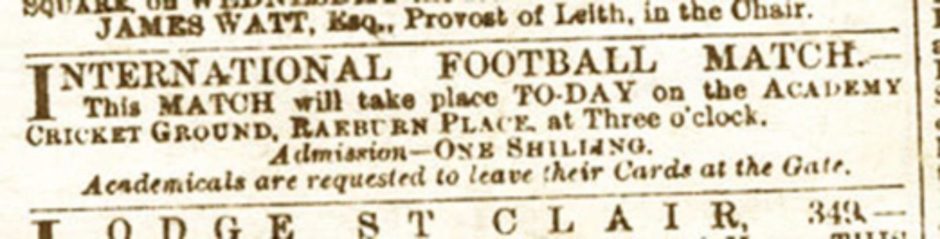

It was a low-key start to a global phenomenon: a small advertisement in The Scotsman on March 27 1871, promoting an “International Football Match”.

The message added: “This will take place [today] on the Academy Cricket Ground at Raeburn Place at Three o’clock. Admission – One Shilling.”

Eagle-eyed readers may discern that these words mention two different sports, but the occasion in question was actually the first-ever international rugby fixture between Scotland and England at the home of Edinburgh Academicals.

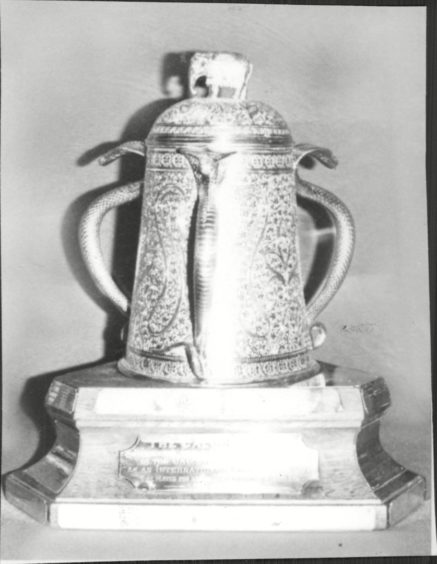

Yet although this was a hastily-organised affair on a Monday afternoon in a pursuit where the laws had still to be fully clarified – and the Calcutta Cup would not become a prized trophy for another eight years – there was sufficient interest in the meeting between these teams that 4,000 supporters flocked along to view the proceedings.

They were treated to a rousing display and a home victory even if the spectacle bore little relation to what will be served up when the same opponents lock horns on Saturday at Twickenham in the Six Nations Championship.

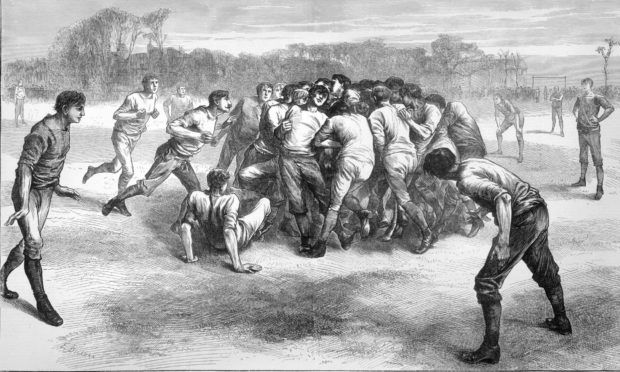

Hacking was allowed in the early days of rugby

This was in a period when there were 20 players on both sides and the idea of individuals working to pierce rival defences with attacking flair was unknown.

Indeed, scoring a try counted for nothing in itself and simply allowed the scorers to take a kick at goal.

As one historian observed: “Penalties meanwhile, were unknown, since no gentleman would ever cheat. And given the persistent bickering over the laws, it is a safe bet that few of the spectators would have been entirely clear about the rules.”

There was no grand preparation either.

The English collective, who were drawn from different parts of the country, had travelled up to Scotland the previous night on a third-class train carriage with tickets they had paid for themselves.

Their Scottish counterparts, meanwhile, were hailed from Glasgow and Edinburgh, St Andrews and Argyll and Bute, although the sport’s growing appeal ensured there were already club organisations springing up in the Borders and the north of the country.

But at this stage, 150 years ago, it all sounds closer to a riot than a recreation. The majority of the participants were concentrated in and around the scrum, with many contests dominated by ferocious and often indiscriminate mauling.

Fisticuffs often broke out – and private feuds would regularly be sorted out behind the clubhouse later on – while ‘hacking’, the deliberate tripping of an opponent who did not have the ball, was permitted until the early part of the 1870s.

The umpires had a peculiar interpretation of the rules

The game, which was played over two halves of 50 minutes, was a relentless war of attrition, but the Scots scored a goal with a successful conversion kick after seemingly grounding the ball over the line – which permitted them to ‘try’ to kick a goal.

Both sides achieved a further ‘try’ apiece, but failed to convert them into goals, as their kicks were unsuccessful and so it was that the home side eventually triumphed – by 1-0 – with Inverary-born Angus Buchanan staking a claim to fame in the chronicles by becoming the first person to score a try in international rugby.

