He was the man who seemed intent on bringing a touch of glamour to the north east when he moved into a grand country house in 1921.

Almost everybody around Huntly and Forgue swiftly grew acquainted with the dapper toff who had made it his mission to build a grand estate in the region to equal those he already possessed in England and Ireland.

Nobody suspected there was anything amiss with Lieutenant-Colonel George Hanbury Williams, who, bold as brass, embarked on a giant spending spree throughout his months in Aberdeenshire that saw him purchasing myriad goods and services from the majority of the businesses in the area.

Yet, if it seemed too good to be true after the horrors of the First World War that this dashing veteran, a stalwart of the 13th Hussars, was intent on creating a tourist attraction that would woo visitors from all over the world and provide jobs for the locals, that’s because it was too good to be true.

Instead of bolstering the local economy, he left a massive trail of debt in his wake and was eventually unmasked as a Walter Mitty-style character who had devised several different pseudonyms and invented an entirely fictional military history, which bore no resemblance to the facts.

And, eventually, the whole façade came tumbling down like the House of Usher during a dramatic trial in Aberdeen 100 years ago this month.

The saga began at the end of 1920 when Aberdeen estate agents Reith and Anderson received a letter from Boulogne in France, ostensibly from a Lt-Col Williams, who had an outstanding war record and was seeking to purchase a grand mansion, which would host shooting parties, somewhere in the area.

He had noticed that the property of Drumblair, in the parish of Forgue, was open to offers and requested the chance to find out further details about the residence, which was owned by local farmer, Thomas William Robertson.

As the months passed, there was regular correspondence between Williams and the company and the former made several extravagant claims for himself, providing his rank, military history and expertise in the property market.

The people he defrauded included two hoteliers in Huntly and Forgue, a farmer in Forgue, two butchers, two ironmongers, a bookseller, two tailors, a draper, a motor and cycle agent, a garage keeper and a firm of motor engineers, a shoemaker, a china merchant, a baker, a photographer, and a firm of coal merchants…”

Aberdeen Journal report

At any stage, his plan might have been rumbled, but, according to the contemporary accounts in the Aberdeen Journal and other newspapers, he was a smooth talker, a convivial character, a bon vivant with a clear idea of exactly what he wanted and he made his interest in taking over a large country house seem like a normal part of his everyday existence.

Even when he arrived in the Granite City in April 1921, he impressed those he met with his enterprise and determination to construct something that would offer a lasting legacy – an estate for the ages – even after he was gone.

There was no hint during the initial meeting that Williams wasn’t a full-blooded member of the aristocracy, nor that he had concocted a vast tissue of lies about his past and present. But perhaps nobody was listening too closely.

There was certainly little indication of anybody bothering to check on his background or even going to the trouble of contacting the regiment of which he claimed to be such a prominent member.

The lies just kept on coming: he said he had been 29 years in the Royal Army, had a large pension, owned two estates in England and one in Ireland, and was married to Lady Mercer, who was connected with the Duke of Sutherland.

He had a passion for creating new developments which profited both himself and the communities in which they were based.

And he vowed to do everything to replicate in Scotland what he had done elsewhere in Britain.

It was deception on an industrial scale, gargantuan graft, but it worked.

On April 29, he persuaded bank agent Peter Cowie Ironside to enter into a verbal agreement to offer him a 10-year lease for the palatial mansion house and shootings of Drumblair at an annual rent of £350. A steal… quite literally.

In the course of these discussions, he spoke eloquently about bringing another successful project to fruition and enhancing the lives of the locals.

In reality, he had barely a cent to his name and relied on credit and his connections and credentials to perpetrate systematic fraud across the region.

Having obtained the lease from the agents, Williams took possession of the property on or around May 6 1921 and quickly got to work on a crime spree.

In the period between then and October, he induced a number of traders to deliver to him a variety of luxury goods amounting to more than £323 – the equivalent of around £15,000 in today’s money – which he had no intention of paying for or indeed had the means to do so.

