When the Olympic Games begin in Tokyo this month, they will feature in excess of 11,000 participants from 200-plus countries, battling for more than 1,000 medals in 33 different sports.

The eyes of the world will be focused on an extravaganza that was delayed due to the Covid pandemic in 2020 but which is being staged this year despite concerns from many Japanese people about the rationale for them taking place with the virus still rampant in large parts of the globe.

However, the IOC seems determined to proceed with these Games without frontiers and the BBC is committed to broadcasting up to 350 hours of coverage from the myriad venues hosting competitions.

It’s a juggernaut, a vast commercial enterprise, a sponsors’ paradise – and an opportunity for those who collect medals to have their lives transformed.

It was so, so different in 1896

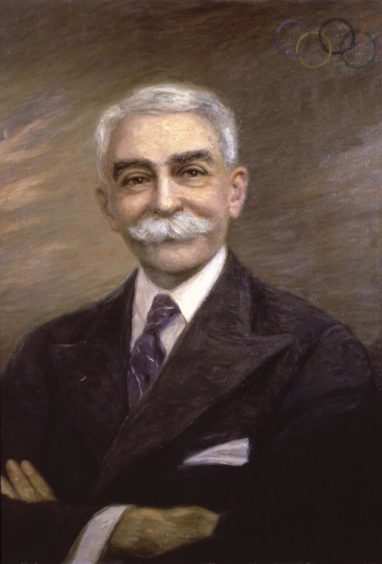

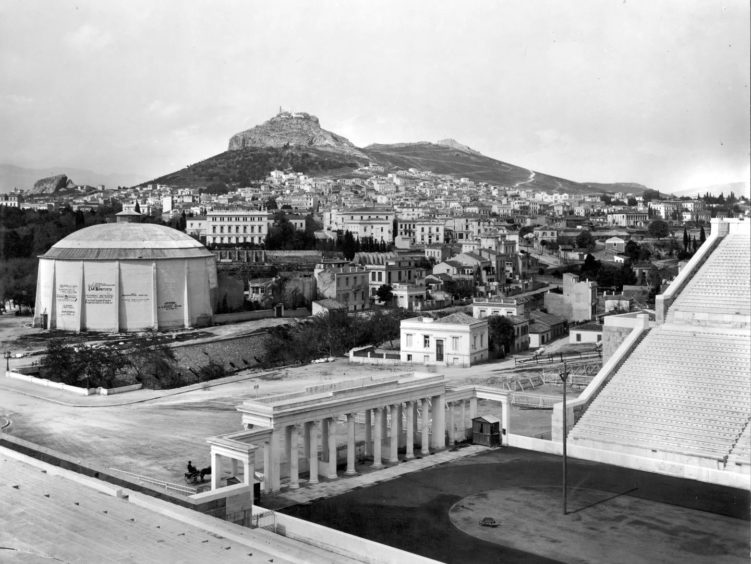

What a contrast that represents from the slapdash fashion in which the Modern Olympics were revived in Athens back in 1896, largely through the drive and enthusiasm of young French nobleman Baron Pierre de Coubertin.

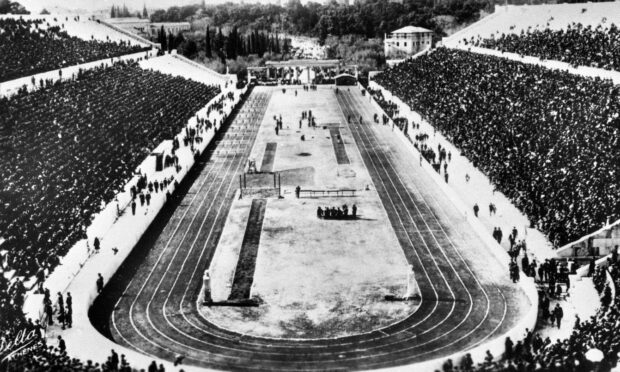

In Athens 125 years ago, 280 participants from 13 nations competed in 43 events, covering track and field athletics, swimming, gymnastics, cycling, wrestling, weightlifting, fencing, shooting, and tennis.

All the participants were men, and a few of the entrants were tourists who simply stumbled upon the Games while they were on holiday in Greece and were allowed to sign up at the eleventh hour.

The idea of them preparing for action at elite training camps would have seemed laughable.

Yet while these early Olympics featured amateur athletes, that didn’t mean there weren’t performances that merited plaudits and praise.

And, in the years between 1896 and 1912, several stalwart figures from the north and north-east of Scotland were among the champions on the medal podium.

Angus Gillan was a trailblazer

Just consider the likes of Aberdeen-born Angus Gillan, who was one of Scotland’s early stars after the rebirth of the Olympics, and won gold medals at the 1908 and 1912 Games in London and Stockholm.

An important political figure in the development of the Commonwealth and, as an administrator, one of the leading organisers of the 1948 Olympics, Gillan was an incredibly resilient character who always pushed himself to the nth degree and believed that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

He was a leading figure in the Boat Race and at Henley Regatta on several occasions, but Gillan had other priorities in his life after securing his first gold medal in the coxless fours.

In 1909, he joined the Sudan Political Service, where he established a reputation as a masterly diplomat, but returned on leave to Blighty in 1911 and, as a member of the renowned Leander Club, was part of the crew that won the Grand Challenge Cup at Henley in 1911.

The road from Aberdeen to Australia

He was home on leave again in 1912 and became a pivotal member of the British eight that surged to glory in front of their rivals at the Games in Sweden.

