A Highlander who played a key role in the French Revolution is to be celebrated at a special symposium in France – and also online – in December.

According to the symposium’s organisers “it would certainly be no exaggeration to assert that no other Scot exercised as much influence on events in France in the second half of the 18th Century” – and yet, in Scotland, Cuthbert of Castlehill is almost completely forgotten.

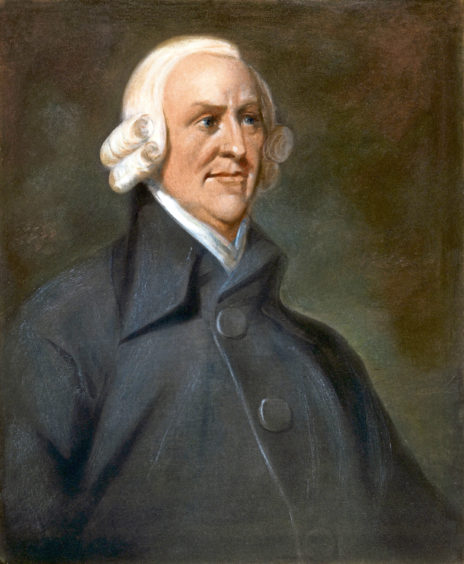

The symposium is the result of hard work by two scholars, who have sought to rediscover the details of Cuthbert of Castlehill’s unusual life. Alain Alcouffe, emeritus professor of economics at the Universite Toulouse Capitole, came across Castlehill when researching Adam Smith, the Scottish economist known as “the father of capitalism”.

Adam Smith had spent time with Castlehill in France – in fact, it was at Castlehill’s house that Smith began to write his best-known work, The Wealth Of Nations.

At the time, Cuthbert of Castlehill was already established in France, where he had, unusually for a foreigner, been promoted into the high ranks of the French Church. Castlehill kept up his links with Scotland though, and welcomed meetings with fellow Scots – in the salons of Paris, Castlehill had met and become friends with David Hume, leading philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment, and Hume had then introduced him to Adam Smith.

Intrigued by the glimpses of Castlehill’s life that were starting to emerge, Professor Alcouffe found that virtually the only brief biography of Cuthbert of Castlehill was a thesis from Bristol University, written in the 1980s by a mature student called Andrew Moore. Moore is now also involved in the symposium organisation, which for him is the culmination of a lifelong fascination with Castlehill.

Andrew Moore had enrolled in the University of Bristol in a “life-break”, to pursue his passion for history and explore his joint French-English roots. On a visit to his family in France, Moore visited a small local archive, searching for inspiration.

“I remember a large, well-lit, dusty room filled with desks and tables,” Moore recalled. “A smattering of people sat quietly in the heat, intent on books and folders of documents.”

Moore began to explain why he was there to the librarian at the front desk, saying that he particularly wanted to study the revolutionary years in France. “At this point I heard someone speak up behind me – it was an elderly nun, looking up from a pile of documents. ‘You should look into the Bishop of Rodez,’ she said. ‘Strangely, he was a Scot, a very interesting man, but little is known about him.’”

Andrew Moore rented a studio in France for a month so that he could visit the archives daily. “I have rarely been happier than for those few weeks,” he said.

He typed up his dissertation on an old typewriter, and was finally awarded a First Class Honours degree. However, despite his continuing interest in Castlehill, Moore was unable to finance further study.

Cuthbert of Castlehill remained in obscurity until Professor Alcouffe took up the baton – and now, with the upcoming symposium, interest is starting to grow, with attendees from the Sorbonne, Cambridge University, Tokyo, the US and more. Interest from Scotland, however, remained slim – until I got involved earlier this year. I write about history through biography, with a focus on my home in the north of Scotland, and I was initially interested in the Cuthbert family’s Jacobite links.