As the Aberdeen Journal noted: “The people he defrauded included two hoteliers in Huntly and Forgue, a farmer in Forgue, two butchers, two ironmongers, a bookseller, two tailors, a draper, a motor and cycle agent, a garage keeper and a firm of motor engineers, a shoemaker, a china merchant, a baker, a photographer, and a firm of coal merchants, all of them in Huntly.”

It was only once several gentle requests for payment were declined and a few sterner demands for cash yielded nothing but hot air that the business owners decided to contact the police. And Williams’ world suddenly crashed to earth.

Huntly fraud court case a sensation

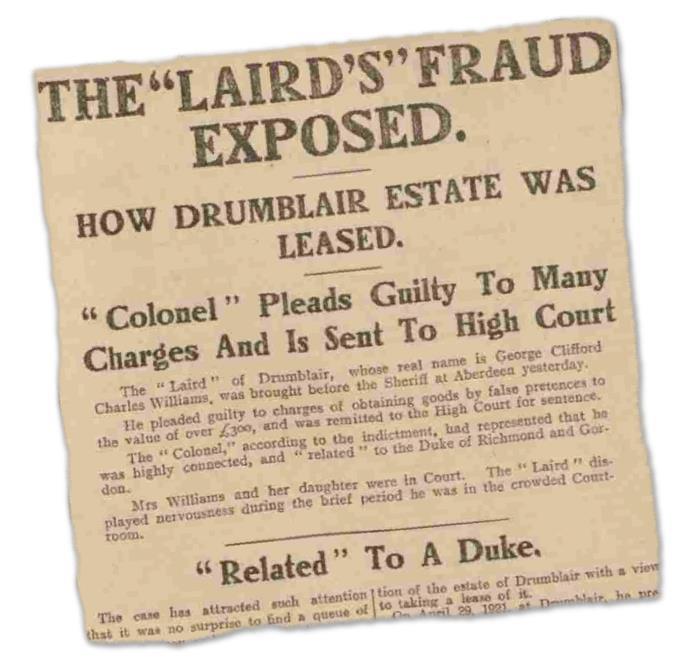

By the end of 1921, the man with many names had been charged and the details of his life were spelled out to a public which lapped up the details.

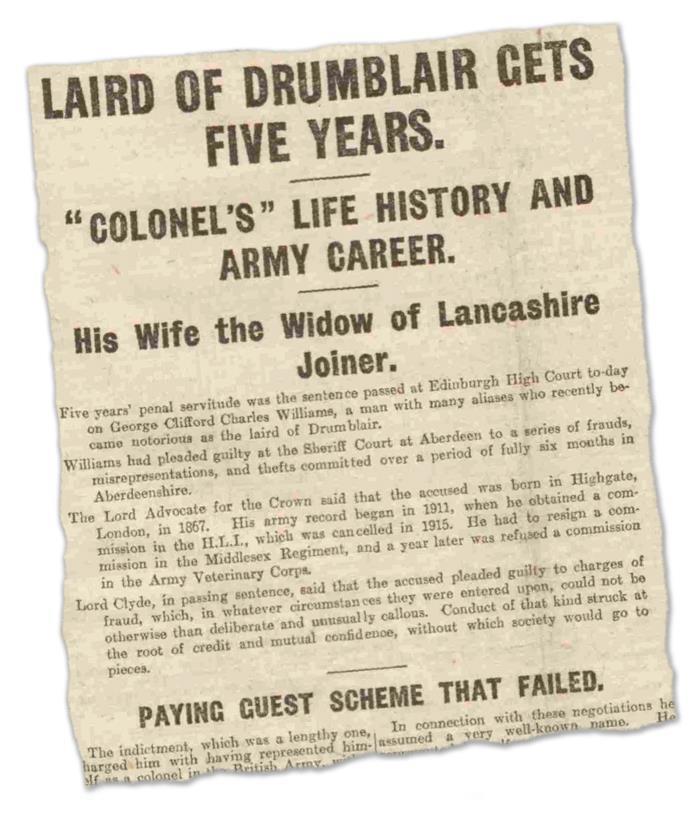

Far from being a wealthy soldier with a record of gallantry, it emerged that Williams had been born in Highgate in London in 1867 and had not joined the Army until 1911 when he obtained a commission in the Highland Light Infantry that was subsequently cancelled in 1915.

