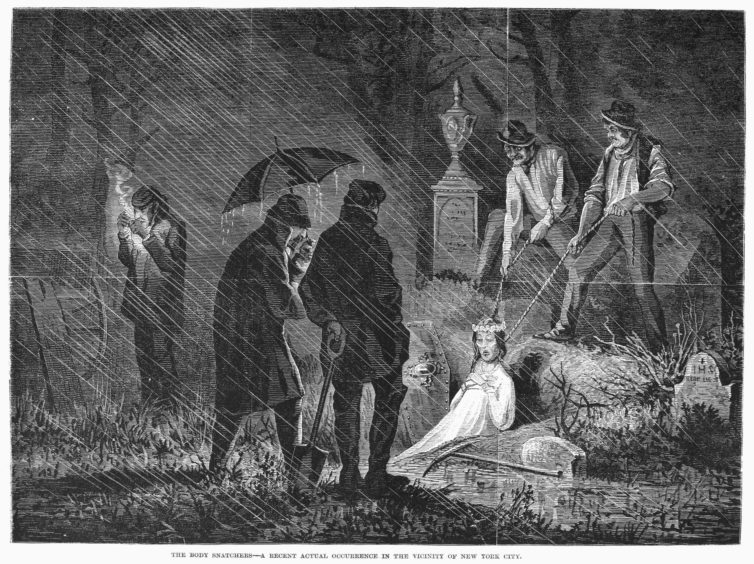

It was a time when the people of Aberdeen lived in terror of bodysnatchers – the grave robbers who would dig up your recently deceased loved ones to be dissected at the hands of anatomists and medical students.

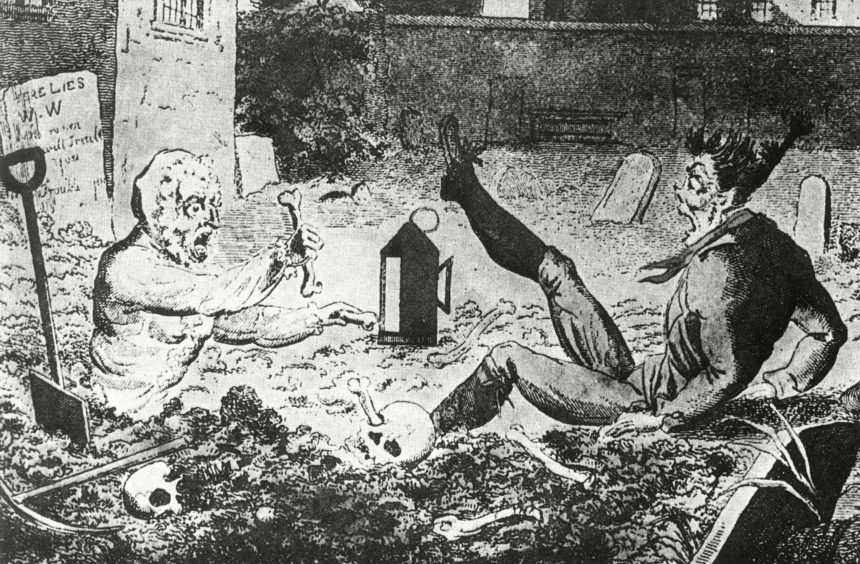

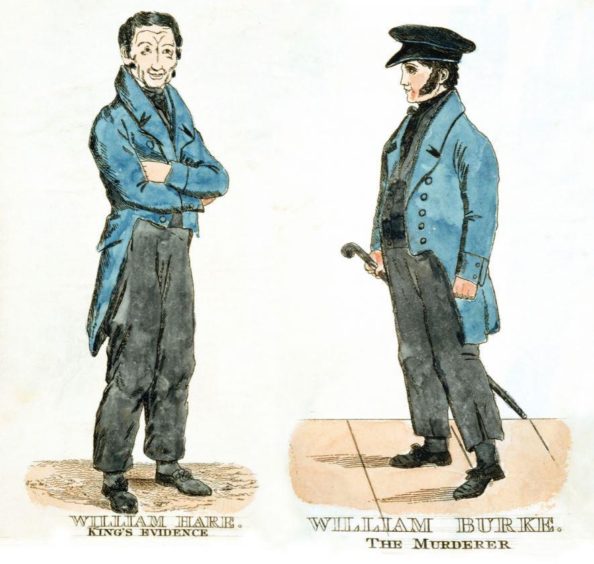

Added in to this febrile atmosphere, 190 years ago, was the national revulsion at Burke and Hare, convicted of murdering 16 people in Edinburgh and selling their corpses to the resurrection men.