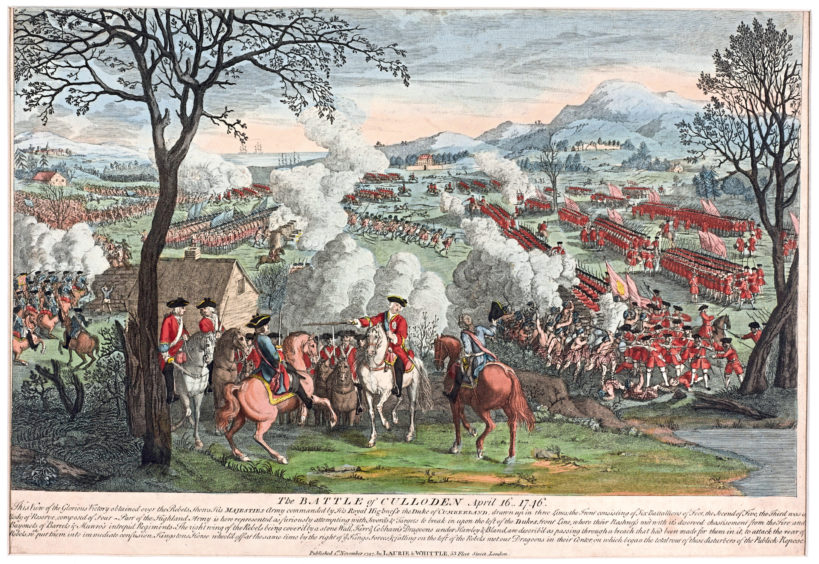

Cuthbert grew up in Castlehill House, on the road between Inverness and Culloden. His father was Sheriff-Substitute of Inverness – second-in-command to Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, the notorious Old Fox. The family were well-off – but the Battle of Culloden changed everything for them.

As the Jacobite troops retreated north to Inverness in 1746, Bonnie Prince Charlie stayed at Castlehill with the Cuthberts. Castlehill’s uncle fought alongside the prince at Culloden, but was taken prisoner after the disastrous defeat. Although the Cuthberts, like many families, had tried to walk the line between supporting the Jacobites and the government, after the battle government troops ransacked Castlehill House and destroyed part of the surrounding estate.

Financial troubles then came to a head when Castlehill’s father died suddenly, in a fall from a horse. Fortunately, Castlehill’s formidable grandmother, Jean Hay, was there to take control. She carried Cuthbert of Castlehill and his brother off to London, where she had family.

In between petitioning the government for compensation for the destruction of Castlehill House and lands, Jean Hay found positions for her two grandsons – Lewis was sent to go into business in Jamaica, and Cuthbert of Castlehill was sent to France.

The Cuthberts of Castlehill had a long, if tenuous connection with France. Almost 100 years previously, a Frenchman called Jean-Baptiste Colbert had applied to the Scottish Parliament asking for a certificate to show his relationship with the long-established and high-ranking Scottish Cuthbert family. The certificate, a Bore Brieve, would prove that Jean-Baptiste had links to nobility.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert’s family were merchants, but he became one of the Sun King’s most trusted economic advisers. The Bore Brieve gave Colbert the ticket he needed to enter the French court – and it gave the Scottish Cuthberts an entrée to French society that they had fostered ever since.

Cuthbert of Castlehill already had two uncles in France, and now he went to join them, enrolling in the Scots College in Paris to be trained as a priest.

Cuthbert of Castlehill excelled at the Scots College, particularly in languages – unsurprisingly, as he was already trilingual, speaking Gaelic, English and French. He changed his name to “Colbert”, and his skills and French connections – coupled what was apparently an appealing personality, “a becoming appearance, solid judgement and remarkable good heart” – propelled his rise in the French Church. He was made Vicaire-Generale of Toulouse, and, in 1781, in a highly unusual promotion for a foreigner, he became Bishop of Rodez.

Colbert de Castlehill, as he now was, fostered improvements in areas as varied as education, agriculture, midwifery and the road network, and encouraged the teaching and practice of new scientific theories – even sponsoring a balloon ascension.

