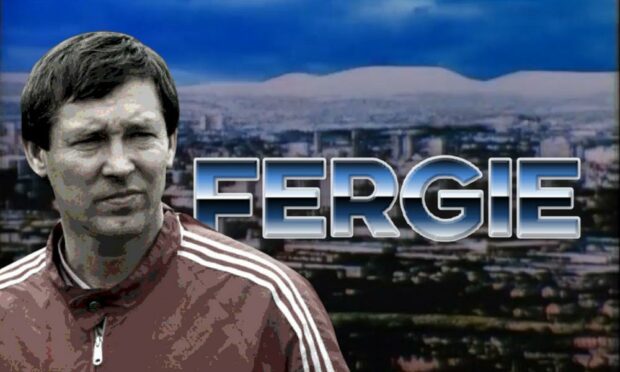

There was something truly life-affirming about Sir Alex Ferguson’s visit to Aberdeen last month to unveil a new statue of his long-term friend and fellow football legend Denis Law.

Here was the gruff managerial maestro in fine fettle back in the city where he was the catalyst for unprecedented triumphs at Pittodrie; a halcyon period in the 1980s where the Dons were feared across Europe, celebrated magnificent victories against such opponents as Real Madrid and Bayern Munich, and embodied the qualities which have defined Ferguson’s life and career.

The notion of going gently into that good night and picking up his slippers in retirement had never occurred to Ferguson before he suffered a brain haemorrhage in 2018, but that brush with death has clearly left a huge imprint on him, given the way he spoke about the experience in the documentary Never Give In, which was released earlier this year.

The former Manchester United manager even wondered “how many sunny days I would see again” as he lay in hospital and it’s little wonder he paid a warm tribute to Joshi George, the neurosurgeon who treated him.

Overcoming serious illness

Whenever one thinks of the Govan-born embodiment of Jim Taggart in a tracksuit, the conversation tends to focus on his driven, determined, occasionally dyspeptic approach to every challenge – and his hair-drier response to those who offer him less than 100% – but another side to Ferguson emerged in the aftermath of that protracted Salford hospital stay.

He recalled in the film: “There were five brain haemorrhages that day. Three died. Two survived. You know that you are lucky.

“It was a beautiful day, I remember that. I wondered how many sunny days I would ever see again. I found that difficult.”

He also had trouble speaking and the vulnerability cast a cloud over his mood, to the stage where he admitted: “I was trying to force it out, but I couldn’t get it out. One of the doctors came in and I was crying because I felt helpless.

“I would have hated to lose my memory. It would have been a terrible burden on my family, if I was sitting in the house not knowing who I am.

“I don’t remember anything. When I collapsed that Saturday morning, I have no idea what went on. People say I was sat up talking in Macclesfield Hospital before I went to Salford, but I don’t remember a thing. I am not sure, when the moment comes and you do die, whether it is the best way to go.

“The moments when you are on your own, there is that fear and loneliness that creeps into your mind. You don’t want to die. That is where I was at”.

This was unfamiliar territory for a man associated with positivity, prizes and plaudits, but Ferguson, for all the stramashes and controversies which have enveloped him throughout his 80 years, has never been a Flashman type, screaming and shouting at players just for the sake of it.

On the contrary, I remember arranging to speak with him, in the prelude to Manchester United visiting Aberdeen to participate in a testimonial match for the club’s yeoman scout, kit man and all-round Dons fanatic Teddy Scott.

I was asked to ring the United training ground at 8am, where he was already in his office, methodically, meticulously planning, plotting and preparing to the nth degree for the next Premiership tussle.

But, for the next 15 minutes, he was brilliant company while extolling the virtues of Scott, a man he praised as “a salt-of-the-earth character who would do anything for Aberdeen”.

It was a reminder of two facets of Ferguson’s nature. Firstly, that when he was growing up in the 1940s and 1950s, working-class Glasgow was defined by the shipyards, trade unionism and football on every piece of grass and ash.

Even as a youngster, his commitment to education, Old Labour principles, and forging friendships which have endured to this day, highlighted his devotion to a world that may have vanished, but to which he remains forever welded.

And secondly, that it has always been better to have him as a friend than an enemy.

Nobody who has ever crossed him, on or off the field, will disagree with that assessment of this cantankerous perfectionist, a coruscating force of nature who transformed the rag-tag United collective from being a near laughing stock in the late 1980s into arguably the most successful side which has ever paraded its powers in British football.

Was Aberdeen Alex Ferguson’s crowning glory?

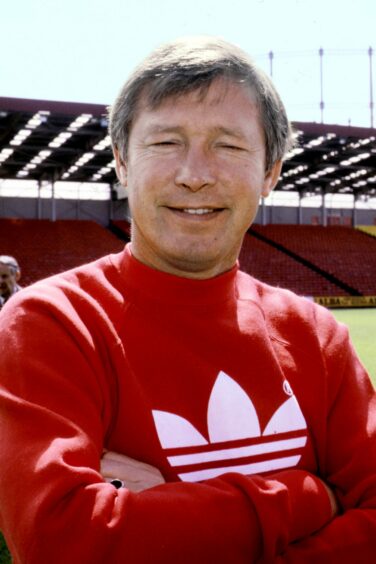

None of it has happened by accident. But if there is one message from Ferguson’s domination, whether at Aberdeen from 1979 to 1986 or in Manchester thereafter, it’s that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains, for ceaselessly raging against the dying of the light, and (adhering to Gary Player’s famous tenet) that the harder his team practiced, the luckier they got.

