They were strange, terrifying days in Germany in the 1930s, especially for a young Scottish woman engaged to a handsome German doctor.

On declaration of war on September 1939, Margaret Dowie found herself incarcerated as an enemy alien, a possible spy, a possible Jew- and her plans to wed Dr Karl Schreck thwarted at every turn by the authorities.

What’s a girl to do?

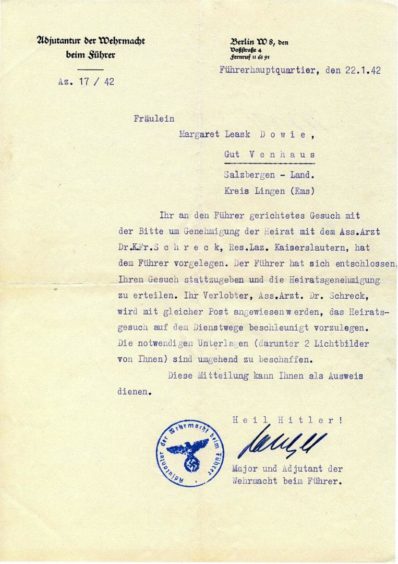

One as determined and spirited as Margaret decided to appeal directly to Hitler and wrote to him in December 1941.

To her- and Karl’s- complete astonishment, a letter arrived from Hitler’s headquarters dated January 22 1942 with extraordinary tidings.

Hitler had read Margaret’s letter and decided to grant the couple a licence to marry.

“Your application to the Führer with a request for permission to marry the Assistant Dr, Dr. K. Fr. Schreck, Reserve Hospital Kaiserslautern, has been presented to the Führer. The Führer has decided to grant permission for your request and to impart the licence to marry. Your fiancé, Assistant Doctor, Dr. Schreck will be instructed by the same post to submit an expeditious official request. The necessary documents (including 2 photos of yourself) must be sent immediately. This document can be used by you as a form of identification. Heil Hitler!”

“Perhaps this was the most benevolent action the Führer had ever taken” writes Caroline Bergius, author of The Silent Sentinels of Stürlack, in which she describes the adventures of her aunt Margaret Dowie and her mother Marion in Germany before the war and beyond.

Caroline has delved into an extraordinary period in her family’s history from 1929 to the 1980s forensically researching the story of Margaret and Marion’s innocent days in Germany before the war, and the devastating consequences for Margaret of the war and its terrible aftermath.

So how did two girls from a Glasgow family not particularly given to travelling abroad become so deeply connected with Germany in the pre-war years?

Mother answers an advert

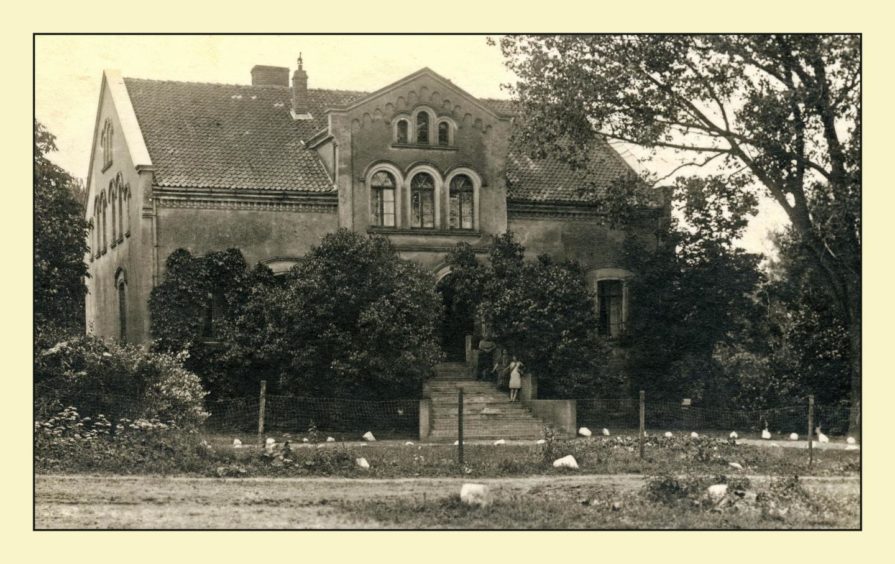

It rested on a fateful decision by their mother Maggie in 1928 to answer an advert in The Glasgow Herald in which the owner of a stately manor house farm in East Prussia was looking for a suitable English-speaking companion for her 15 year old daughter Ursula.