There was no fuss, banner headlines or even interviews with the crew in those days and these fellows weren’t even household names in their own living rooms, but they were seriously talented and tough as teak.

Thereafter, this sturdy north-east character, who was proud of his Scottish heritage on his global travels, earned all manner of distinctions.

He was appointed a CMG (Commander of St Michael and St George) in 1935 and a KBE (Knight of the Order of the British Empire) in 1939.

He didn’t turn up in advertisements for pizza or breakfast cereals, but that didn’t lessen his desire or determination whenever he climbed into a boat.

Then, after the Second World War, Gillan headed the Empire Division of the British Council and played a major part in the organisation of the 1948 Olympics in London.

The following year, he exited the Colonial Service and became the British Council representative in Australia until 1951.

Sport was in his blood throughout his existence. And it clearly had a positive benefit because he lived to the ripe old age of 95, passing away in 1981.

Just one Cornet won two golds

Others from his homeland were equally successful on the Olympic stage at the start of the 20th Century.

George Cornet is one example, a redoubtable all-round sportsman from Inverness who shone in both football and cricket and excelled in several heavy and track athletics events on the Highland Games circuit.

However, it was in water polo where he left an indelible impression when he was part of the British team that struck gold in 1908 and 1912.

Contemporary reports testify to the power of this formidable specimen; the Stockholm Games officials noted that he was 6ft 3in and weighed 15st 7lb and he brought much of his strength and athleticism to the pool.

The sport was thriving at that stage throughout Scotland and Cornet’s Inverness Amateurs team was one of the best ensembles in the country.

He also represented his homeland in the pool 17 times between 1897 and 1912 and yet the chances are that precious few people will even know his name.

He was the oldest member of the British teams that prevailed in London and Stockholm, but age didn’t prevent him from demonstrating the gifts that led one newspaper to describe him as a “veritable behemoth”.

He died in 1952, but Cornet was eventually inducted into the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame, in 2007.

He was first married to Barbara Mackintosh, who died in childbirth, after which he tied the knot with her sister, Isabella Mackintosh, and they had a daughter, Ruby.

Wally won without any scull-duggery

There were similar acts of derring-do from William Kinnear, another Olympic champion in the single sculls in 1912 and someone who was revered as the best in the world in his domain prior to the outbreak of the First World War.

Better known to his friends as Wally, Kinnear was born in Marykirk in Aberdeenshire, where he became a draper’s assistant.

He left home in 1902 for a career with the chain store Debenhams in London. Work colleagues introduced him to sculling and he became hooked on the sport.

The accomplished rower achieved the pursuit’s prestigious “triple crown” in 1911, winning the Wingfield sculls, the Diamond Challenge sculls and the Metropolitan Regatta’s London Cup.

It was nearly another century – in 2007 – before Kinnear was eventually inducted into the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame, but he was one of the highest-regarded competitors of his golden generation and he used to remark that he had derived inspiration from compatriots such as Gillan.

During the First World War, Kinnear served with the Royal Naval Air Service and then became a rowing coach. He died in 1974, aged 94.

Shaken but not stirred at the Games

De Coubertin was determined to ensure that the Olympics would be open to men of all classes, but most of the participants in these early Olympics didn’t have to worry about their financial affairs.

One of the most mercurial figures – with a link to the world’s most famous literary spy – Philip Fleming was born in Newport-on-Tay in Fife and was a dashing figure both in sport and the business world.

He was the son of Robert Fleming, a renowned merchant banker and educated at Eton and Magdalen College in Oxford.

During the First World War, he and his brother, Valentine, joined the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars, but his sibling perished on the Western Front in 1917 and was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Prior to that tragedy, Philip made an appearance for Oxford in the Boat Race in 1910, whereupon he joined Leander Club and was strokeman of the eight-strong crew that won the gold medal for Britain at the 1912 Olympics.

Fleming subsequently married Jean Hunloke, the daughter of Philip Hunloke, who had won a bronze medal in sailing at the 1908 Games in London.

But, more intriguingly, he was the uncle of Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, and his extrovert, larger-than-life persona and relish for adventure – the family built a shooting lodge at Arnisdale, near Glenelg in Inverness-shire – appealed to his younger nephew and helped inspire agent 007.

Wyndham was another casualty of war

He was the man who secured a gold medal at the 1908 Olympics, but only after a controversial disqualification of a rival, which meant he won the 400m in a race with nobody else but himself.

Confused? You should be.

Wyndham Halswelle, born in London, but from Scottish stock, which led to him being commissioned into the Highland Light Infantry in 1901, was no stranger to turbulent times, after serving in the Boer War in South Africa.

But he made history of a kind at the Games when he reached the final of the 400m with the fastest qualifying time, only to be baulked and barged by his American opponents, William Robbins and John Carpenter.

The British official, Roscoe Badger, declared the outcome as void, Carpenter was disqualified, and the race was ordered to be re-run in lanes two days later.

However, the other two US athletes were outraged at this decision and refused to take part in the rescheduled final, so a reluctant Halswelle ran on his own to collect the gold in a time of 50.2 seconds.

It is the only occasion in Olympic history where the final was a walkover and the incident soured Halswelle’s view of athletics.

He was also put under pressure from his senior officers, who felt he was being exploited, and retired after a farewell appearance at the 1908 Glasgow Rangers Sports.

He was killed at just 32, by a sniper at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in 1915.