He was later forced to resign a commission in the Middlesex Regiment and, the following year, was refused a commission in the Army Veterinary Corps.

Bad news had spread about his behaviour – which mercifully, for him but not the population of Huntly and Forgue, was confined to military circles.

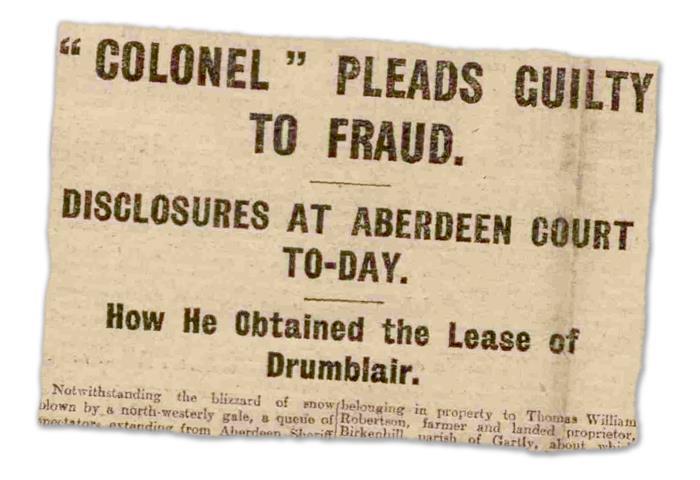

When the matter reached Aberdeen Sheriff Court, there was substantial interest in the case and the Aberdeen Journal covered it thoroughly.

But, although this was obviously a serious matter, there was still something rather hilarious about the third paragraph of their report.

This ran as follows: “The courtroom was packed when the Sheriff took his seat.

“Williams, who was charged as George Clifford Charles Williams, alias George Williams Wilson, alias Creswell Charles Claud Herbert Hawfa Williams, alias George Hanbury Williams, was brought from (the city’s) Craiginches Prison, where he has been detained, in the prison motor van.

“He entered at Lodge Walk, in front of a police constable, and looked very dejected and anything but the prim and proper county gentleman who he had represented himself to be when he arrived in the north east.

“The indictment with which he was charged comprised a formidable document of four pages of foolscap, with another three pages of a list of tradesmen whom he had defrauded last year.

“He was charged with having conceived a fraudulent scheme to get occupation and possession on a long lease of mansion house and shooting lodgings, food, clothing and other goods, which he had no intention of paying for and which he was in no position to pay for.”

He was, as a shooting enthusiast might say, bang to rights.

And after being convicted in Aberdeen, it merely remained for Williams to be sentenced.

Williams handed harsh punishment

Once again, the public turned up in copious numbers to discover his fate and discovered new information about Williams, how he had failed to make his name in the Army, had been declared bankrupt in March 1920 and was married to a Mrs Seager, the widow of a joiner from Clitheroe in Lancashire.

At no stage was any explanation given for how his bankruptcy could have been missed by the banking authorities who granted him carte blanche to purchase a handsome estate just over a year later.

The Dundee Evening Telegraph reported: “The Lord Justice-General said the charges to which the accused had pleaded guilty were not charges of having undertaken an unsuccessful commercial speculation, but charges of fraud.

“They disclosed an extensive course of fraud which was entered upon deliberately and prosecuted with unusual persistence.

“Conduct of that kind struck at the very root of credit and confidence, without which society would go to pieces, and it was conduct by Williams, moreover, which was heinous to the law.

“He could not pass a less (sic) sentence than five years’ penal servitude.”

Williams had no means of repaying the 21 tradespeople from whom he had fraudulently acquired goods during his short stay at the mansion.

As somebody who was already in his mid-50s, this was the end of the line for him and there’s no word on what happened to him after he had been incarcerated.

The Aberdeen Journal said simply: “Laird of Drumblair Gets Five Years” and detailed the ‘so-called Colonel’s life history and military career’.

But how on earth did he manage to enjoy the high life at all, even if it was only for a few months?