He served on administrative committees looking at things like taxation, which led to his presence at the crucial 1789 meeting of the Estates General in Versailles. The meeting had been called to address the economic crisis – but instead, deputies drew up a long list of grievances and called for sweeping political and social reform.

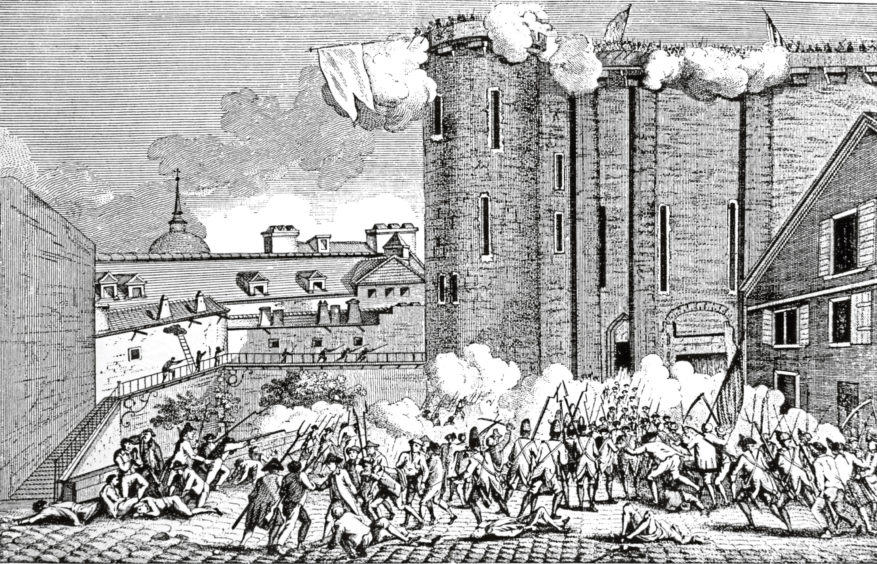

The clergy and nobility generally supported whatever the king wanted, but Castlehill unexpectedly split with the majority of his colleagues in the Church to vote along with the “Third Estate” (the general populace). Afterwards, he was carried around Versailles by a cheering crowd. “The Revolution was no doubt inevitable,” says Andrew Moore – but Colbert’s vote was a key tipping point. The storming of the Bastille took place less than a month later.

Although Castlehill believed that reform was needed, events ultimately went too far and too fast for him. He wrote to his colleagues stressing “above all his desire to avoid any conflict or violence”. And, as the Revolutionary cry that “all men are born equal” was taken up by slaves in the French colonies and contributed to the Haitian revolution, Colbert de Castlehill’s support of the Third Estate brought him into conflict with his Scottish family – his brother Lewis had become a slave owner and slave trader in Jamaica.

At the same time that Colbert de Castlehill was supporting change and greater equality in France, Lewis Cuthbert was arguing for the status quo, presenting evidence to a House of Lords enquiry where he argued in favour of keeping the slave trade.

However, when Colbert de Castlehill eventually left France he went straight to his brother’s house in London. It was a strange sort of exile – unlike other fleeing Frenchmen, Castlehill was actually returning to his home country, and to his welcoming family.

He made several return trips to Inverness. “I was enchanted to see Scotland again,” he said, “especially the place of my birth. I found, it is true, things very small in comparison with the images that I had in my head: but my heart had lost nothing there and all my affections were rediscovered, on seeing what I had left, 45 years ago.”

The organisers of December’s symposium hope that the event will lead to a reassessment of an extraordinary figure who is “much more complex” than any short account of his life can suggest. Contributions to the symposium are greatly expanding the knowledge of Colbert of Castlehill’s life, and will hopefully lead to his true place in Scottish and French history being reassessed.

More on writer Jennifer Morag Henderson can be found on her website www.jennifermoraghenderson.com Her research on Colbert of Castlehill is supported by the Highland Archive Centre (where she is an accredited researcher), by the Saltire Society, and by the Institut Français d’Écosse.