Not, you might think, the best time to be making plans to open your own anatomy room in the Granite City – a place where students were already being chased and attacked as “Burkers”.

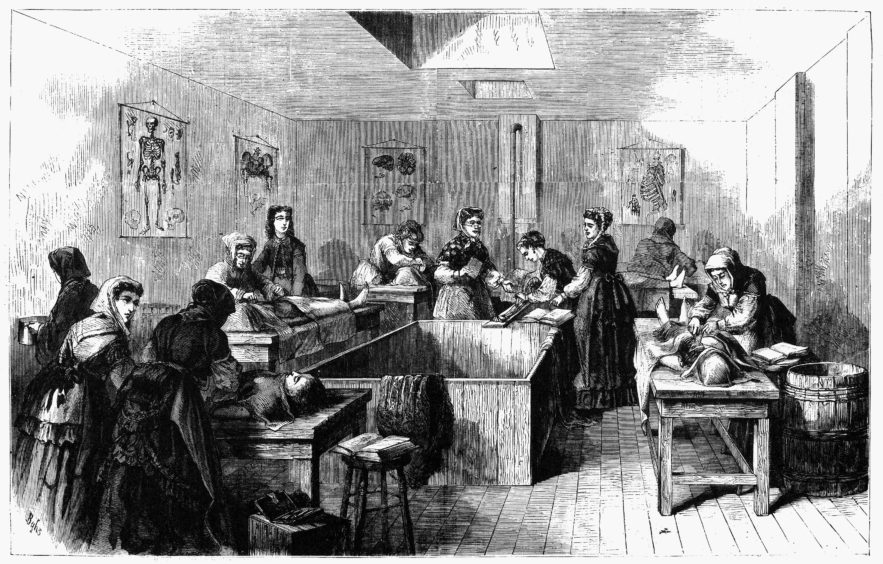

But, undaunted, famed doctor, Dr Andrew Moir pressed ahead with his vision to teach and show the workings of the human body, opening his Anatomical Theatre in 1831 on St Andrew’s Street, an imposing building with blacked-out windows, where the Sandman Signature Hotel now stands.

A month later, a furious baying mob set it ablaze, wrecked it and almost succeeded in demolishing it in a riot involving possibly as many as 20,000 angry citizens, enraged after a dog dug up human bones behind the grim building.

Dr Moir and his students fled for their lives and the medic was forced to flee the city for a while, reviled by the citizens of Aberdeen.

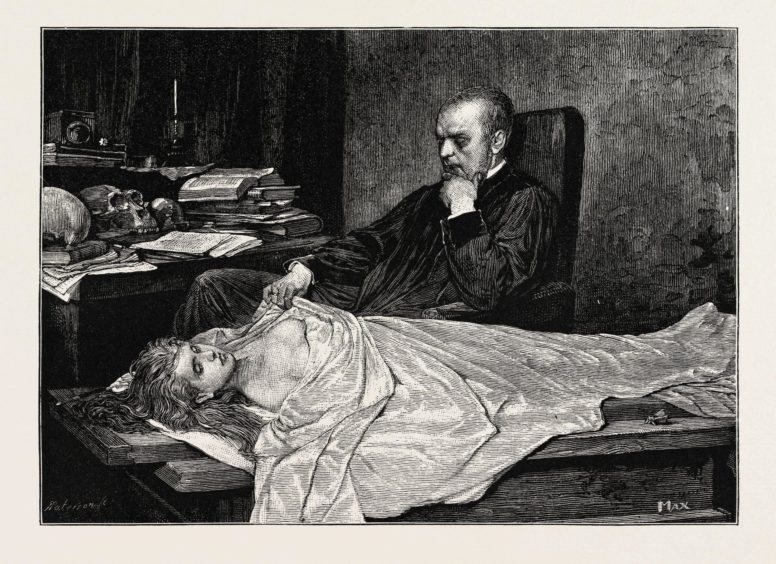

But the medic doesn’t deserve his reputation as a grim bodysnatcher, according to local historian, Dr Fiona-Jane Brown.