Margaret, then aged 19, was chosen to apply, was selected by the Cunitz family and spent the summer of 1929 in the stately but welcoming surroundings of Adlig Stürlack manor house farm, Masuria, East Prussia.

Margaret’s vivid letters home show a high-spirited, vivacious young woman capable of charming everyone she met and making the most of every minute of her adventure.

She becomes very fond of Frau Cunitz, her host, impressed by her kindness and beauty.

“When she is eating, she looks rather like a chick picking up crumbs. It is rather nice.”

Bravery in World War One

Margaret also finds out that in World War One, Frau Cunitz won an Iron Cross for her bravery.

“She stayed here on the farm while her husband was at the war and at the age of twenty-two ran the whole place with the aid of twenty-five Russian prisoners of war and one keeper who stood over them with a gun.

“After the war the Russians as a parting act set fire to three farms and they were completely burnt.”

The Great War was discussed around Margaret, who wrote: “I notice the Germans show no sense of guilt.

“They consider it was a war of defence on their part & that they were forced into it by the other countries.

“In school we are taught that Germany caused the war and in school they are taught that Russia caused the war.

“I ventured once, with some temerity, to suggest that it was a queer way to defend themselves from Russia to attack France through Belgium; but sometimes I think that the truth of the matter is that all the countries were to blame.

“Certainly now in Germany there is a genuine horror of war.

“Here in East Prussia they had dreadful experiences and most of the boys and girls are stunted in their growth as a result.”

Little did Margaret know that her words presaged even more horror and the eventual destruction of the farm some 15 years later.

German boys failed to impress

Meanwhile she seems unimpressed by German boys.

“Need I tell you that the German boys look dull and thick-skinned, and that the girls are almost unbelievably saucy.”

She recounts a whirl of social engagements in which she’s obviously a big hit, so much so that her father Peter appears concerned.

But Margaret responds: “Dad need not worry about my head being turned. As far as I am aware I am still the same girl as I have always been.”

Margaret returned home to study at Glasgow University where she graduated with an MA in English Literature in 1931.

She became a librarian, and won various scholarships enabling her to travel to Heidelberg, Prague and Florence.

Marion’s turn to visit

In the interim, in 1934, it was Margaret’s sister Marion’s turn to spend a summer with the Cunitz family.

Caroline describes the unsettling political atmosphere into which her grandmother Maggie sent her mother Marion.

“Had The Glasgow Herald failed to report the full details of political change of policy in the so-called Reich or had my grandmother simply struck up such a good friendship with Frau Cunitz in the interim, and had such confidence in her, that she had no fears for Marion’s safety?”

In the spring of 1933 members of the SA (Sturmabteilung or Assault Division of the Nazi Party) began terrorising Jewish shop-owners in the area.

“Thus intimidated, many Jewish merchants saw the necessity of deserting their properties and emigrating to Palestine, England or America.

“The fate of those who sought refuge with relatives in Berlin or even decided to await better times in East Prussia was horrifyingly revealed only a few years later to mankind.”

Fortunately Marion sailed through unscathed, her letters documented in Caroline’s book.

Fateful family holiday

None of this stopped the Dowie family from holidaying in Mittenwald in the Bavarian Alps two years later.

Margaret decided to stay on and here fate stepped in.

A handsome young doctor was also staying in her guest house in the Austrian Tyrol- Karl Schreck of Kaiserslautern.

The two got on like a house on fire.

Caroline says: “He was inebriated by her joie de vivre and she by his infectious sense of humour – so much so that they vowed to meet up again in the same venue in Austria in August of the following year, 1939.

“Considering the fact that Austria had already been annexed by Nazi Germany in March 1938 and Hitler had brazenly invaded Czechoslovakia in March 1939 occupying Bohemia and declaring Slovakia a protectorate, this was a brave plan to fulfil.”