He recognised he was never a great footballer, but nobody could question his application or industry.

And although he suffered rejection at Rangers and witnessed the club’s worst traits in the guise of their public relations officer, Willie Allison, whom he branded a bigot, Ferguson used the indignity of leaving Ibrox to become one of the greatest managers in the sport’s history.

Whereupon, his relentless ambition yielded undreamt-of success at Aberdeen, who won the European Cup Winners’ Cup in 1983 and grew accustomed to beating both halves of the Old Firm, such was Fergie’s influence.

He could have returned to Rangers in a managerial capacity, but instead chose the bigger challenge of resuscitating a Manchester United squad who had become better known for their nightclub carousing and Bacchanalian excess than their performances on the pitch.

So he weeded out the miscreants, recruited his own personnel and, oblivious to his early travails in England, gradually, inexorably, stamped his imprimatur all over his domain.

The sceptics, led by the Milk Tray man, Alan Hansen, scoffed: “You’ll never win anything with kids“.

However, fuelled by an instinctive mistrust of people who basked in comfort zones rather than put their bodies through the wringer to make the most of their talent, he almost single-handedly dragged the English game kicking and screaming into the 21st century.

Sir Alex became a surrogate father to many

There is certainly no denying the momentous impact which he made on Old Trafford affairs for more than quarter of a century: after all, the Red Devils amassed a staggering 38 trophies, including 13 championship titles, a brace of Champions League honours and the FA Cup on five occasions.

And the youngsters regarded him as something close to a surrogate father. Just ask Cristiano Ronaldo, who returned to Old Trafford this year, because he was still in thrall to his old gaffer.

Or David Beckham – or Eric Cantona, whose career might have finished in disgrace when he attacked a fan after jumping into the crowd during a match against Crystal Palace in 1995.

But no, when he needed a public defender, a pillar of support, Ferguson was there, akin to a protective shield. One of his central tenets has always been: “At the end of the day, the bus goes on and we don’t wait for anybody”.

But sometimes, he has tolerated a player’s idiosyncrasies, as in the case of Cantona, if he considered them to possess special gifts.

All the while, Ferguson’s man-management skills were based on the same convictions that had made him such a potent shop steward in his youth. “I am careful of the players I lay into,” he once said. “Some can’t handle it. Some can’t even handle a team talk. There are some I don’t look in the eye during a team talk because I know I am putting them under pressure.”

Yet, while he may have ruled the roost in Manchester for a generation and can still be witnessed in the directors’ box at most matches, there’s a compelling argument that his greatest success came in the north-east of Scotland, where a 30-something Alex Ferguson arrived in Aberdeen like a whirling dervish.

It was in his genes, his DNA, that Aberdeen had to be better, fitter, more clinical and, ultimately, more professional, than their rivals. We’ve heard all about Alfredo Di Stefano’s praise for the Alex Ferguson-led Pittodrie organisation after the European Cup Winners Cup final in Gothenburg – “Aberdeen have what money can’t buy: a soul, a team spirit built in a family tradition” – but this family was much closer to The Sopranos than The Waltons.

And what riches this implacable clan gathered. In just seven years, there were three league titles, four Scottish Cups, a League Cup and two European baubles: the CWC, followed by fresh success against Hamburg in the final of the European Super Cup just a few days before Christmas in 1983.

Football is etched in the Alex Ferguson DNA

Bob Crampsey, the late TV pundit (and a highly intelligent scholarly figure) once talked to me about the ‘magic trick’ which Ferguson had pulled off in such a short time among the Dons. As he said: “Alex can be brusque, he can shout and scream at his players and put the fear of God into them.

“I have seen him venting his wrath at some people, then, a few minutes later, he will be chatting to them with a smile on his face or taking the trouble to phone them the next morning and say sorry if he had crossed the line.

“When it comes to winning football matches, yes, he is a very hard man. But there’s a lot more to his story than that.”

There is. And his relentless attitude is one of the reasons why Ferguson’s legacy is immense throughout Scottish, English and European football: the indefatigable insistence to be the best his teams can be, to never say die.

He has never been one of life’s sentimentalists. But sometimes, we should stop and appreciate when a special milestone is reached.

So let’s raise a Hogmanay toast to him and wish him a happy 80th birthday.

More like this:

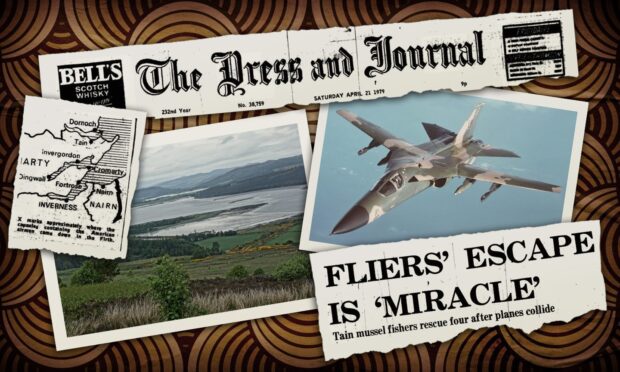

Aberdeen FC’s ’80s heroes could have lined up in Escape to Victory

When Jimmy Greaves almost played for Aberdeen under Sir Alex Ferguson

Our special comic book to celebrate Sir Alex Ferguson’s 80th birthday