In fact, he was a caring professional who returned to Aberdeen and helped lay the foundations of the city’s renowned medical schools and reputation for cutting-edge research. His early death was not at the hands of an angry mob, but as a result of catching typhoid as he treated the poor.

And she believes it is time to focus on that laudable legacy and not the tarnish left by the bodysnatcher riots which rocked the city.

It was an event which made headlines at the time in lurid newspaper reports across the country.

Dr Brown said: “Some local children were playing with a stray dog and the dog came to them and had a bone in its mouth and someone recognised it as an arm bone. Local apprentices, older boys, saw the dog had come from around the back of the anatomy school.

“They charged into the building and started attacking the students. Dr Moir cleared the place and told everyone else to run.”

A newspaper report from the time talks of 20 to 30 people gathering after the boys raised the alarm and dug further to find fragments of a human body.

“The crowd then raised a shout of horror and made for the door of the theatre. They found Mr Moir himself in the place, assaulted him and turned him out,” said the story.

Part of the crowd which had gathered chased the doctor to his home and into a room where he escaped by jumping out of a window and fleeing.

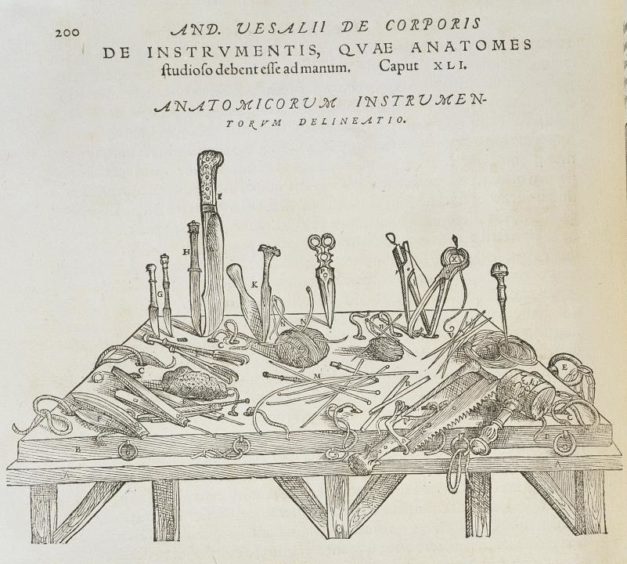

One newspaper report said the crowd had rushed into the anatomy room building and found three bodies lying on boards and the “paraphernalia” of the dissection procedures lying around. Officers had arrived from the Town House and directed the bodies be taken out.

“When the mangled corpses were brought to the open air and lain on the ground, the loud yells of the crowd and their cries for revenge baffle description. ‘Burn the house down – down with the burking shop’ was now the cry,” said the report.

The angry mob gathered up wood, including fir and tar-barrel staves and started a fire in the building.

The news report said: “The crowd then commenced undermining the back wall with large planks, one of which they used as a lever and the other as a battering ram. So quickly did they do their work within five minutes the whole of the back wall fell down with a tremendous crash.”

With the building ablaze and the back wall demolished, the outraged citizens set to work on the front of the building.

Dr Brown said: “Various reports say either 10,000 or 20,000 people end up gathering around it. It’s by force of numbers they push down the back wall. The whole place ends up collapsing.”

By this time the city’s Provost James Hadden arrived on the scene.

Dr Brown said: “He reads the Riot Act, the first incident of it being read in Aberdeen. He has police all around him and soldiers further up on Schoolhill. But he had said: ‘Tell them not to come near we don’t want a situation’.

“But the folk just laugh at him and carry on wrecking the building. The only reason that nothing worse happened was because it started raining and folk finally dispersed after about four hours of mayhem.”

Rain or not, the mob had done their work. “About eight o’clock, the Anatomical Theatre was completely destroyed, literally not one stone being left upon another”.

Some of the crowd roamed the town pursuing medical students – all of whom escaped – but by 10pm the city was quiet again.

The ferocity of the riot might seem surprising to modern eyes, but the feelings against bodysnatchers and anatomists were running high across the country, said Dr Brown, and the dog’s grisly discovery of bones was merely a trigger for that rage.

“Really, it was a fall-out from the Burke and Hare case in Edinburgh. From 1829 onwards, folk started getting really scared and it kind of created a mass hysteria,” she said.

“Marischal College and the medical school was then a target. All the youngsters would throw things at students. There was an incident involving two law students. One of them talked about running down the Vennel, and getting chased and being ‘pelted with dead hens by the roughs and called Burkers’.”