His achievement didn’t pass without controversy and the sort of officialdom which sounds like it belongs more in Dad’s Army than a major sporting encounter.

The English had argued passionately that the crucial try should not stand, but it was awarded by one of the two umpires, Dr Hely Hutchison Almond, who refused to enter into any discussion and reached his verdict from a rather extraordinary perspective.

As he later said: “Let me make a confession: I do not know whether the decision which gave Scotland the try from which the winning goal was kicked was correct.

“But, when an umpire is in any doubt, I think he is justified in deciding against the side which makes the most noise. They are probably in the wrong.”

How the game was perceived by the press….

The next day’s edition of the Glasgow Herald told its readers in flowery language that a “fine time had been had by all”, though that probably didn’t apply to the losers.

It added: “The competitors were dressed in appropriate costume, the English wearing a white jersey, ornamented by a red rose, and the Scotch a brown jersey, with a thistle.

“The difference between the two teams was very marked, the English being of a much heavier and stronger build compared to their opponents.”

However, to the home fans’ delight, the English failed to score during the first 50 minutes, and after the teams had changed ends, the Scots began to dominate.

As regards the controversial try, some accounts suggested that the home contingent had barged their way over the line, whereas others, including The Telegraph, insisted that a player had fumbled the ball, which was a foul in England but not in Scotland.

If it sounds like a shambles, that’s probably not far from the truth. But the precedent had been set, the game later split into two distinct codes – rugby union and rugby league – and the rivalry between the Auld Enemies had continued ever since.

….and how it has a link to Harry Potter and JK Rowling

It’s difficult to believe there might be any link between that inaugural international free-for-all in Edinburgh and the arcane world of Harry Potter.

But Angus Buchanan, the try-scoring history-maker, who died in 1927, has gained posthumous recognition after being granted his own incarnation on the Pottermore site created by best-selling author JK Rowling.

The writer claimed that, ever since the 19th century, the worldwide wizarding community has thrown its support behind the Scottish rugby team.

And, in a work in 2014, she related the activities of the “squib” – “a wizard-born child with no magical powers” – Angus Buchanan, who was born in the mid-19th century, before being cast out at the age of 11 by his family.

Described by Rowling as being “large, strong and fast”, he took up rugby, and ended up playing for Scotland in the first-ever international rugby match.

The author famously wrote her early drafts of the first Potter book in different parts of Edinburgh, including Stockbridge.

And, in 1871, the history books recount that, following the Scots’ victory at Raeburn Place: “Afterwards, the ball was exhibited in a shop window in Stockbridge, a symbol of Caledonian pride at a time when the newspapers were debating the prospects for Scottish home rule.”

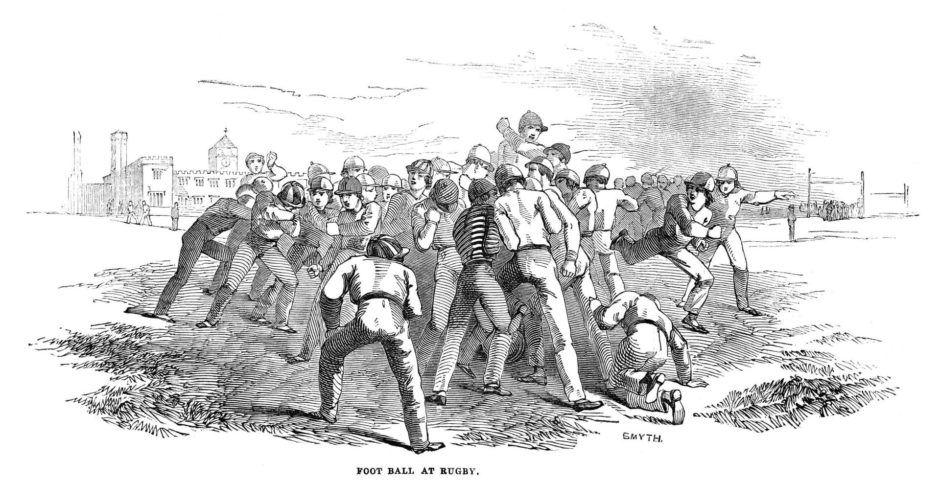

Just in case you thought 20-a-side was excessive!

JK Rowling isn’t the only famous writer with a link to Scottish rugby.

In 1815, Sir Walter Scott, the author of Ivanhoe and the Heart of Midlothian, amongst other novels, was the guiding light for a match between teams described as the men of Selkirk, with assistance from Gala and Hawick, and the men of the Valleys.

The contest, in the meadow lying between the Yarrow and Ettrick waters, was staged in front of the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch and featured up to 750 players on a field which was one mile long by three-quarters wide, ensuring that the proceedings were far more like a battle than a mere sports event.

That much was obvious when one of the players, William Riddell, a terrific athlete, broke away from the scrum and would surely have scored….but for the slight problem of being impeded by a mounted spectator when trying to finish off the attack.

The modern rugby professionals don’t know how lucky they are!