But it went ahead, and the couple were able to enjoy an idyllic few days together in August before Karl was summoned back to his post as junior doctor in Kaiserslautern hospital.

Engagement

The two were now inseparable and planned to get engaged.

Things rapidly got complicated.

Karl realised that Margaret had to be housed in a safe place, and sent her to au pair with an aristocratic Prussian family, the von Geschers, with ‘safe’ political leanings.

At Gut Venhaus near Lingen in Lower Saxony, Margaret was placed as English tutor to the three children.

On September 1st, the British Embassy appealed to all British citizens to leave for their homeland by the last available train, departing the next day.

Needless to say, Margaret wasn’t on it.

War declared on September 3

Little did she know she would now be incarcerated in her newly acquired aristocratic domicile for a further two years and nine months.

The couple forged on with their plans to marry, but Margaret was persona non grata – and suspected as a possible spy.

She had to give up her British passport and apply for German nationality.

This process threw up a potentially lethal problem- the lengthy paperwork revealed that she had a brother named David, and to Nazi eyes this meant she might have Jewish ancestry.

A lengthy process ensured to get church records of all four of her grandparents, including her maternal grandmother, Margaret Leask of Burra Isle in Shetland.

In her book, Caroline reproduces many of the letters between Margaret and Karl and their families as her enforced detention unfolded.

Life grew ever more terrifying to the extent that in August 1941 Karl’s parents’ flat was bombed.

Gestapo interrogation

Then Margaret was interrogated by the Gestapo for clandestinely tuning into the BBC- betrayed by someone in the Gut Venhaus household.

The terrifying experience ended with Margaret getting a severe reprimand for her grave misdeed- and even the exuberant Margaret declined into a state of apathy after this.

Her spirits must have lifted in November 1941 when proof of her Aryan heritage finally arrived with Karl- but local officialdom continued to procrastinate.

Margaret writes to Hitler

In desperation Margaret took it upon herself to write to Hitler personally.

She writes to Karl: “Don’t laugh at my naiveté; but I have actually written to the Führer himself and with wildly beating heart, posted the letter in Lingen this morning.

“If you would like it, I can send you a copy.

“You can well imagine how difficult the draft was to formulate, and I don’t know what you will think about it. I at least needed to have sent it away before telling you.

“Although it would be foolish to attach any hopes to this, it was definitely a grand moment to have written to the Führer.

“And if you continue to laugh at me, the best reason for the letter is that I have undertaken everything humanly possible.

“I have had to fight fiercely for my bridegroom.”

Karl wrote back with a gentle reproach saying she should have consulted him first, and that the letter, although touching, “will not obtain its objective.”

He endeavoured to get a position for Margaret in his hospital in Kaiserslautern, now overflowing with wounded soldiers from the Western Front.

Permission arrives

Amid bureaucratic delays regarding Margaret’s post, the permission from Hitler arrived in January and an elated Margaret left her detention in the by now quite hostile surroundings of Gut Venhaus while Karl found a home for them in Kaiserslautern.