The fear wasn’t restricted to the city, where medical students would go out and dig up bodies. In the shire there were professional resurrectionists – a practise that gave rise to the urban legend of “Twice-buried Mary”.

Dr Brown said: “It was supposed to be a lady called Mary Elphinstone who was actually in a coma, but buried alive. She was married to James Elphinstone of Logie and actually buried in her wedding dress with a diamond ring on her finger. These would-be grave robbers dug her up and were trying to cut the ring off her finger and that’s what woke her up.”

So widespread was the practice of grave-robbing that extraordinary measures were taken to keep the bodies of loved ones out of the hands of the resurrection men. That included the building of watch-houses and towers to guard over freshly-dug graves, with examples still standing at Nether Kirkyard at St Cyrus, Old Dyce graveyard (which has gun loops) and Banchory Ternan graveyard.

Dr Brown said: “The bell tower at the old Kirkburn cemetery in Peterhead was used as a watchtower because it is about 50 or 60 feet high. Cluny Kirkyard still has some intact mort cages, the iron cages they put over graves. Only the rich could afford mausoleums so a compromise was to get a blacksmith to build you a mort cage which was dug into the ground.

“Another medical historian friend of mine discovered this ‘cemetery gun’. It was like a rifle with a trip wire that would fire off rounds if it was tripped.”

Another method was the mort-house, like the one still standing in Udny Green kirkyard.

Dr Brown said: “It was finished in 1832, the year after Andrew Moir’s riot and the year of the Anatomy Act which regulated the supply of bodies to medical schools. It was barely used at all, but is a good example. What they would do is put coffins on a rotating table. By the time it had rotated six times the body would be decomposed enough the medical students wouldn’t want it.”

There was sympathy in high places for the antipathy towards the anatomists, too. Those arrested after the Aberdeen riot were dealt with remarkably leniently for the time.

Dr Brown said: “There were only three men arrested; that was all they could catch. You have to think here, that fire-raising was an executable offence and they could have been hanged. They pleaded they just got carried away and got off with it. Well, they ended up in the Tolbooth being fined, but they didn’t get hanged.

“Dr Moir only got minimal damages and the absolute wrath of the Aberdeen Journal’s editor, basically saying what do you expect is going to happen if you go and open an anatomy school after what’s happening in Edinburgh. There was no sympathy for him whatsoever.”

But medical professors and students were forced to extreme measures to continue their research and to help advance the science, given the lack of corpses to dissect, study and understand.

“There was very little other way for them to get bodies,” said Dr Brown, saying there had been a long-standing aversion to dissection both within the Kirk and general public.

“The only legal way medical students could acquire bodies was from the gallows. But there were so few. From 1800 to 1857, the last public hanging in Aberdeen, there was only about 20 executions.

“There was such a shortage for learning anatomy they decided to start (grave robbing) inspired by the resurrectionist practices in London where the King’s Surgeon employed professional resurrectionists around 1789. A student graduated from Aberdeen and went to London to work.

“He basically said as difficult as it is in London to get bodies, in Aberdeen it’s easy. Nobody is watching the churchyards, you should go and do it. They were encouraged to do it. They had to. There was no other choice to get bodies.”

The situation was resolved barely months after the Aberdeen riot with the Anatomy Act of 1832 which brought in a legal and controlled supply of bodies for medical research, bringing the dark age of the body snatchers to an end.

It was about three years later that Dr Moir returned to Aberdeen and started a new, brighter chapter in his life.

Dr Brown said: “He is able to come back to Aberdeen in triumph, invited to be the first lecturer in anatomy at King’s.

“This is the thing. Andrew Moir was not a villain. He really believed the only way to learn anatomy was to acquire bodies. He says of medicine, in his own diary, that: ‘Medicine should breathe benevolence to all mankind’.

“So he comes back, but in 1844 he dies of typhoid fever which he caught from one of his poor patients. Doctors in those days, if they were going to be a GP, would have lots of rich, private patients, but not Andrew Moir. He worked in the dispensary, he paid for drugs for his poor patients. Here he is doing what he believes to be the right thing and ends up dying.

“He was a noble person, of noble ideals but in a situation where the actions of other people made his job nigh impossible.”

“It is a sad story, but ultimately, he triumphs. That’s why we have the medical school we have now because folk like Andrew Moir sacrificed their reputation for medical advances.”