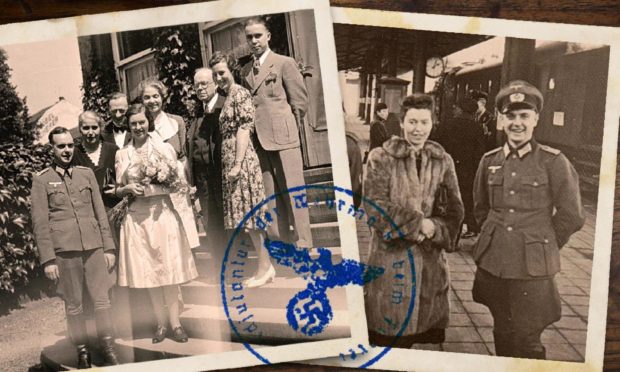

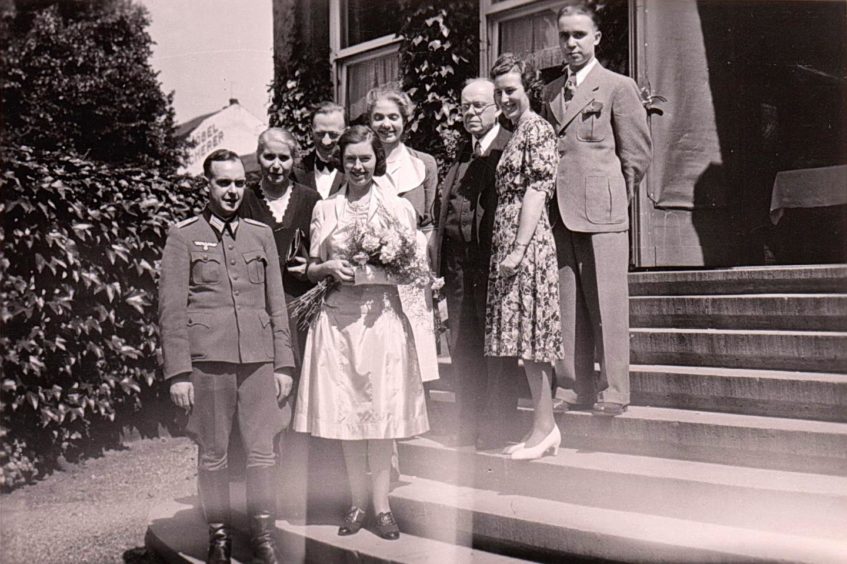

On August 1, 1942- Margaret’s 33rd birthday- Karl and Margaret got married.

A leather-bound copy of Mein Kampf, signed illegibly by the registry officer, was presented to the newly-weds- and to this day remains unopened.

After a brief honeymoon and only a week together in their new home, Karl was summoned to join an army regiment on the Russian Eastern front.

Margaret soon found herself coping with war-wounded soldiers on over-filled wards.

In July 1943 the couple were reunited for two weeks before Karl had to return to his regiment and face the horrors of the advancing Red Army.

Margaret resumed work at the hospital, but the strains took their toll and she had a miscarriage in the autumn.

Early in 1944 came news of the death of Karl’s mother and he was granted compassionate leave in March to return to the parental home, where Margaret was allowed to be with him.

Final parting

Their parting this time was the last Margaret would see of him.

By late 1944 Karl’s whole division was proclaimed lost, presumed dead.

Caroline writes: “Very probably he was a victim of the Belorussian Offensive, a massive Soviet attack codenamed Operation Bagration that began on 22nd June 1944 in the area of Minsk.

“The German Army Group Centre consisting of 800,000 men were grossly outnumbered by 2.3 million Russian troops. In the ensuing battle for the capital of Belarus and the liberation of Vitebsk, some 100,000 Germans had been encircled and trapped.

“By the end of August 1944 the Red Army announced 180,000 dead and missing; the German toll exceeded 400,000.”

The harrowing fate of Adlig Stürlack and its people is described in detail in Caroline’s book after decades-long research.

Margaret finds love again

Margaret’s extraordinary story continued in the hardships of post-war Germany, but she found love again in 1946 with a young Serb, Nikola Mitić.

They married on July 25 1951 in Glasgow University Memorial Chapel.

Meanwhile, Caroline’s parents, Marion and Richard Butcher, retired to Strathglass, near Beauly in the Highlands, and after Nikola’s death in 1967, Margaret also came north, building a house in Bishop Kinkell near Conon Bridge.

She died in a nursing home in Surrey in 1995.

Caroline writes: “There can unfortunately be no happy end to this story, but the hope remains that after all the turbulent happenings that have taken place over past centuries on Stürlack’s seemingly innocent pastures, the peace that has reigned here for over 70 years may long continue.

“Several questions, however, remain unanswered:

“Why did Else Cunitz choose to advertise in the Glasgow Herald?

“What was Karl’s fate at the end of June 1944 in White Russia?

“Was he killed outright or maybe deported to Siberia?

“How could it be that at least 100,000 German soldiers remained unaccounted for?”

Classical musician Caroline has kept the family’s German connections alive by marrying cellist Wolfgang Bergius.

The two are based in Bavaria but spend as much time as possible in Strathglass.

For more than 30 years she has been giving chamber music classes for young instrumentalists between the ages of six and 20 in Germany and on the island of Berneray in the Outer Hebrides.

The Silent Sentinels of Stürlack can be ordered through any book shop or online.